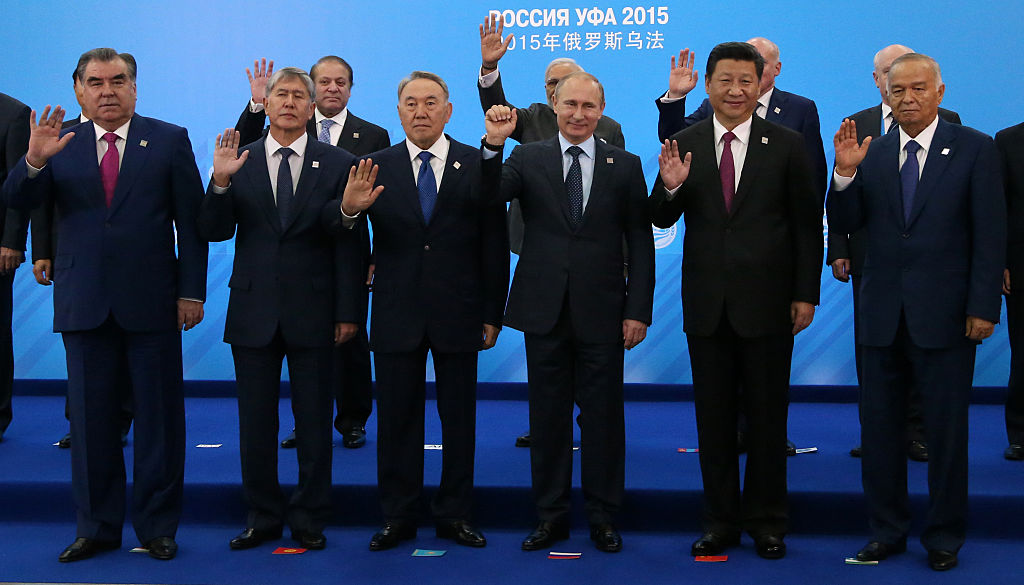

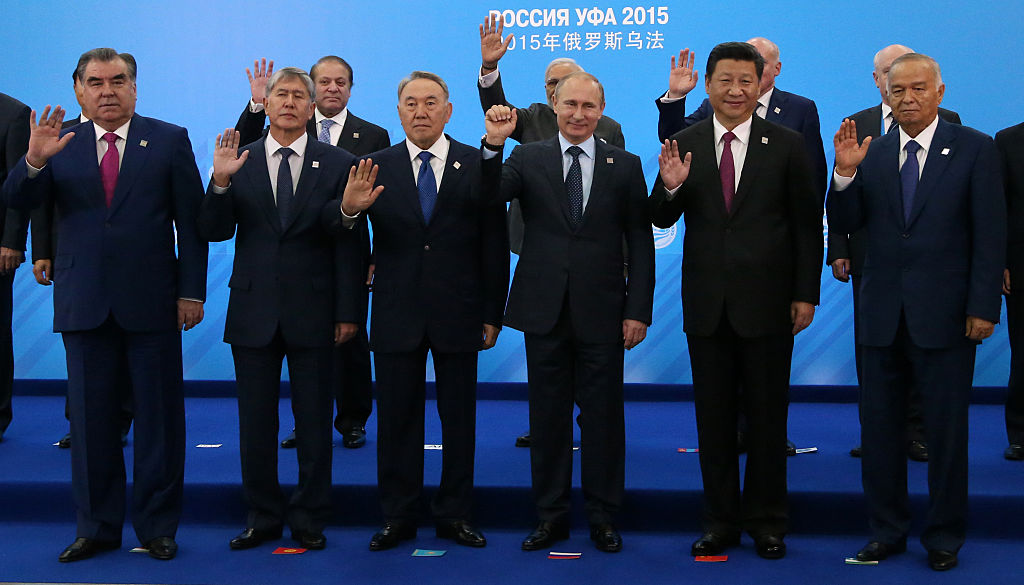

The Western media will focus its coverage of the

Shanghai Cooperation Organisation summit beginning today in Uzbekistan on the dynamic between three of the most powerful leaders in the world—Chinese President Xi Jinping, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Of particular interest will be the expected bilateral between Xi and Putin, their first in-person meeting since they forged their ‘no limits’ partnership just before the invasion of Ukraine began in February. The timing of this year’s SCO meeting may also draw some of the limelight away from the one-year anniversary of the AUKUS agreement, also taking place this week.

