As Foreign Minister Julie Bishop and Defence Minister Marise Payne get ready for next week’s annual Australia–US Ministerial Consultations with their US counterparts, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and Defence Secretary Jim Mattis, their biggest concern must be the future of the alliance under the increasingly bizarre presidency of Donald Trump.

The doubts won’t be on display. As one of the few adults in Trump’s cabinet, Mattis is a strong alliance supporter. We undoubtedly will see an AUSMIN declaration proclaiming a confident future for the alliance, one that overlooks Trump’s destructive path via Kim Jong-un, the G7, NATO, Brussels and London to his unrecorded meeting with Vladimir Putin.

There is every reason the Australia–US alliance should flourish. Both countries get huge value from it. But reason is not the currency of choice with Trump.

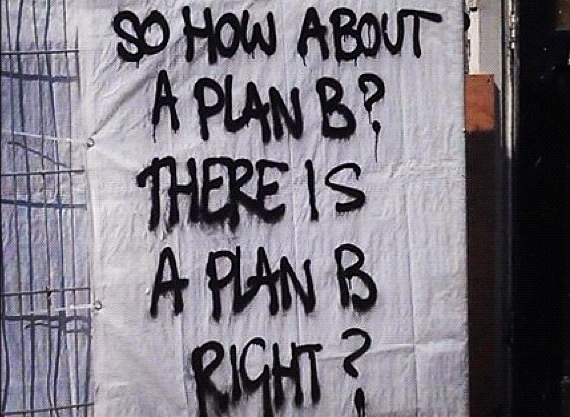

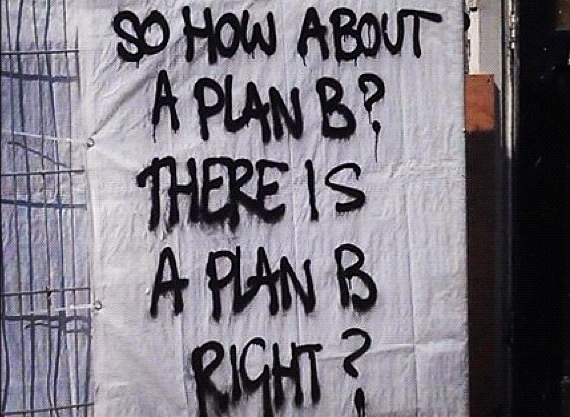

Malcolm Turnbull and his colleagues must do everything they can to sustain the alliance, to shelter it from Trump’s distaste for these entanglements, but it’s timely to think about Plan B.

What’s the plan for Australia’s defence if it turns out that Trump’s ‘America First’ approach is here to stay and alliances fall into mistrustful neglect?

Here’s a general rule about the reality of defence planning: the bigger the problem the less likely it is that we will have a plan for it. That may surprise you because people imagine national security types always plan to deal with worst-case scenarios.

No so. At the beginning of my Defence career in the early 1990s I’d imagined there was a plan to respond to East Timor’s possibly messy departure from Indonesia. News reporting clearly showed trouble brewing. But there wasn’t a glimmer of a Defence plan for that contingency until late in 1998.

Why this chronic planning avoidance? Government couldn’t tolerate developing a Plan B because that would call into question the reliability of Plan A—in this case that we supported Indonesia’s bloody incorporation of East Timor. Defence was in its comfort zone implementing Plan A by building defence ties with Jakarta.

Fast-forward a quarter of a century to Trump’s efforts to trash US allies, and treat the EU as a foe and Russia as a friend. Does any of this suggest it’s time to think of a Plan B for Australian defence policy?

The 2016 defence white paper shows that the current Plan B is even more of the alliance’s Plan A. The design of our navy and air force hinges on the alliance getting even closer. If alliance cooperation ended, we might as well close some of our intelligence agencies and get used to dealing with the region substantially blindsided.

My assessment is that we don’t face a future cut off from alliance cooperation. The US will still want to sell us defence equipment and the Americans get major benefits from intelligence cooperation.

The bigger risk is that an America First strategy will see US military personnel leave South Korea and Japan. Trump may ask why US marines are working out of Darwin, seeing the bill but not the benefit of a military presence reassuring Southeast Asia that America is standing by the region.

That’s where an Australian Plan B for our defence posture should come in. The alliance may survive for technology transfer and intelligence, but that may be the practical limit of the US’s interest in Asian security under Trump.

