Australia’s new Defence White Paper has plenty to say about a ‘secure, resilient Australia’.

Paragraph 3.6 states: ‘Our interest in a secure, resilient Australia also means an Australia resilient to unexpected shocks, whether natural or man-made, and strong enough to recover quickly when the unexpected happens’.

Establishing a definition of ‘resilience,’ particularly as it applies to communities impacted by natural disasters, is a hard nut to crack. Like many trans-disciplinary concepts, its meaning and usage has been debated by many professional and regulatory groups.

The growing prevalence of official strategies, policies and published national and international guides focusing on disaster resilience highlights the significant interest in the concept, especially as it applies to disasters and their impacts on communities. Not having clarity on the underlying principles of community resilience is problematical for good policy and disaster planning practice.

We need to understand better the underlying principles of what constitute a cohesive and resilient community—and from this develop effective measures of resilience and resilient practice.

The experience of living through a disaster challenges the wellbeing and sense of safety of all those impacted and is particularly disruptive to community cohesion and viability. Those experiences are always personal and can be difficult to understand and engage with institutionally as they cut to the core of an individual’s sense of safety and profound dislocation and loss.

So while ‘community resilience’ is referred to in many reports and institutional strategies, a relevant question is whether ‘resilience’ as a practical concept is understood well enough to support and nurture its regrowth in devastated communities.

Generically, resilience can be described as the capability of an organisation or institution to withstand the impacts of disturbances (from external or internal sources) while maintaining some acceptable degree of functionality or service delivery and when able, regain any lost capacity.

While recovery is often complicated, its focus is on the return of a community to a semblance of normality. Physical damage to essential lifelines, loss of housing stock, and the difficulties caused by evacuation can all add significantly to community-wide and regional impacts.

The Australian National Strategy for Disaster Resilience (NSDR) affirms the benefit of coordinated efforts of people working together to prepare for, withstand and recover from natural disasters it also states the importance of building the resilience of our communities. Disaster mitigation includes improving the safety of community members, reducing damage to property, rapid recovery, and a reduction in overall costs to national, state and regional economies. The NSDR provides high-level policy guidance and sets a clear mandate for coordinating national thinking on readiness and resilience needs, but doesn’t establish clarity on the underlying principles of community resilience.

The need for greater detail in the definition is also an international issue. The lack of clarity on how to define and measure resilience in communities was recognised in a 2015 symposium sponsored by the US National Institute of Standards and Technology, which focused on three key gaps in official knowledge:

- The definition of measurable standards for community resilience and for essential infrastructure and buildings

- Pathways to adopting and implementing standards for resilience in communities, infrastructure and buildings

- Identification of the political, economic, and social incentives to promote investment by the public and private sectors, and individuals in supporting resilience

Useful steps have been taken in Victoria with an approach to community resilience that recognises the unique networks, connections and structures through which individuals, households and communities connect to each other and their built and natural environment. Queensland has also made great steps towards preparing for resilient outcomes by defining a range of initiatives such as the Get Ready Queensland Program.

Even with State and Federal policies and practices giving considerable attention to enhancing the response and recovery aspect of communities in need, there remains a need to establish deeper understanding of the underlying principles that make up a truly resilient community.

While many might imagine a new model I think we can safely look backwards in time, over 30 years, to seminal thinking on environmental aspects of public health (integrating social, environmental and economic factors) and to the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future (the Brundtland Report).

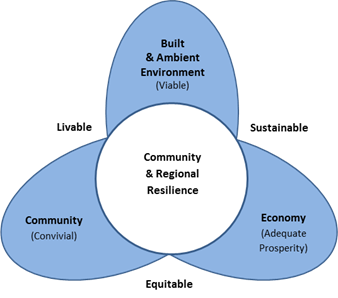

The following Figure, derived from these works, details sets of principles ideal for establishing a baseline of enabling factors active within resilient communities and their surrounding regions.

In an idealised form communities thrive when people live in viable, built and ambient environments; benefit from prosperous local and nearby economies; and participate in convivial community life. Together those principles support sustainable, livable and equitable livelihoods.

As underlying principles, those elements may be seen as both surrogate measures of ongoing community resilience and recovery targets after the impact of disasters. Those principles are key factors in renewed policy development targeting thinking about disaster resilience. They’re scalable up to State and Federal levels and may allow new and different disaster planning and prevention options to be defined. Keep a close eye on upcoming future strategy dialogues here at ASPI for further discussion on that important issue.