On Twitter, Instagram and Facebook, a network of accounts is targeting the West Papua independence movement with memes and messages designed to shape international and domestic narratives about the separatist movement.

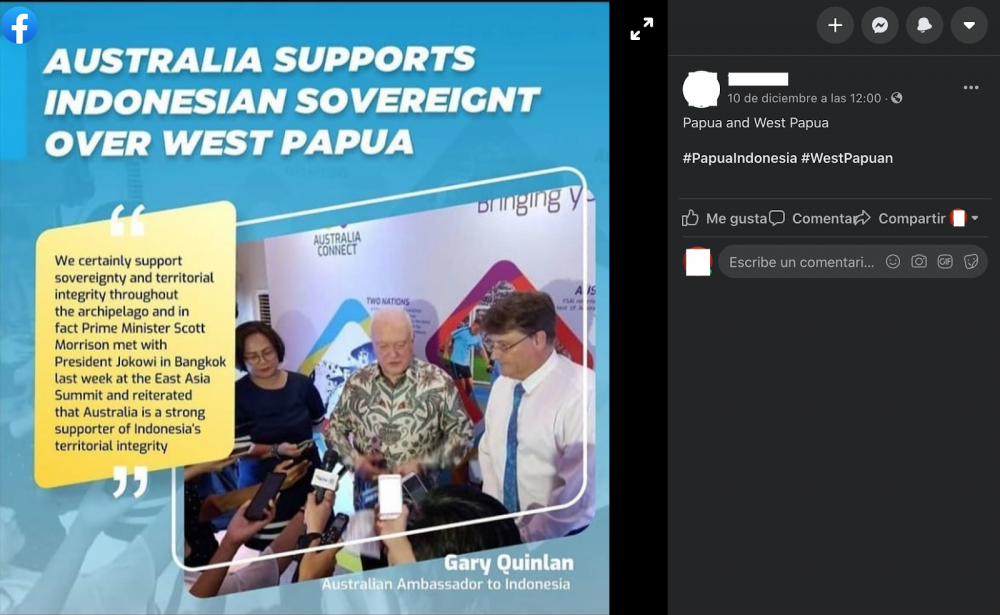

The region has been beset by a series of well-documented online information operations, but some of the content posted in late 2020 claims to represent the views on West Papua of Australian officials, as well as of the United Nations and the UK government, and have reportedly been called out by the Australian government.

A former Dutch colony, West Papua became part of Indonesia in 1969 after a heavily disputed referendum. The Australian government does not dispute Indonesia’s sovereignty over the region, despite the ongoing claims of indigenous Papuans. Some Pacific island states have expressed support for Papuan independence and raised alleged human rights abuses at the United Nations General Assembly.

In 2019, the BBC and ASPI’s International Cyber Policy Centre described coordinated social media campaigns that appeared to target international audiences with anti-separatist messages using a series of websites, which were amplified on Twitter. One was conducted by Indonesian media company InsightID, as confirmed by Facebook. In late 2020, Bellingcat reported on another network operating across Twitter, Facebook, YouTube and Instagram that bears many similarities with the one discussed here.

ASPI examined a sample of accounts sharing unauthorised infographics claiming to represent the views of Australia and other countries on West Papua across social media. The network also shared messages that suggest West Papuans don’t support independence and that Indonesia has brought prosperity to the region, among other narratives.

Some messages were attributed to Australian diplomat Dave Peebles and Gary Quinlan, Australia’s ambassador to Indonesia. There were also posts that claimed the UK supports Indonesian sovereignty over Papua, with reference to UK diplomat Moazzam Malik and UK Minister for Asia Nigel Adams. Messages stating that the UN rejects West Papua’s claim for independence were attributed to UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres and Rafael Ramirez, a former UN envoy for Venezuela. Other posts attacked Vanuatu for discussing Papua at the UN in September.

