Before toppling Saddam Hussein in 2003, much of the west backed the Iraqi dictator during the 1980–88 war against Iran. Iraq’s Shia majority fought against their coreligionists in the Shia Islamic Republic during that war. Things started to change after the first Gulf War in 1990–91, in response to Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait. In its messy aftermath, the west encouraged Shia and Kurds to rise against Saddam, and then left them to their bloody fate. Scroll forward to 2003 and it’s unsurprising that Iraqi Shia came to place more faith in Iran than the west, and still do.

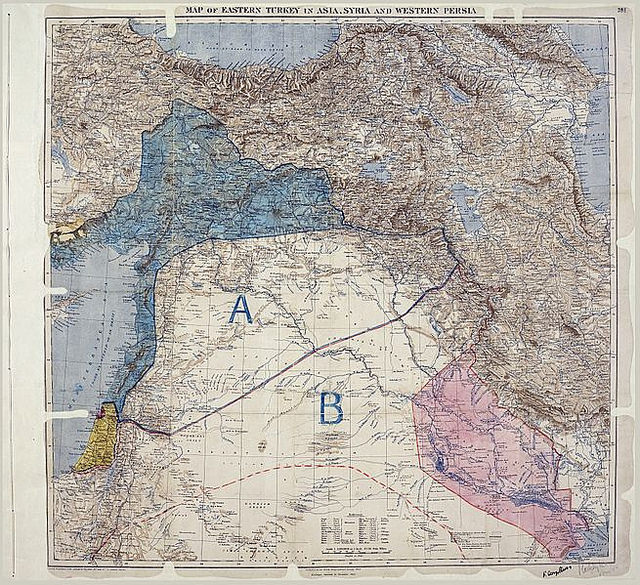

What’s happening now is a lot more than can be reasonably blamed on Sykes-Picot.

First came Lebanon, torn apart in its 1975–90 civil war whose main (if constantly shifting) battlelines were between Muslim and Christian. That was in part because of France’s 1920s move to enlarge Mount Lebanon, mainly Christian and Druze, into a Greater Lebanon which bolted on big Sunni and Shia populations. Later, within its Syria mandate from the interwar League of Nations, it tried to re-engineer Syria into a Millet-style, divide-and-rule division, including enclaves for the Druze and Alawites.

But what had been a Sunni-Shia subplot in the drama—going back to the 7th century schism in Islam—burst onto centre stage after the US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003. It was that, and not Sykes-Picot, which catapulted the Shia minority (a majority in Iraq) to power in an Arab heartland country for the first time since Saladin ended the heterodox Shia Fatimid dynasty in 1171.

That tilted the regional balance of power towards Iran: Shia, Persian and with ambitions as regional hegemon to rival Saudi Arabia as well as Israel—traditionally the two pillars of US strategy in the Middle East.

Since 2003, the overarching conflict has pitted Sunni against Shia, fuelled across the region by the inter-state rivalry between Saudi Arabia and Iran. Iran has forged a Shia axis from Baghdad to Beirut, and down into the Gulf, while Saudi Arabia and its Sunni allies, angered by US ineptitude in Iraq and reluctance to support the mainly Sunni insurgency against Bashar al-Assad in Syria, have helped contribute to the Sunni jihadism that has stepped into the vacuum.

ISIS, which competes with the Wahhabist Saudis as to who is the most implacably bigoted hammer of the Shia both condemn as heretical rafidah or rejectionists, has fanned the embers of the Sunni–Shia stand-off into border-busting, millennarian flame.

The intensity of the violence, Iraq’s and Syria’s loss of any sense of national narrative, and the collapse institutions that offer citizens a common platform, have stampeded millions into what security they can find amid sect, tribe and militia. Power is now very often local in countries partitioned by warlords, through whom even powerful external actors like the US and Russia have to operate.

When the fighting stops, and the jihadistan of ISIS is dismantled, a return to the iron centralism of the past is most unlikely. As I have argued elsewhere, some form of federalism, with securely devolved power and a loose national compact, offers probably the only way forward. The trick will be to find ways of institutionalising and broadening local power away from the warlords, making it mutually acceptable and recognisable across diverse groups, through such things as local policing to a fair share-out of national resources.

The larger Levantine canvas designed by European imperialists a century ago will probably not see any clean breaks. If some form of confederal consensus eventually emerges from the fractured chaos of the present, there will be a re-articulation of national space into more homogeneous fragments, and soft borders for, for example, the Sunni of west Iraq and east Syria, and the Kurds of the north of both countries, who for practical purposes already govern themselves.

There are no regional models for this. Lebanon, not a model anyone would emulate, was shattered into relatively homogeneous bits by the war and now limps along in the penumbra of warlords in suits. But despite 22 years of Israeli occupation ending in 2000, and 29 years of Syrian occupation that ended in 2005, the external borders have not moved one millimetre. Syria and Iraq might turn out differently.

When so many threads in such interwoven societies are pulled so hard at the same time, do they unravel or re-tangle? When Edmund Burke spoke of ‘the little platoon we belong to’ as the ‘first link in the series by which we proceed towards a love to our country’, he was reflecting on the French Revolution, relatively uncomplicated in comparison to the Levant and Mesopotamia—before or after Sykes-Picot.