However, beyond all the awkward photoshoots and the turgid joint statements in Samarkand, there’s likely to be relatively little focus on the SCO itself. That seems a mistake given that, by its own estimation, the forum encompasses

nearly 30% of global GDP (calculated by purchasing power parity) and almost half the world’s

population.

In this explainer, a team of ASPI experts provide some perspective on the SCO, its members and their aims.

What are the SCO’s origins and how has it grown into its current shape?

The SCO emerged from the so-called

Shanghai Five in 1996, a security dialogue between China, Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, which was forged days after a bilateral summit announced the first post–Cold War iteration of the Sino-Russian strategic partnership. As its origins reveal, the progress of the SCO has rested on warming Sino-Russian relations.

The SCO was founded in 2001 and had its inaugural meeting in Shanghai. Its original membership expanded from China, Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan (that is, all the Central Asian republics except Turkmenistan) to include India and Pakistan from 2017.

Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi, who is also attending this week’s summit, is expected to sign a memorandum that will move Iran further along the path to full membership in 2023. A broad and growing number of countries across Eurasia and the Middle East participate as observers and dialogue partners, stretching from Cambodia to Belarus.

The SCO has enjoyed observer status at the UN General Assembly since 2005. The timing of the summit facilitates leaders comparing notes before many of them depart for the UN General Assembly high-level meetings starting next week in New York.

What binds the SCO’s members together?

Internally, the SCO claims to find some sense of consensus around the concept of the ‘

Shanghai spirit’, which emphasises mutual respect, ostensibly in the same vein as the ‘five principles of peaceful coexistence’ developed by China in the 1950s. Like its Cold War antecedent, the Shanghai spirit is a reiteration of norms of state sovereignty and non-interference—an attempt to paper over a range of tensions within and between members.

Geopolitically, the SCO draws on the geographic concept of Eurasia—a continental heartland that retains surprising currency and ideological gravity in a wide range of countries, including Turkey, a NATO member. Some of its members have styled the SCO as a counterweight and alternative to the US-led liberal world order, although that vision is not universal and is far more attractive to countries such as Russia and China than it is to others such as India.

Experts have

debated the extent to which 2005 marked a turning point. That’s when the SCO rejected US observer status and, led by Uzbekistan, called for the withdrawal of a ‘foreign army’ (read: US Army) from the SCO sphere.

Western analysts have at times discounted the SCO as toothless and internally divided. That may be the case to some extent, but the SCO’s combination of an imagined Eurasian community, Westphalian norms and exclusion of the West seems sufficient basis for the format to survive and grow.

What does the SCO do besides meetings?

The original six members

pledged to work together to ‘combat transnational security threats in the form of ethnic separatism, religious fundamentalism, international terrorism, arms-smuggling, drug trafficking and other cross-border crime’. This is the basis of what are sometimes called the ‘three evils’ of terrorism, separatism and extremism, which remain priorities for the SCO even if members have different interpretations of the boundaries of these terms.

Over the past two decades, supported by an increasingly complex institutional framework, the SCO has added trade and economic security issues to its remit. It has also conducted regular military exercises, called ‘peace missions’. They are ostensibly aimed at combatting the three evils but resemble military drills potentially aimed at Russian or Chinese adversaries. These exercises have included heavy military assets such as strategic bombers—hardly suitable platforms to put down a colour revolution.

What has China’s role been in establishing and shaping the SCO, and to what ends?

