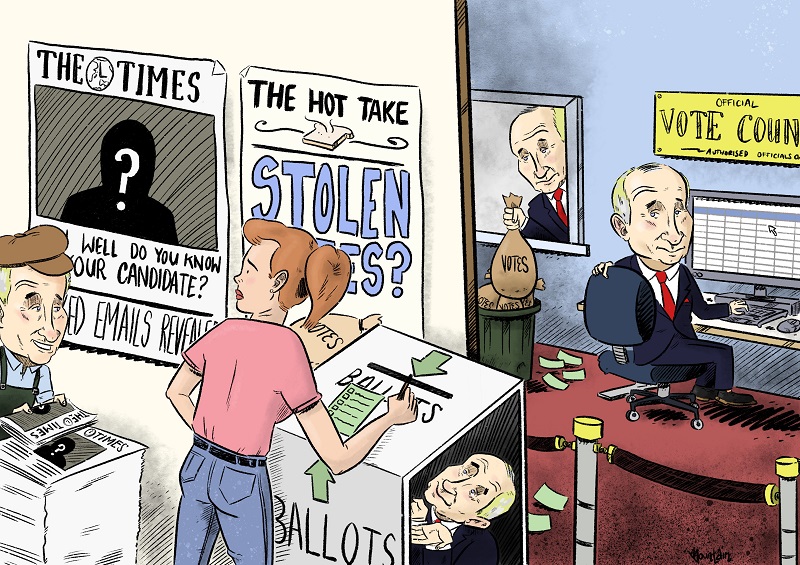

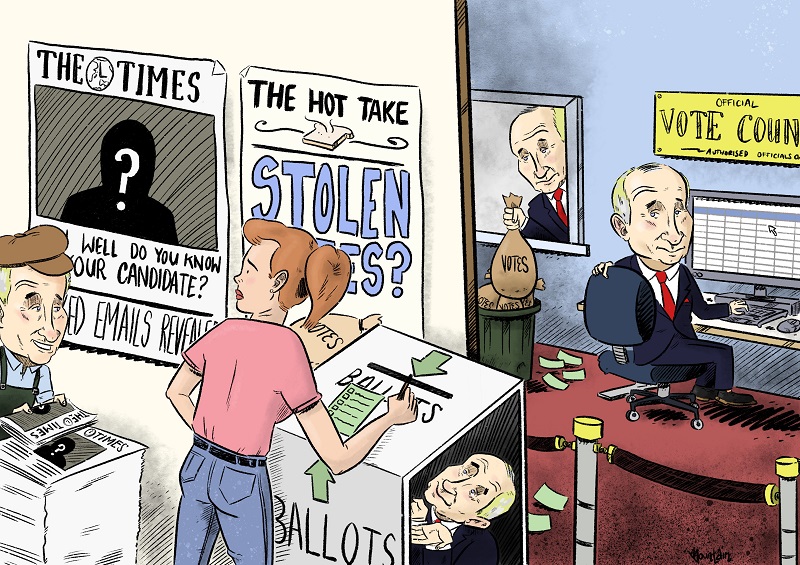

Cyber-enabled election interference has already changed the course of history. Whether or not the Russian interference campaign during the US 2016 federal election was enough to swing the result, the discovery and investigation of the campaign and its negative effects on public trust in the democratic process have irrevocably shaped the path of Donald Trump’s presidency.

Covert foreign interference presents a clear threat to fundamental democratic values. As nations around the world begin to wake up to this threat,

new research by ASPI’s International Cyber Policy Centre has identified the key challenges democracies face from cyber-enabled election interference, and makes five core recommendations about how to guard against it.

ICPC researchers studied 97 national elections which took place between 8 November 2016 and 30 April 2019. The 97 were chosen out of the 194 national-level elections that occurred during the time period because they were held in countries ranked as ‘free’ or ‘partly free’ in Freedom House’s

Freedom in the world report.

The study focused on cases of cyber-enabled interference (for example, social media influence campaigns or hacking operations). It didn’t include offline methods of foreign influence, such as large donations. Foreign interference was measured according to the yardstick provided by former prime minister Malcolm Turnbull when he

described ‘unacceptable interference’ as ‘foreign influence activities that are in any way covert, coercive or corrupt’.

Of the 97 elections and 31 referendums reviewed, foreign interference was identified in 20 countries: Australia, Brazil, Colombia, the Czech Republic, Finland, France, Germany, Indonesia, Israel, Italy, Malta, Montenegro, the Netherlands, North Macedonia, Norway, Singapore, Spain, Taiwan, Ukraine and the US.

