Even the most hard-headed of strategic analysts would have to concede that we are now facing a direct and very real threat to our individual and collective security of a sort and severity that we have not seen before in our lifetimes. Ironically enough, it

turns out that there really was a threat from China after all, just not the one we have spent billions of dollars preparing for.

The old cliché about generals—not to mention policymakers and their advisers—has never looked more apt: they really have been readying themselves to fight the wrong war. None of the exotic and eye-wateringly expensive military hardware that strategic types claim is vital to keep us safe can protect us from an invisible enemy that isn’t easily deterred.

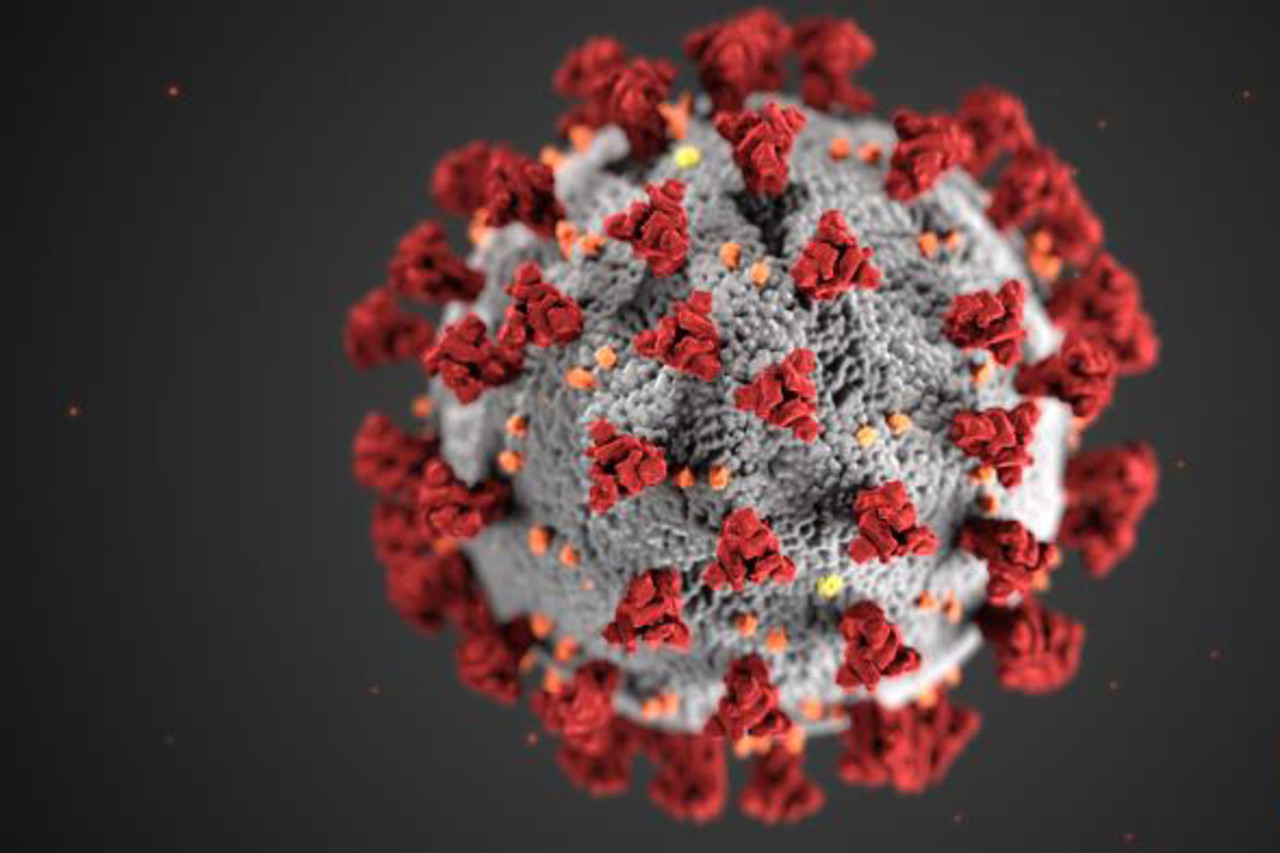

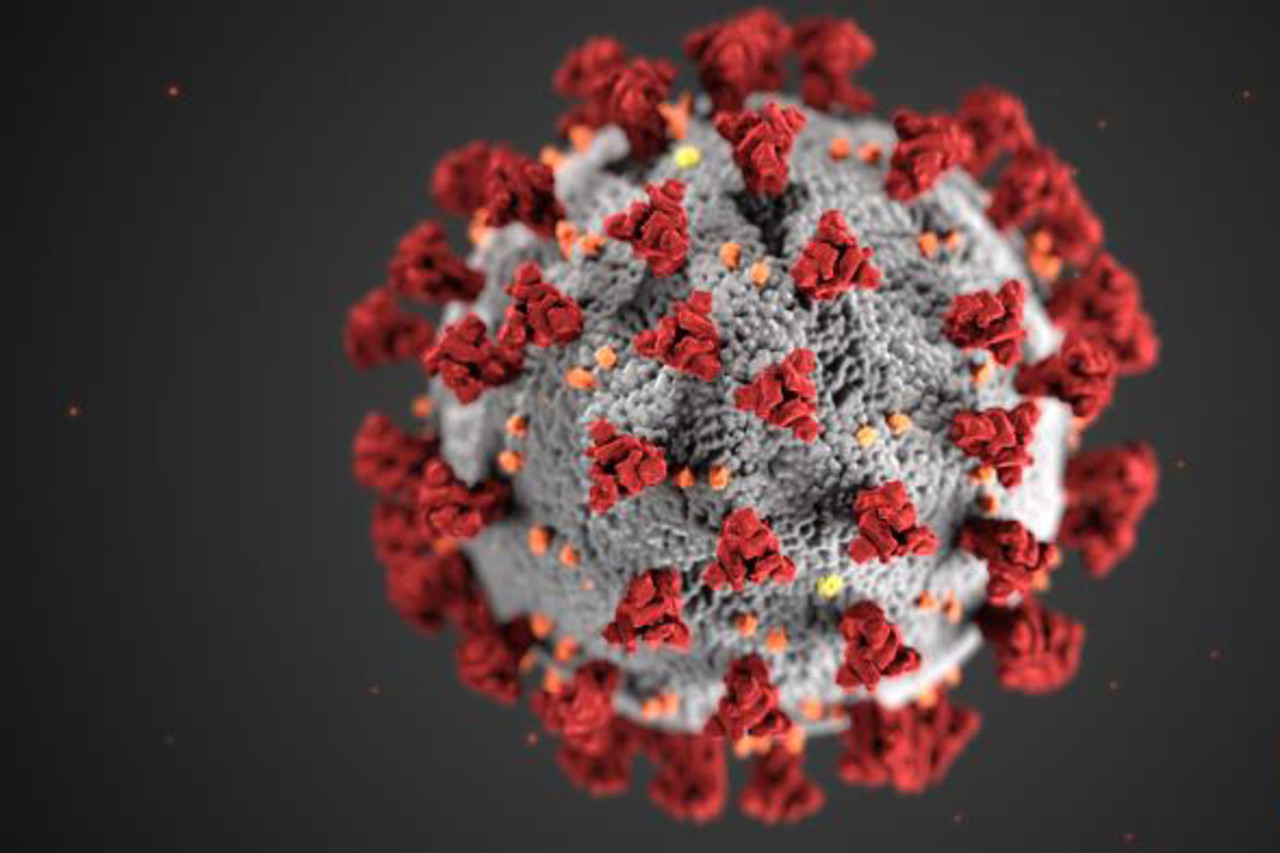

While there may still be some debate about the exact origins of Covid-19—outside of the ranks of some of the more conspiratorially minded denizens of the Twittersphere, at least—it seems relatively uncontroversial to suggest that like other new viruses it is a product of

changes in the natural environment. As with climate change, it is partly a consequence of human activity and our collective impact on the biosphere.

A still surging global population is causing new forms of interaction between people and animals, allowing pathogens to

cross the species barrier with devastating consequences. Ebola, SARS and avian influenza all seem to have had similar origins, and all went on to kill human beings in significant numbers. They were not, however, on the apocalyptic scale threatened by Covid-19, nor did they threaten the privileged populations of most of the Western world.

Nevertheless, these earlier episodes ought to have provided the proverbial wake-up call and warning for political and strategic elites everywhere. Rather predictably, however, potential lessons went unlearned and little effort was made to prepare for the possible outbreak of a pandemic that might prove more pervasive, virulent and deadly.

Even when the novel coronavirus crisis was clearly gathering pace in China, policymakers in the West, predictably

led by US President Donald Trump, remained in furious denial about the scale and immediacy of the dangers. Australia’s response is gradually ramping up, but it is

still proving difficult for policymakers to grasp the enormity of the threat and to take actions that will undoubtedly transform the Australian way of life.