An often-overlooked driver for China’s participation in the SCO has been shaping regional responses to align with Beijing’s domestic objectives in Xinjiang. The institutional focus on the three evils reflects Beijing’s targeting of any groups and individuals whose views and activities are deemed a threat to the Chinese Communist Party, including beyond China’s borders.

Throughout the

mid- to late 1990s and early 2000s, China began to

attribute a number of ‘terrorist incidents’ in Central Asia and Xinjiang to Uyghur separatists. These included, for instance, a June 1998 explosion in Osh, Kyrgyzstan, and a May 1998 arson incident in Urumqi.

In exchange for security and economic support, Beijing has expected SCO members in Central Asia to

comply ‘unconditionally’ with requests to transfer wanted individuals across borders, engage in

paramilitary cooperation including joint patrols with the People’s Armed Police, and turn

a blind eye to oppression in Xinjiang.

Despite the economic dimensions at play, we should be cautious about casually drawing links between the SCO and China’s Belt and Road Initiative. A proper understanding of the nexus should always be embedded in a wider analysis of the CCP’s aims and behaviour.

Why does India, a Quad member, choose to participate in the SCO?

It’s uncomfortable for Quad partners to see India’s seemingly contradictory membership in the SCO. Modi standing next to Putin and Xi in Samarkand will only raise speculation in the West over New Delhi’s intentions.

But New Delhi’s membership in the SCO must be understood through India’s perception of Chinese and Russian influence in its region.

India became a member of the SCO in 2017 after 12 years as an observer, driven by concerns over China’s growing relationship with Central Asian states and a need to monitor Pakistan–China cooperation in counterterrorism.

New Delhi doesn’t see its membership of both the SCO and the Quad as contradictory. It is equally alarmed by the Chinese–Russian

‘no limits’ friendship, and a thaw in the India–China relationship is unlikely given their active border dispute.

From India’s perspective, the SCO provides a platform to rejuvenate its floundering relationship with Central Asia and, more importantly, an avenue to cripple China–Pakistan cooperation efforts on important security issues, such as counterterrorism in Afghanistan.

None of this should prevent us from challenging New Delhi’s relationships with Moscow and Tehran, or its unwillingness to openly condemn Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

However, India’s participation in both the Quad and the SCO should be seen as what it is—an effort to improve its regional standing and counter China’s rising influence—rather than an attempt to play both sides.

On balance, India is more invested in the Quad, which, unlike the SCO, provides opportunities for prosperity and the provision of public goods. Indian foreign minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar recently

called the Quad ‘the most prominent plurilateral platform that addresses contemporary challenges and opportunities in the Indo-Pacific’.

What is the SCO’s position on Afghanistan, and could it help there?

The burden of shared geography means an unstable Afghanistan has always been a direct security concern for SCO members.

An SCO–Afghanistan contact group was established in 2005. Afghanistan received SCO observer status in 2012. Cooperative efforts under the auspices of the SCO’s

Regional Anti-Terrorist Structure have been aimed at counternarcotics and counterterrorism initiatives, including an Afghanistan–SCO ‘plan of action on combating terrorism, drug smuggling and organised crime’.

Some SCO members have pursued minilateral initiatives like the Quadrilateral Cooperation and Coordination Mechanism agreed between Afghanistan, China, Pakistan and Tajikistan in 2016, focused on border security. However, despite much rhetoric in the SCO, most concrete initiatives have remained at the bilateral level.

Looking ahead, just as many bilateral initiatives during the International Security Assistance Force era focused on countering NATO, the SCO could act as a dialogue platform for drumming up anti-Western sentiment.

The overarching priority for SCO members has always been furthering their domestic security agendas rather than developing an effective institutional mechanism for stabilising Afghanistan. This trend has continued since the Taliban returned to power in August 2021.

We might hope, but should not expect, that the SCO will convert some of its ambitious rhetoric into actions that actually help the Afghan people.

Print This Post

Print This Post