Air combat capability: the good news and the bad news

Posted By Andrew Davies on October 4, 2012 @ 14:35

The Australian National Audit Office last week released a pair of related audit reports, on the acquisition of the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter [1] and the management of the current fast jet fleet [2]. The reports are worthwhile reading—not because they are sensational, but because they aren’t. The audit office has done a fine job of shedding some light into the corners of the very complex business that is managing the current air combat capability while simultaneously developing its successor. And it does so in a dispassionate and balanced way.

Not surprisingly, they find that there are some real risks emerging about the timeline for acquiring the F-35. The current plan for retiring the ‘classic’ Hornets, 71 of which form the lion’s share of the fast jet fleet, is to have them withdrawn from service in 2020. The ANAO note that the difficulties arise from a combination of development issues in the United States (over which the Australian Government has no control) and decisions made locally to delay earlier F-35 delivery intentions. Together, these make the ‘planned transition to an F‐35‐based air combat capability in the required timeframe, so that a capability gap does not arise between the withdrawal from service of the F/A‐18A/B fleet and the achievement of full operational capability for the F‐35’ a real challenge.

Not surprisingly, and like ASPI last year [3], the ANAO wanted to know what the contingency plans are. They got a partial answer:

However, in response to ANAO inquiries about contingency plans, Defence indicated that planning was underway to advise the Government on options in relation to this matter, including a limited extension beyond 2020. Nonetheless, should further delays occur in the JSF Program, Defence’s capacity to absorb any more delays in the entry into service of the replacement air combat capability to be provided by the F‐35A has limits, is likely to be costly, and has implications for capability.

One of the implications of this observation (which, to be clear, the ANAO doesn’t say, sensibly opting to remain within their terms of reference) is that any attempts to eke more ‘savings’ out of the fast jet transition by further deferring F-35 purchases would have to take into account the total cost of such a step—which would require a view beyond the four year current estimates period.

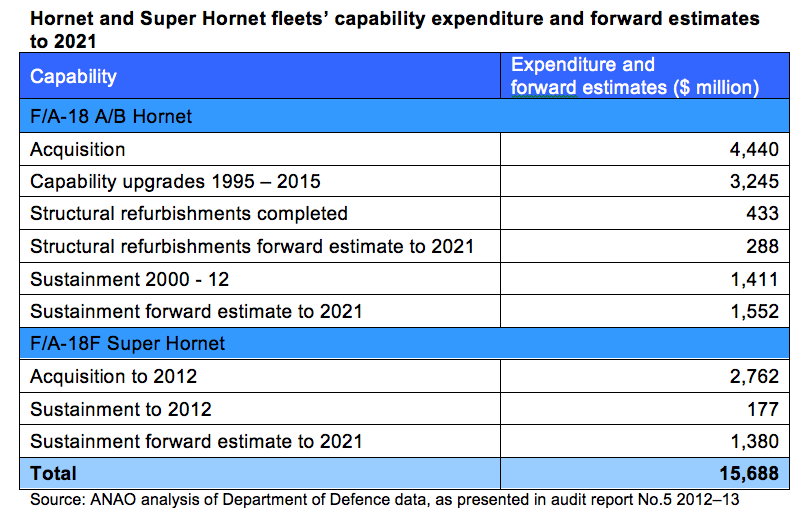

Along the way the ANAO produces some very interesting facts and figures. The table reproduced below shows an estimation of the total cost of the Hornet and Super Hornet fleets. At almost $16 billion, only $7 billion of which is acquisition cost, it shows that through-life costs, which are often relegated to a distant second place behind the ‘sticker price’ of new equipment are a substantial part of capability planning considerations.

[4]

[4]Their further breakdown of the sustainment costs for the classic Hornets show the effects of aging on running costs:

Annual spending to sustain the Hornet fleet has averaged $118 million since 2000–01, but is trending towards $170 million per annum over the next several years. The cost of airframe corrosion‐related repairs has also increased significantly, from $721 000 in 2007 to $1.367 million as estimated in 2011.

There are some real risks in keeping the ‘classics’ flying. They were designed for a 6,000 flying hour lifetime, and at current projected rates of effort will remain under that until 2020. But, ominously, the audit report notes that:

… all but nine aircraft have experienced structural fatigue above that expected for the airframe hours flown, leading the Air Combat Group to take steps to conserve the remaining fatigue life of its F/A‐18A/Bs to ensure they remain operable up to the safe life of 6000 airframe hours.

We know from experience with the F-111 fleet [5] that increasing uncertainty can arise as airframes near the end of their lives, so surprises can’t be ruled out here. It’s reassuring, then, that the ANAO found that ‘…Defence has implemented sound managerial control over the upgrade and sustainment of its F/A‐18 Hornet and Super Hornet fleets’, and that the technical airworthiness regulation model managed by the RAAF is effective.

On balance, the ANAO report shows that the margin for error in the transition from a mainly Hornet fast jet fleet to a mainly F-35 fleet has reduced to the point where any further delays will come at a significant cost and greater risk. While that’s no great surprise to those of us who have studied the subject closely, it’s a very valuable contribution to the public literature on this expensive and important national capability.

Andrew Davies [6] is senior analyst for defence capability at ASPI and executive editor of The Strategist.

Article printed from The Strategist: https://www.aspistrategist.org.au

URL to article: https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/air-combat-capability-the-good-news-and-the-bad-news/

URLs in this post:

[1] acquisition of the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter: http://www.anao.gov.au/Publications/Audit-Reports/2012-2013/F35

[2] management of the current fast jet fleet: http://www.anao.gov.au/Publications/Audit-Reports/2012-2013/F18

[3] like ASPI last year: http://www.aspi.org.au/publications/publication_details.aspx?ContentID=292

[4] Image: http://www.aspistrategist.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/Picture-20.png

[5] experience with the F-111 fleet: http://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/search/display/display.w3p;query=Id:committees%2Fcommjnt%2F9433%2F0001

[6] Andrew Davies: http://www.aspi.org.au/sitefunction/cv.aspx?sid=3

Click here to print.