This post is an excerpt from the ASPI publication ANZUS at 70: the past, present and future of the alliance, released on 18 August. Over the next few weeks,

This post is an excerpt from the ASPI publication ANZUS at 70: the past, present and future of the alliance, released on 18 August. Over the next few weeks, The Strategist

will be publishing a selection of chapters from the book.

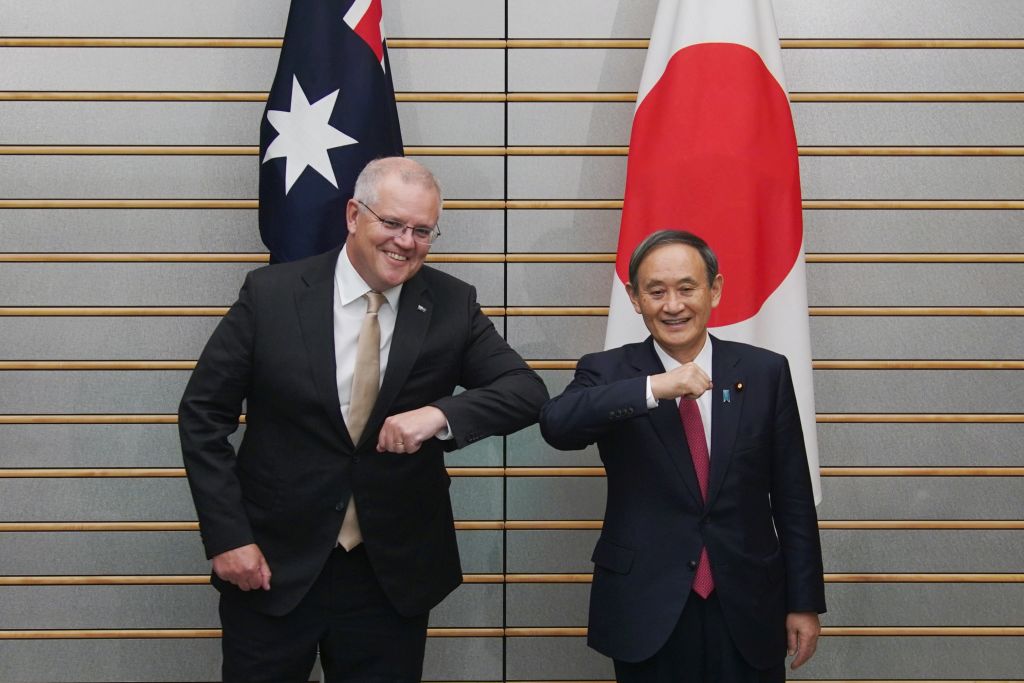

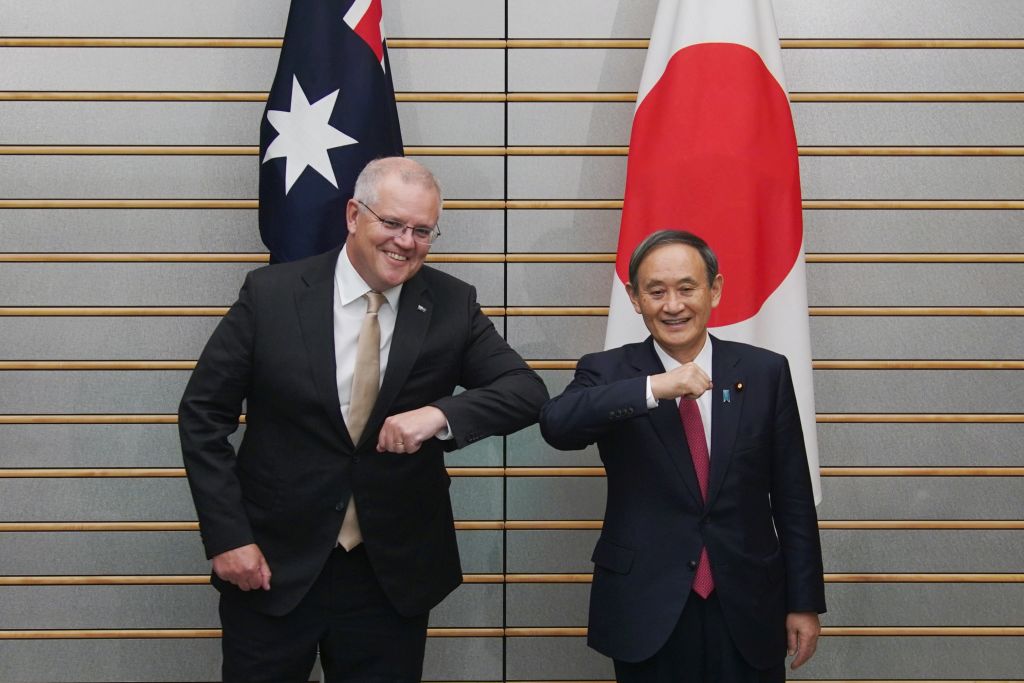

Japan is ANZUS’s most important Indo-Pacific security partner. Tokyo shares the regional outlook of Australia and the US, possesses advanced defence capabilities and is eager to work towards common objectives. Japan’s transformation from a postwar security dependant to a trusted security partner is a remarkable evolution and a much-needed addition to the emerging Indo-Pacific architecture. As Australia and the US mark 70 years of ANZUS, one of the most important ways Australia can support the keystone of its defence and security is through shoring up bilateral cooperation with Japan and exploring new frontiers in the trilateral Australia–US–Japan arrangements.

