The government’s recent announcement of a

further delay to the $7.9 billion Air Warfare Destroyer (AWD) project has been met with a degree of cynicism. Although the government says that the delay is needed to

preserve workforce skills in the maritime sector, some have suggested that the latest delay had

more to do with returning the federal budget to surplus. Others have argued out that the delays are

unlikely to close the looming gap in local naval construction work in any case. So what’s going on?

Let’s have a look at what we know. To start with, the latest round of delays is relatively small; the first vessel has been delayed an extra three months, the second by six months, and the third by nine months. The progressive slippage in the schedule is shown in the table below. As can be seen, the most of the slippage in the program occurred in the 2011 after problems were encountered with the construction of modules.

Table: Progressive delivery schedule for the AWD project

|

Original delivery date

|

2011 reschedule

|

2012 reschedule

|

HMAS Hobart

|

December 2014

|

December 2015

|

March 2016

|

HMAS Brisbane

|

March 2016

|

March 2017

|

September 2017

|

HMAS Sydney

|

June 2017

|

June 2018

|

March 2019

|

The next thing we know is that the delays will result in around $100 million being shifted out of the forward estimates period—the next four years—into the epoch beyond. Now that is a lot of money in most people’s books, but in terms of the federal budget it’s a rounding error. Consequently, we can discount the possibility that the government is harvesting a further round of savings in preparation for the mid-year budget update (though that may yet occur!).

Nonetheless, it may be that Defence is eager to alleviate some of the internal budget pressures created by the $5.5 billion cut over four years imposed in the May budget. The amount of money set aside for approved capital investment projects was one of the prime sources of ‘savings’ returned to government, especially over the near term, with roughly half a billion dollars cut from this year alone. With that sort of pressure bearing down on DMO, $100 million over four years would be a welcome relief—though probably not reason enough on its own to justify a rescheduling of the AWD project.

Another factor, which may have affected the decision at the margins, is the new eighteen month interval between the arrivals of successive vessels. Navy has a lot on its plate with the looming introduction of both the Landing Helicopter Docks and the AWD, and the additional time will lessen the challenge of introducing the two new classes of vessel into service.

