Lawmakers return to Washington, D.C. today for an abbreviated session before the Presidential election. While Congress will seek to maintain the status quo over the one-month sitting, funding the Zika response must be at the top of its agenda. Not only must Congress act to respond to the significant shift in the epidemic in the US over the summer, but it must fulfil the US’s reputation as a leader in global health.

August marked a shift in the Zika epidemic. While the US has

over 2,600 reported travel associated cases of Zika, officials are now reporting 49 locally acquired Zika infections, acquired in two neighbourhoods of Miami, Florida: Wynwood and Miami Beach. These recent cases are particularly significant, meaning that local mosquito populations are infected with and transmitting the Zika virus.

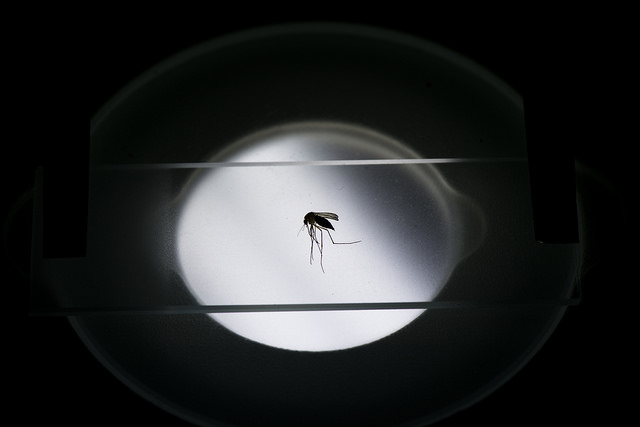

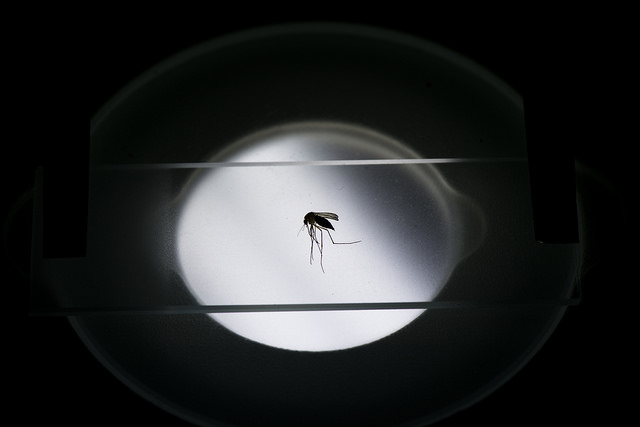

While the mosquitoes that carry Zika—the

Aedes aegypti and

Aedes albopictus—

are present in at least 30 US states, further clusters of cases in the US are

expected to be relatively small and limited. Hawaii, Texas and Florida—where the mosquitoes that transmit Zika are active all year around—remain the main concerns. The virus can also be sexually transmitted, posing a further risk to pregnant women if their partner travels to an area of active transmission.

Despite the shift from travel-associated to locally-acquired infections over the US summer, Congress is yet to approve funding for America’s Zika response. Hillary Clinton recently made

a campaign stop at a medical clinic in Wynwood to call upon Congress to immediately take steps to pass funding for the Zika response: funding desperately needed not just for Miami, but for other US cities likely to have local transmission of Zika. As Secretary Clinton noted, the outbreak in Florida ‘is really the canary in the mine’.

In February, President Obama

submitted to Congress an emergency supplemental funding request of US$1.9 billion, to fund the Zika response. More than five months later, Congress has continued to balk at approving this request, frustrating the US’s domestic and regional response, including vector control (such as mosquito spraying) and the development of a possible vaccine.

Before the summer break, attempts by the House of Representatives and Senate to pass amended versions of the funding bill descended into politicking, including so-called “poison pill” provisions to prevent any monies going to Planned Parenthood—particularly troubling given the specific risk of sexual transmission of Zika and

its disproportionate impact on foetuses and women’s reproductive rights.

Now, with Congress returning, it must avoid the similar delays that plagued earlier negotiations. Passing funding isn’t simply a matter of public health, but one of ethics and justice. Pregnant women, particularly those in lower socio-economic status groups in the southern US, are at an increased risk of both contracting Zika and bearing a disproportionate burden from Zika. In low socio-economic areas, houses may be less likely to have air conditioning or appropriate window and door screening, highlighting the importance of government-led public health measures, such as insecticide spraying and removal of stagnant water that serve as breeding grounds for mosquitoes. Women in low socio-economic areas are also less likely to have sufficient access to reproductive health services, including contraception, abortion, and maternal and child healthcare. In addition to the potential physical and emotional distress associated with a Zika infection while pregnant, the CDC

estimates the costs of raising a child with Zika-associated birth defects at up to US$10 million per case: a significant issue for a country without universal health care.

The development of a vaccine is a fundamental part of the ongoing and future Zika response. The NIH has

announced that it has commenced a clinical trial of a possible Zika vaccine. If successful, a phase two trial to assess the vaccine’s efficacy in protecting against Zika infection and associated birth defects can begin in Zika-endemic countries by early 2017. This research came dangerously close to ending in August due to a lack of funding forcing the Obama administration to

divert US$81 million from existing cancer and diabetes research, antipoverty and health care programs in order to fund Zika vaccine development. It’s a perverse outcome driven by desperation as the pressing need for a vaccine grows.

This followed previous extraordinary measures in April when Congress’ ongoing failure to approve Zika funds forced the

White House to divert US$589 million from Ebola recovery and prevention funding to the Zika response. That move risks making the US ultimately more vulnerable to infectious disease threats. The failure to develop and secure strong public health systems in developing countries—especially those with ongoing flare-ups such as for Ebola-affected countries in West Africa—risks the health, safety and security of the United States. Unsustainable and reactionary reallocation of money from one infectious disease outbreak to another undermines global efforts to ensure surveillance, detection, response and control strategies.

The US Congress’ failure to respond to the Zika pandemic isn’t simply a dereliction of its duty to protect US citizens, but it also significantly undermines the country’s role as a leader in global health and weakens global health security. Before more pregnant women and their foetuses are put at risk, it’s paramount that the US Congress uses this month to immediately pass sufficient and appropriate funds for the Zika response.

Print This Post

Print This Post