For decades, Australia and Japan viewed their relationship primarily in economic terms, but, since the early 2000s, the defence relationship has grown in leaps and bounds. The two nations have established a joint declaration on security cooperation, acquisition and cross-servicing, an information security agreement, a foreign and defence ‘2+2’ ministerial meeting and the joint air force Exercise Bushido Guardian. The relationship has grown beyond basic defence exercises as Tokyo and Canberra are now seeking interoperability between their armed forces and the capacity to respond jointly to shared challenges. The next step in the bilateral defence relationship will be to finalise a status of forces agreement, known as the Reciprocal Access Agreement (RAA).

The RAA will be Japan’s first status of forces arrangement with any partner beyond the US. This historic step will demonstrate the intimacy of the Australia–Japan relationship and provide the Japan Self-Defense Forces (JSDF) with greater flexibility to access and work with a key US ally. It will be of particular benefit to Japan, giving it the opportunity to use Australia’s large, remote training facilities, and benefit each country through improving ADF–JSDF coordination. Moreover, by improving interoperability between Australian and Japanese forces, the RAA will also benefit the US by enhancing coordination within its existing alliance framework.

While the RAA is undergirded by strong bilateral relations, the fast pace of growth in Australia–Japan defence cooperation is arguably the result of external security developments. In particular, China’s increasingly aggressive posture and waning confidence in future US security commitments to the region have weighed heavily on Japanese and Australian policymakers.

Chinese hostility is evident in the militarisation of the South China Sea, harassment of foreign vessels and aircraft in disputed territories and targeted cyber intrusions and attacks. Frequent Chinese military incursions around the disputed Senkaku Islands as well as Beijing’s support for the North Korean regime have increased Japan’s anxiety. In Australia’s case, Chinese-backed cyberattacks and punitive trade measures have rattled Canberra. More than any other dynamic in the region, China’s bullying behaviour has convinced Japan and Australia they need to invest more in their security partnership.

In terms of US credibility, concerns in Australia and Japan regarding the extent of US security commitments to the Indo-Pacific were generated long before the uncertainty wrought by the Trump administration. From the early 2000s, America’s allies in Asia were encouraged to bolster their national defence capabilities and enhance coordination with each other. That, coupled with decades of US attention and resources directed overwhelmingly towards wars in the Middle East, has brought America’s allies in the region closer together.

Once Donald Trump took office, his harsh rhetoric and occasional embrace of authoritarian regimes hastened the trend. The Biden administration is much more receptive to allies’ needs and shares Australia’s and Japan’s interest in closer security ties, using both bilateral and trilateral modalities. The strength of trilateral defence cooperation between Australia, the US and Japan is unique and provides each with a competitive security advantage.

Australia first proposed a trilateral dialogue with Japan and the US in 2001, and the trilateral framework was formalised in the following year. Trilateral meetings now range from the senior officials level to foreign and defence ministers, up to prime ministerial and presidential summits. In addition, practical defence cooperation includes both tabletop and real-world military exercises. To capitalise on the success of the trilateral, the three countries should continue to jointly pursue increasingly high-end defence activities. That includes intelligence sharing; intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) activities; and cooperation in the cyber, space, science and technology domains in practical military exercises.

Based on the history, depth and breadth of their relationships, the trilateral structure can initiate collaborative security initiatives matched by no other regional defence grouping. In future, the trilateral could be bolstered by more Australia–Japan bilateral defence exercises in the vicinity of Japan and Australian participation in trilateral activities to practise defending Japan against missile debris or a missile attack. For instance, in the event of future North Korean missile launches and belligerent behaviour, the Royal Australian Navy’s Aegis-equipped vessels could provide Japan with air defence and intercept those threats. The three countries could also conduct combined ISR activities—in addition to UN-mandated missions—to monitor North Korean ship-to-ship transfers that circumvent trade sanctions.

Should the regional outlook deteriorate, another way to elevate cooperation could be for the three countries to privately identify concrete scenarios to embed in their military exercises. For example, designing operational planning around specific contingencies, such as a serious threat to Japan’s territory or conflict in the Taiwan Strait or South China Sea, would provide a clearer strategic objective for our combined military exercises. While Australia would seek to avoid a conflict as much as possible, it would most likely be compelled to influence the outcome of a major inter-state conflict in our region, whether in the form of logistics support or the provision of military forces in some capacity.

More than any other countries in the region, Australia and Japan recognise the stability flowing from the US alliance system. Both are steadfast in their support for continued US engagement, the preservation of democratic processes and systems, and the underwriting of future growth and prosperity through investing in new security frameworks.

Moreover, there’s growing acceptance that regional security challenges—be they pandemics, climate change, assuring supply chains or defending a rules-based system—can be addressed effectively only through collective action. As three countries facing multiple challenges, the Australia–US–Japan trilateral has an enduring value for the future of the ANZUS alliance, alongside bilateral Japan–Australia security ties.

Print This Post

Print This Post