Australia’s Plan B must work on the assumption that we will have to do more for our own security, play a stronger leadership role in the region, reconsider the size and strength of the defence force, and position ourselves for even darker threats to our security, without confidence in the US security umbrella.

Here are 10 steps to give Australia a stronger defence capability and a leading position in regional security. If this looks a bit scary, rest assured that few are thinking this way in Canberra. Just like the East Timor situation in the ’90s, we will go with Plan A until a strategic shock jolts us onto a different path.

First, we should start to lift defence spending to reach 2.5 or 3% of gross national product in a decade. On current plans and spending around 2% of GNP on defence, we will spend a total of $497 billion across the next 10 years. My ASPI colleague and defence economist Marcus Hellyer crunched the numbers: the bottom line is that growing at a steady rate to reach 2.5% in 2028 adds an extra $57 billion to planned defence spending. A 3% target adds an extra $122 billion.

The additional money will buy extra military gear, but the figures tell you that the top priority must be to get our spending plans right; we must speed up delivery dates and make sure the defence force is at high levels of readiness. We can’t afford a repeat of the ‘fitted for but not with’ era of the ’90s when large parts of the military were simply not equipped to fight.

Second, we need to lift our own leadership game in regional security. Australia should conclude a defence treaty with Japan, the most consequential democratic regional power. We also should look to sign an alliance with NATO’s two most effective defence powers, France and Britain. These groupings can’t replace an isolationist US, but they are the core of the democratic, rule-of-law-supporting countries. As the saying goes, we will hang separately if we don’t hang together.

Third, Australia must invest in building strategic partnerships with Indonesia and India. Currently Jakarta presents no conceivable threat to Australia. Now is the time to use every means we can to help build an Indonesian military force that is irrevocably aligned with Australia. It will be harder work with India, but that points to the need for an investment in relationship-building.

Fourth, we need to accept that Australia can lead or lose the Pacific island states. We are losing to an influx of Chinese money that is aimed at corrupting elites. In return for residency rights, we should look to formalise our role as the defence and security guarantor for Nauru, Kiribati, Tuvalu and other microstates. That will mean stationing navy patrol vessels in some locations and lifting our active defence presence.

If we don’t acknowledge the reality that the Pacific is uniquely our security challenge, the region will turn into a de facto Chinese lake within a decade.

Step five: it’s time to invest in building a nuclear industry able to support a fleet of nuclear-powered submarines. You can forget the assumption made in so many newspapers’ letters pages that the US will sell us Los Angeles–class nuclear-powered attack submarines. The only way Australia can develop a nuclear navy is to build the skill base ourselves.

Nuclear propulsion will give our submarines the range and endurance to act as the core of an Australian deterrent capability.

Linked to a stronger submarine force is step six: we need to equip our subs with long-range cruise missiles as planned in the 2009 defence white paper. Operating outside of an alliance construct, Defence needs to acquire the ability to hit targets at very long range, firing cruise missiles from hard-to-detect ships and aircraft.

A substantial part of the defence budget increase must be used to give our forces more hitting power. This would include (step seven) working with the US as a commercial proposition on its plan to develop a long-range bomber aircraft.

Step eight: we need to copy what the Germans have just decided to do—develop a defence advanced research projects agency, similar to the American DARPA. An Australian DARPA would work on the next generation of technologies such as artificial intelligence, hypersonics and autonomous systems. Currently only about 0.5% of the Defence budget is spent on innovation programs. That’s not enough to keep pace with changing technology. The Australian DARPA should operate as a stand-alone agency working outside the mores of Defence.

Step nine: we need to do more in cyber, not simply protecting our systems but also developing a formidable cyber offensive capability that will be a strong deterrent to attackers. The Australian Signals Directorate should be doubled in size well within the decade.

Finally, I would aim to increase the Australian Defence Force to about 90,000 personnel, up from the current 58,000 regulars. This takes us to the 3% of GNP spending level. A force that size still would be tiny by regional standards but would vastly strengthen our ability to operate the hi-tech equipment.

Taking these steps would create a much more powerful case for the US to invest in the alliance. I have no real expectation that we will go down this path anytime soon. These are hard policy choices when governments of all political stripes are more focused on minimising risk.

But the risk is that our worsening strategic outlook will force Australia into adopting a stronger deterrence-based defence posture. Hopefully that still will be in an alliance context with the US.

Print This Post

Print This Post