It’s easy to be wise after the event, no doubt. But many people have been warning of the risk of a global pandemic for years, with

no perceptible impact on public policy. The lack of preparedness of health systems around the world is being brutally exposed, and not just in the so-called developing world either.

The United States has the

worst of all possible worlds: a preposterously expensive and shamefully inadequate health system, especially for the swelling ranks of the working poor. America’s political and economic system may be thrown into sharp and unflattering comparative relief with China’s, which has demonstrated what determined, albeit unaccountable and authoritarian, leadership can do.

The Covid-19 pandemic consequently is providing the biggest shock to the international order since World War II. There’s nothing quite like the threat of one’s imminent demise or the overnight evaporation of economic security to focus the attention. No doubt life will go on, but it may never be quite the same again, and people will understandably want to know why it happened and why we weren’t better prepared.

Exactly the same questions could and should be asked about climate change. What makes this crisis different, of course, is the breathtaking speed with which it has unfolded. In the process it has overturned many of our most deeply held assumptions about the stability and predictability of life in even comparatively well-run polities such as our own.

If this crisis does nothing else, it ought to dramatically bring home to us how deeply interconnected we are with the natural environment upon which we ultimately depend. It is also clear that this is an essentially

interactive process: if we damage or abuse the environment too much, the results of those actions pose not just a niche ethical dilemma for inner-city liberals, but a direct threat to human life everywhere. Wealth and power are no protection, even if they ensure the best medical care money can buy.

Is this the ‘

revenge of Gaia’, as the prominent and controversial environmental scientist James Lovelock predicted in 2006? Perhaps not. But even those who don’t believe that the earth is a ‘whole system of animate and inanimate parts’ locked in mutually constitutive interdependence may have to start thinking about our relationship to the planet in new and more sustainable ways.

If we can’t organise ourselves and lighten our growing burden on the natural world, nature may do it for us. If that’s not a security dilemma, it’s hard to know what is.

Print This Post

Print This Post