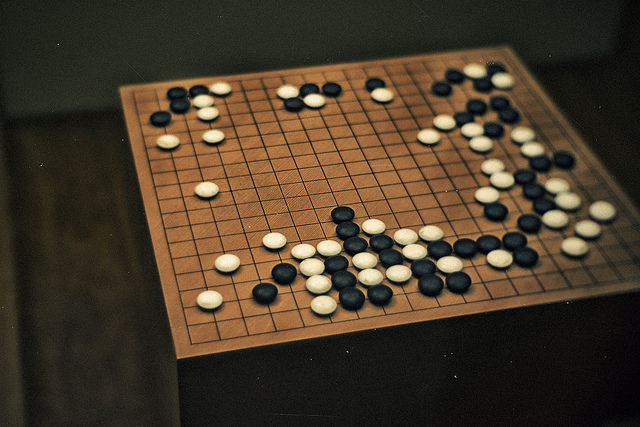

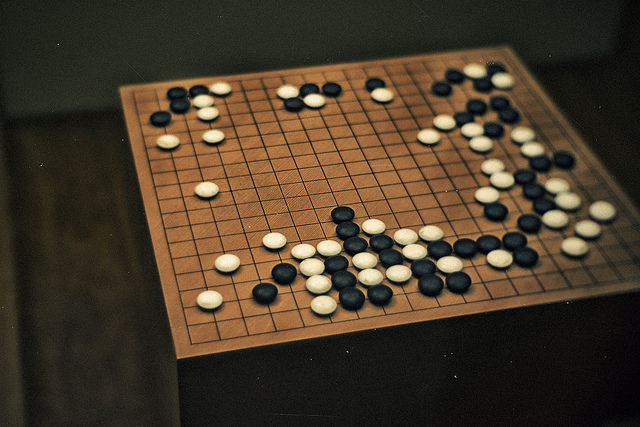

The contest for the future of the Asia–Pacific is often treated by analysts and participants as a two-player game. The US and China are trying to ‘lead’ and the ‘winner’ will be the country that can ultimately control the most rules and other players in the system at some unspecified point in the future. For example, here’s the usually excellent commentator Evan Feigenbaum:

This board game style picture captures some big and important parts of the present competition. But it also imposes a tactical emphasis that isn’t always ideal. Namely the jostling between the two main countries to decide and dictate the way ahead.

The Trans-Pacific Partnership is a classic example. It was started by Brunei, Chile, New Zealand, and Singapore as the Trans-Pacific Strategic Economic Partnership Agreement in 2005. Once the US decided to negotiate entry in 2008 however, it was soon treated as a US initiative for the region. For the Obama administration the TPP became a way to show that the Pivot/Rebalance was more than just a military effort. For analysts it became a test of American leadership, in contrast to China’s ‘One Belt, One Road’ plans.

With an intransigent US Congress and both Presidential candidates now against the treaty, many see the likely failure of the TPP as evidence of a failure of US leadership in the Asia–Pacific. In turn, China is seen as having achieved a victory. It didn’t have to be like this.

What the board game picture obscures is that the real contest isn’t dependent upon the strength of American ‘leadership’, but the dispersal of its values. So long as most of the region sticks to basic capitalist, pluralistic, institutional and democratic norms (in that rough order of priority), then China’s ability to challenge American interests will be largely diminished.

It’s no coincidence that the most capitalist region in the world (Asia) is the one most comfortable with US presence. Meanwhile more protectionist areas such as the Middle East or Latin America (which have also seen extensive US ‘leadership’) still seethe at the idea of America as a regional player.

What matters for the US isn’t whether it’s the one that sets the rules, but rather whether the rules are set in ways that suit it.

Even our habit of calling ideas such as markets and institutions ‘US values’ is somewhat of a reversion to the board game picture. The opening up of Asia to capitalism owes as much to the actions of domestic actors in each country, and regional actors such as Australia, Singapore, South Korea and Japan as it does to the United States.

These partners of the US played vital roles helping to spread the norm of trade liberalisation over the last few decades. They established institutions, they made good faith cuts to their own barriers, they persuaded, negotiated and pushed hard to bring the rest of the region on board.

The US was a clear beneficiary of the spread of open market economies in Asia. Not only was it able to gain wealth from the new markets, the change also helped to soften any threat posed by a ‘unipolar’ Washington in the 1990s, while increasing the importance of the US to the region ever since.

US allies and partners are thus its greatest resource in the endurance of an Asian region which supports American interests and concerns.

As I’ve previously written, building up the military capabilities of its partners ought to be the US’s predominant focus.

In return, these states need to do far more to ensure the dispersal of values and ideas which support a long-term US presence. Rather than providing reassurance or loyalty—as Australians are want to do—we should do more to ensure the region suits American interests. Foremost among those is the capitalist orientation of the region.

While there’s

still a chance for the TPP to pass in a lame duck session of Congress, work must now begin on its successor: one that’s started by states in Asia, which focuses on the concerns of Asia, and which, even if the US does later join, is always talked about and presented as an Asian arrangement.

Australia can play a crucial role here. We have a

long and proud history of supporting trade liberalisation, for economic and strategic reasons. In the 1990s we wisely switched to Preferential Trade Agreements, which have kept the deals coming. But that well is running dry. And it has tended to shift the emphasis to questions of Australia’s immediate gains, rather than long-term regional openness.

As Bob Hawke

wrote in his memoir, ‘increasingly foreign policy

is trade policy and trade policy

is foreign policy’. A common path to Australia’s concerns for prosperity (via more trade) and security (via an enduring US presence) may thus lie in the creativity and ambition of our trade policy.

Play time is over.

Print This Post

Print This Post