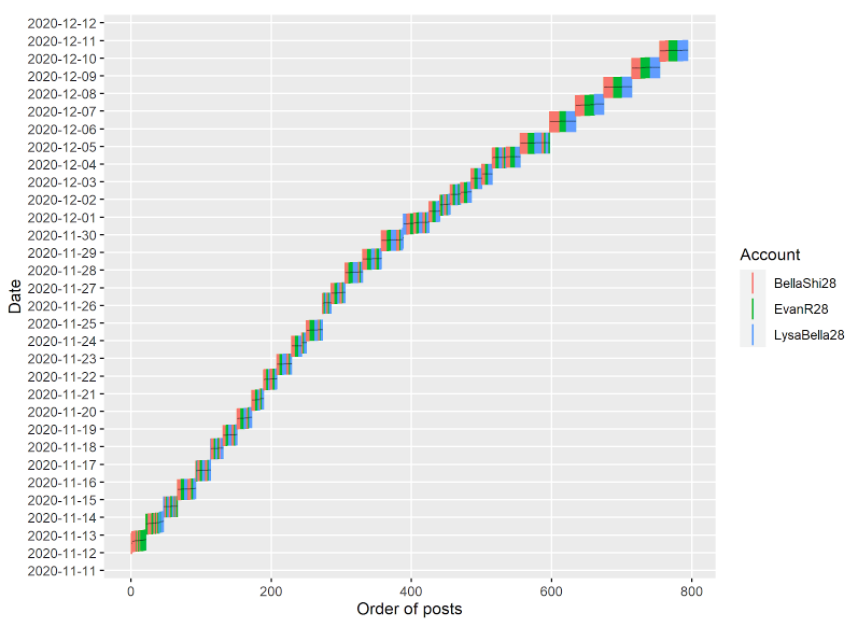

Our analysis of accounts posting the images on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram revealed signs of coordinated or automated posting. This is consistent with previous activity relating to the region: ASPI examined a dataset of accounts targeting the West Papuan movement that were taken down by Twitter in April and found evidence of highly automated accounts posting in 30-minute intervals.

Our analysis of the most recent network found that a sample group of four Instagram accounts posted similar images around the same time each day in quick succession with the same hashtags and in a consistent order. Such behaviour may suggest a single operator of all four accounts.

Likewise, on Twitter, one group of three accounts also posted in a coordinated manner. BellaShi28 (red) would post first every day, followed by EvanR28 (green) and then LysaBella28 (blue). From 6 December onwards, the posting behaviour of these accounts became more consistent, suggesting that the operator of the accounts or the capabilities of the operation improved.

Some Facebook profiles also display similarly coordinated posting schedules. On 9 December, two accounts examined by ASPI posted 50 and 49 infographics about West Papua between 20:23–20:34 and 20:52–21:05, respectively, in largely the same order and in quick succession. All had the same set of hashtags: #FreeWestPapua, #vanuatu, #otsuspapua, #lanjutkanotsus—the latter two referring to West Papua’s special status within Indonesia.

The Twitter and Instagram accounts appear to have attracted little engagement so far, but their occasional use of English and Dutch instead of bahasa Indonesia seems calculated to influence international conversations about the issue. On Facebook, some accounts whose profiles were set up to appear as if they were locals in West Papua attracted slightly more interaction.

Many of the accounts used profile images that don’t appear genuine, consistent with past social media influence campaigns targeting West Papua. Profile photos were taken from image services such as Getty, news articles and other Instagram profiles, for example. Other accounts used images that were possibly created by a GAN (generative adversarial network), a phenomenon Bellingcat also observed, which uses machine learning to create new images from a training set of past images.

GAN images can sometimes be identified due to small imperfections, such as irregular backgrounds. In the image below, for example, the blurred and warped tree or column (circled in yellow) in the background suggests this Twitter profile image is a GAN.

A number of the Facebook accounts sharing the infographics link to and claim on their profiles to be affiliated with West Papuan independence Facebook pages, despite sharing memes that largely argue against the movement. One such independence page used terms associated with the Free Papua Movement and the West Papua National Liberation Army. The intended audience of its posts seems broader than West Papua: the language used is highly standardised without Papuan-specific slang, which means it could be read across Indonesia.

Overall, the narrative of the infographics we examined seems designed to strengthen the perception that Indonesia has international support for its sovereignty over West Papua and to quash hope of outside assistance with independence for the region. While the accounts we examined attracted only a relatively small amount of interaction, information campaigns on West Papuan issues have been persistent, and this is likely to be only a small part of operations designed to spread pro-Indonesia narratives.