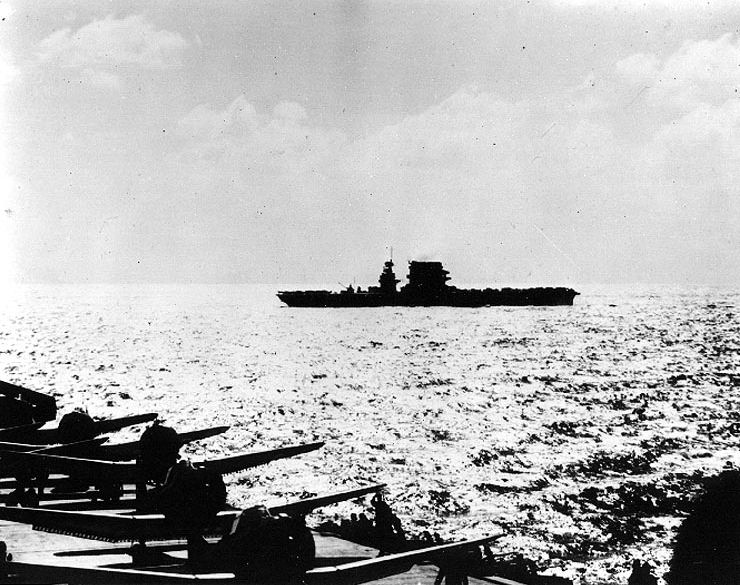

The Coral Sea, 1942: a nation-saving battle

Posted By Kim Beazley on May 3, 2017 @ 14:30

The Battle of the Coral Sea isn’t as iconic in our national consciousness as Gallipoli, Kokoda, or even El Alamein, Villers-Bretonneux, Amiens or Beersheba. Those battles and others in the two world wars played into our evolving sense of what we were, and are, as a people, and our national character.

Coral Sea stands to the side. It was a critical event stabilising what seemed to be a freefalling disaster in our strategic situation as the Japanese thrust south punctured every assumption we had of the decisive value of imperial defence. Our anxiety was magnified by the Japanese rolling up every island we’d defined as critical to our national fortress, and they were now dragging down the drawbridge in Papua New Guinea.

Coral Sea was nation-saving not nation-creating. It was a materialisation of the validity of the judgement on the need to shift our assumptions about allies Curtin enunciated in an article in the Melbourne Herald on the eve of our year of living dangerously: ‘Australia looks to America, free of any pangs as to our traditional links and kinship with the UK.’

That was hard calculation. The emotional dénouement is in Curtin’s spine-tingling speech to parliament on 8 May 1942, when the battle was in progress: ‘As I speak, those who are participating in the engagement are conforming to the sternest discipline and are subjecting themselves with all that they have—it may be for many of them the last full measure of their devotion—to accomplish the increased safety and security of this territory.’

Outside specialist historians and the US Navy, the battle doesn’t resonate for Americans like Pearl Harbor, Midway and the island campaigns to Japan, but they’ve come to understand that it looms large in our strategic consciousness.

Some strategic thinkers see the Coral Sea as imprisoning our imagination and they believe we need a strategic rethink as profound as Curtin’s. The region and globe are rebalancing. We need to rebalance regionally to account for new rising powers. Coral Sea is a narrative of a time with a very different regional power distribution that’s not relevant today. But it retains currency in how we assess our ally. Our view of the relationship has been formed in an era of massive US dominance. As power becomes more diffuse it feeds a perception of the diminishing value of the relationship, particularly whether or not it’s worth spending political capital sustaining it.

Assessments of Coral Sea need freshening up in this post–Cold War, Asia-rising era. Two lessons are very relevant today. The first is the type of ally the US might be in an era in which it’s not necessarily preeminent. The second is what the US default position in our region is when its saliency in our broader region’s under pressure.

It’s extraordinary that the battle was fought at all. It was a very high-risk undertaking by our very new ally when the prospect of the Japanese taking Hawaii was high. Were the Americans to lose the base, the fight-back would have been anchored in San Diego. At the outbreak of war the geopolitics of the Asia–Pacific were dominated by the European empires and rising Japan. US power would need some years to mobilise.

The US was aware it would have to fight a major battle at Midway within a month. That stepping stone had to be denied to Japan to prevent another strike at Hawaii. The Japanese were superior in carriers, battleships and shore-based air strength. They deployed eight fleet carriers and six light carriers, to the US Navy’s four fleet carriers. Cautious advice suggested the US should concentrate around Hawaii until construction caught up. American land-based air power on Hawaii had been much improved but still, to commit half your carrier strength knowing you faced a major battle a month hence, was risk-taking of a high order. The US put its territory at risk to support an ally.

We like to talk of 100 years of allied collaboration stretching back to World War I. But the two decades before 1942 had seen Australia devoted to European empire in Asia, and the US opposed to it. We were a newly minted friend on which to spend priceless capital. The lesson here is that the US will go a long way for a friend whether or not it’s the preeminent power.

The second lesson is one of geopolitical calculation. Coral Sea revealed the US default point in the Pacific, which involved much debate and disagreement in the Roosevelt administration. The strategic determination, agreed between Roosevelt and Churchill, was to ‘beat Hitler first’. The question was whether the US should fight back from the central Pacific or the south, given its inferior forces. Admiral Ernest King, an equal with General George Marshall as an adviser to Roosevelt, conceded that the Germany-first strategy allowed ‘very few lines’ of military endeavour in the Pacific.

King’s line anchored on defence of ‘Australasia’, securing the chain between Australia and Hawaii. ‘Such a line’, he said ‘would be offensive not passive’. He envisaged it for the Solomons but then soon Papua. Thus the American carriers turned up in the Coral Sea. Their reward was taking two fleet carriers the Japanese had assigned to that task out of the Midway battle. The US faced four, rather than six, carriers to its three. The advantage intelligence gave them, and luck on the day, meant that they won.

King’s default position remains the American default position. Currently they are forward in the northern Pacific, which conceals their default position. Were they to leave, or be pushed back from their northern commitments, the geostrategic factors that drove King’s calculation about us in the south would remain.

Article printed from The Strategist: https://www.aspistrategist.org.au

URL to article: https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/rethinking-the-battle-of-the-coral-sea/

Click here to print.