Interference was overwhelmingly attributed to Russia or China. The research found a strong geographical link between attributed sources of foreign interference and target countries. Interference in 15 of the 20 countries was attributed to Russia, primarily in Europe and South America, while Chinese interference campaigns showed a strong focus on the Asia–Pacific.

The research identified three categories of interference:

- interference targeting voting infrastructure and voter turnout

- interference in the information environment around elections

- long-term erosion of public trust in governments, political leadership and public institutions.

Of the three, direct tampering with voter results is the most disturbing because it overturns the will of the people. Perhaps the most

egregious case took place in Ukraine back in 2014 (a date outside the scope of the ICPC dataset). Just 40 minutes before the election results were due to go live on national television, a virus was discovered on the computer system of the Central Election Commission. The malware was intended to alter the results of the vote to hand victory to ultra-nationalist Right Sector party leader Dmytro Yarosh.

A more subtle method of interference is altering the information environment in which elections take place—thereby illegitimately persuading voters to change their votes themselves, rather than tampering with the vote after the fact.

This kind of interference is by its nature difficult to detect, even for those whose job it is to sniff out fakes and liars. During the interference campaign in the US in 2016, for example, Russian operatives created a fake Black Lives Matter activist. The ‘Luisa Haynes’ persona was so convincing that it accrued over 50,000 Twitter followers, and its tweets were quoted in news stories by the BBC,

USA Today,

Time,

Wired and the

Huffington Post.

The third category is both the most slippery and the most pernicious: the deliberate erosion of trust in public institutions. These kinds of campaigns target key public bodies such as electoral commissions—for example, implying that government officials may themselves be tampering with the vote results. The impact of this type of interference is difficult to quantify, but recent polls by

Pew and

Gallup have found widespread declines in public trust in democracy as a whole.

Defending the democratic process from cyber-enabled interference will be a complex, long-term challenge. The ICPC’s researchers have identified seven steps which policymakers should take to help safeguard against such interference efforts.

1. Targets are limited: respond accordingly

The vast majority of campaigns have so far been attributed to only two primary actors, and their targets are aligned with those nations’ strategic goals. Democracies should calibrate their policy responses to the likely risk, methods and adversary. The US and European states are clear targets of the Russian government; Indo-Pacific nations are targets of the Chinese Communist Party.

2. Build up detection capabilities

More effort is needed to detect foreign interference, including offline and non-state efforts. Because democracies have a natural aversion to government surveillance, a better answer than simply stepped-up government monitoring may be supporting non-profit, non-government initiatives and independent media. These groups can more credibly monitor for interference and more easily engage at the community level.

3. Fund research to measure impact and measure the effectiveness of education campaigns to address public concerns

Governments should fund research to develop better ways to measure the impact of foreign interference to allow for a more informed decision on resourcing efforts to counter it. There’s a lack of empirical data on the impacts of foreign interference and the effectiveness of various attempts to combat it, such as fact-checking services.

4. Publicly fund the defence of political parties

Political parties and individual politicians are clear targets of foreign adversaries. With their shoestring budgets and the requirement to scale up dramatically during election campaigns, they’re no match for the resources of sophisticated state actors. There’s a strong public interest in preventing foreign states from being able to exploit breaches of political parties and individual politicians to undermine domestic political processes. Democratic governments should consider public funding to better protect all major political parties and to step up cybersecurity support to politicians.

5. Impose costs

Democracies need to look at better ways of changing the risk calculus and imposing costs on adversaries. Democracies should consider concerted joint global or regional action, as well as more traditional approaches such as retaliatory sanctions. Legislation may also be needed to make it more difficult for adversaries to operate.

6. Look beyond the digital

Russian interference is detectable, if not immediately, then often after the event. This has generated a natural focus on Moscow’s methods and activities. However, there are many more subtle ways to interfere in democracies. Research like this study, which focuses on digital attack mechanisms, also misses more traditional and potentially more corrosive tactics, such as the provision of funding to political parties by foreign states and their proxies and the long-term cultivation of political influence by foreign actors. States, particularly those in the Indo-Pacific, should be attuned to these types of interference and make preparations to prevent, counter and expose them.

7. Look beyond states

Troubling public perceptions of democracy are unlikely to be explained by foreign interference alone. Foreign interference may, however, magnify or exploit underlying sources of tension and grievance. A thorough response by government and civil society needs to consider a wider set of issues and threat actors, including trolls working for profit, and the health of the political and media environment.

Print This Post

Print This Post