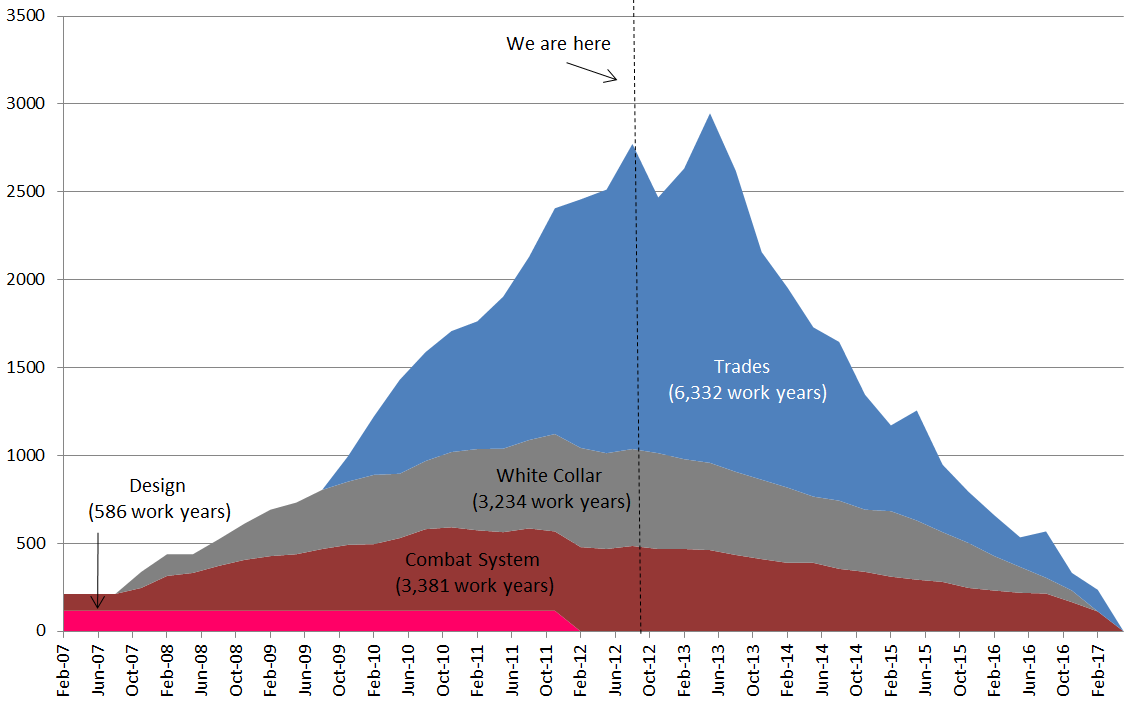

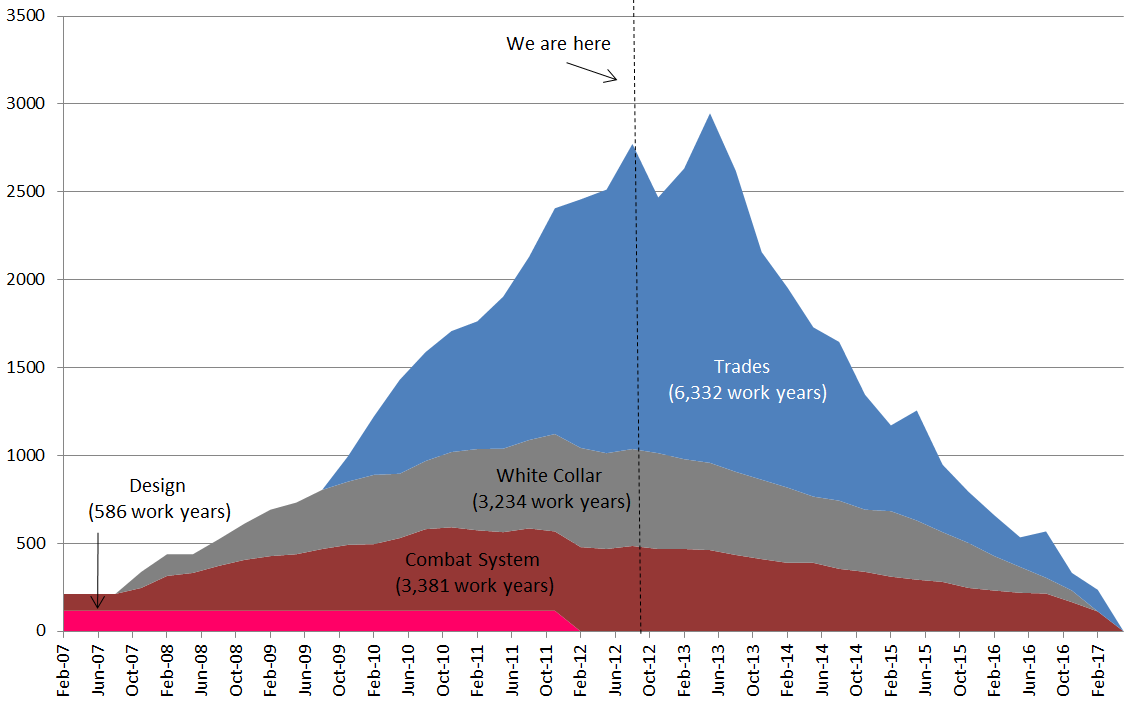

Turning now to look at the question of work continuity and the retention of skills in the maritime sector, consider the workforce profile for the AWD project prior to the latest rescheduling. Note that most of the workforce was planned to have dissipated well before the delivery of the final ship. This is certainly still going to be the case except, that the schedule has been shifted nine months to the right. Thus, even with the reschedule, most of the workforce will have moved on from the maritime sector by 2016. Given that the Future Submarine project is not due for second pass consideration until 2016–17 at the earliest, how can the reschedule have possibly been beneficial in terms of maintaining skills in the sector? The answer is that it cannot. Under existing plans, the so-called valley of death remains in place (it’s the right-hand slope of the workforce mountain below, click to enlarge).

Graph: AWD workforce demands – alliance plus local contractors. (Source: presentation by Defence official, January 2012)

Setting aside the possibility that the government is simply spinning a line on the workforce issue, this means that there is something new being considered by the government for the maritime sector. There are several possibilities:

- The Future Submarine project could be brought forward by making an early choice to go with the assembly of an entirely MOTS submarine in South Australia. This seems unlikely; although a MOTS design is being considered, the government appears to be taking an orderly and systematic approach to the choice of submarine design with little prospect of an early decision.

- An order could be placed for a fourth AWD. This is not beyond the realm of possibility, but we’ll know soon enough given the lead-time to purchase the radar from the United States under the Foreign Military Sales Program.

- The Offshore Patrol Combatant project could be brought forward to avoid a gap. But this seems unlikely given that it would use only a subset of the advanced skills needed in the maritime sector, and would probably be best acquired under a competitive contract to give other Australian firms a chance to bid.

- Finally, the Future Frigate project could be brought forward. Although this option would make use of most of the advanced skills presently being employed on the AWD, it would be difficult to mobilise a new project of that complexity in the time available. However, one option would be to initiate a ‘crash program’ based around the existing AWD hull but with less advanced sensors and weapons.

It will be interesting to see what the government has in mind to close the gap in naval construction demand. The delays to the AWD project are not a solution; at best, they open up a series of possibilities, each of which would demand bold action. And then there’s the question of money. All signs are that defence spending will remain tight over the near to medium term. Can we afford a make-work program to keep naval construction ticking over in South Australia? And even if we can, does it make sense to rush the submarine program or retire the ANZAC class of Frigates early to do so?

Finally, there’s a curious point to be considered about what we’ve been told. According to the Minister the ‘

new schedule will not increase the cost of the project’. At first blush, this is difficult to make sense of, at least from an industrial production perspective. By extending the project by nine months, the overheads due to the fixed administrative and engineering workforces will be extended, as will facilities operations costs. So even if the actual blue-collar production activity can be rescheduled at zero cost (which it probably can for a large project such as the AWD), there will still be additional costs arising in the production process.

Of course, that does not necessarily mean that the price of the project to the government has to rise. One explanation for the fulsome embrace of the delays by industry is that they were having trouble delivering on schedule and were happy to be cut some slack. So happy in fact, that they were willing to bear the additional cost of an extended production schedule in order to avoid the risk of larger losses due to missed deadlines over the next few years.

On balance therefore, it seems that the latest round of delays to the AWD project were the result of three factors: budget pressures internal to Defence, problems within the project itself, and a yet to be disclosed plan to provide continuity to the domestic construction sector. All of this seems reasonable in the circumstances. But we should not lose sight of the main game; more than four years of AWD availability to the RAN and Australia’s defence have been lost since the approval of the project. Care is needed to ensure that the industry tail does not wag the capability dog.

Mark Thomson is senior analyst for defence economics at ASPI. Print This Post

Print This Post Setting aside the possibility that the government is simply spinning a line on the workforce issue, this means that there is something new being considered by the government for the maritime sector. There are several possibilities:

Setting aside the possibility that the government is simply spinning a line on the workforce issue, this means that there is something new being considered by the government for the maritime sector. There are several possibilities: