The gathering’s theme was ‘Security and Cooperation in the Asia Pacific Region,’ yet the US–China relationship dominated. The symposium run by the China Institute for International Strategic Studies was free of academic mumbo-jumbo. The sessions, at which Bob Hawke and I were the two Australian participants, seemed under a spell cast by Presidents Barack Obama and Xi Jinping. Even the Southeast Asian voices adopted the Eagle–Dragon focus, though not willingly. Said a Malaysian scholar: ‘Why do you Chinese engage with the US all the time and never with us, especially at the military level? The result is we don’t really know where China is headed.’

The gathering’s theme was ‘Security and Cooperation in the Asia Pacific Region,’ yet the US–China relationship dominated. The symposium run by the China Institute for International Strategic Studies was free of academic mumbo-jumbo. The sessions, at which Bob Hawke and I were the two Australian participants, seemed under a spell cast by Presidents Barack Obama and Xi Jinping. Even the Southeast Asian voices adopted the Eagle–Dragon focus, though not willingly. Said a Malaysian scholar: ‘Why do you Chinese engage with the US all the time and never with us, especially at the military level? The result is we don’t really know where China is headed.’

The Chinese were frustrated that their goals came across as unclear. But ‘peace and development’ is a vague definition of a rising superpower’s aims. The real goal was implied by a smart Chinese military officer: ‘Security mechanisms in the region have the mark of the Cold War and are exclusive and not conducive to trust’. The message is clear: China wants US security pacts in the Pacific ended or weakened. Kevin Rudd will find Beijing tougher on this matter now than during 2007–2010.

The Chinese play a game of the pot calling the kettle black over criticisms by the US. When Defense Secretary Hagel expressed ‘disappointment’ with China’s role in Edward Snowden’s departure from Hong Kong, the Chinese said they were equally ‘disappointed at NSA aggression’ against China revealed in Snowden’s disclosures. Over the riots in Xinjiang last month, the Chinese also turned criticism back at the US; Washington should not fret at Chinese police response in China’s far west, they say, because the rioting Muslims are trying to ‘overthrow the Beijing government’ and Americans ought to condemn these ‘terrorists’ as they do terrorists in Boston or New York.

Yet there’s an element of shadow boxing to this game of pot and kettle. The Beijing government is certainly argumentative, but its actual policy towards the US is more cautious than the rhetoric on these two issues may suggest.

Interestingly, a Chinese historian said that fascist powers’ overreaching in the 1940s taught China a lesson, as did the Soviet Union’s in various places and the US’s in Iraq and Afghanistan. ‘We will never go that route of overreaching,’ he vowed. ‘The territorial dispute [in the Senkakus] occurs because the outcome of WWII is being disputed,’ said a senior Chinese analyst. Actually, what's being disputed is the lesser place for China implied in the post-WWII alignment of the US and Japan in the Western Pacific. Beijing is challenging this 65-year-old status quo. It’s a delicate dance. A Chinese participant reasoned: ‘The Asia Pacific is big enough to accommodate US, China, Russia and other countries.’ Like other Chinese at the symposium he seemed reluctant to utter the word ‘Japan’.

The South China Sea disputes weren't probed in detail (no Philippines delegate was present) but a Vietnamese purred: ‘Major powers have a special responsibility to handle the suspicions of smaller countries’. The Indonesian military speaker took an indirect approach, rich with a hint to Beijing, pointing out Jakarta’s success in establishing good relations with East Timor despite the difficult origins of the mini-state and Jakarta's patience in calming the situation in Aceh Province.

India only came up when I mentioned that ‘Indo-Pacific’ is Canberra’s favoured regional label, and in a direct assault by the female Pakistani who warned: ‘Please be aware the rise of India to real power would bring to the fore manifold territorial disputes in South Asia between India and its neighbours.’ She may be correct—China’s rise has certainly produced heightened disputes in the Chinese seas.

According to several Chinese, two models of leadership exist in the region, 'two ways of leading: hegemony and conciliation’. Former Prime Minister Bob Hawke expressed a view many Australians would accept: ‘We want America to stay in Asia on a basis that China is willing to accept, and we want China to accept that America should remain as a major power in the region’.

The idea of America and China ‘sharing’ leadership in the Asia Pacific is fine, but sharing comes in many forms. The US and the USSR shared a fear (‘mutual assured destruction’) that in the end kept the peace. Shared American and Chinese values would make shared leadership easy, but a values gap exists and partial overlap of interests is all we can expect. Washington and Beijing could find overlap on Korea, by replacing the futile disarmament talks with a fresh agenda for Korean reunification, orchestrated and guaranteed by China and the US. Perhaps the TPP offers another chance. It is

not exclusive (despite claims to the contrary), it could be conducive to trust, and Chinese membership in TPP would be a boon for China’s internal reformers—as happened when Beijing joined the WTO.

There's a precedent—Mao and Nixon found an overlap of interests in 1972, despite no pre-existing trust, no trade, and no diplomatic relations between the two when Nixon landed in Beijing. The mantra of trust is overdone. Trust comes when results accrue, not through smiles and banquets. Beijing and Washington began to trust each other in the 1970s after seeing the electric impact of the Mao–Nixon handshake on Moscow.

Today the Chinese and American view of each other is ambivalent. This could imply prudence on both sides, not ruling out real future cooperation. Less hopefully, it could mean the trajectory of China’s rise is so stark that neither Washington nor Beijing is quite sure of the next plateau for the relationship.

Chinese ambivalence exists not because the leadership is split toward the US, but due to a conscious

yin-yang stance with a long pedigree. It’s worth nothing that Mao said in public in 1970, as he and Nixon were rubbing their hands ready for their startling rapprochement that the US 'which looks like a huge monster, is in essence a paper tiger, now in the throes of its death-bed struggle’. Today Beijing pushes against Japan, India, Vietnam, Philippines and other US friends, yet it knows cooperation with Washington is in its best interests. Nibbling away, it seeks to lower the price it will pay for that inevitable cooperation. This might be a rational strategy at a time when the US is led by a diffident president.

At a meeting Hawke and a few of us from the symposium had with Yang Jiechi in Zhongnanhai, the top foreign policy figure in the government told us 'China is going to be more active in the Middle East. America has failed in this region. China will try'. But equally prominent in Chinese statements is alarm that this same ‘failed’ US flexes its muscles to China’s disadvantage in its own backyard. The contradiction is revealing. Beijing is aware of US latent strength but uncertain about US will. Isn’t nearly everyone?

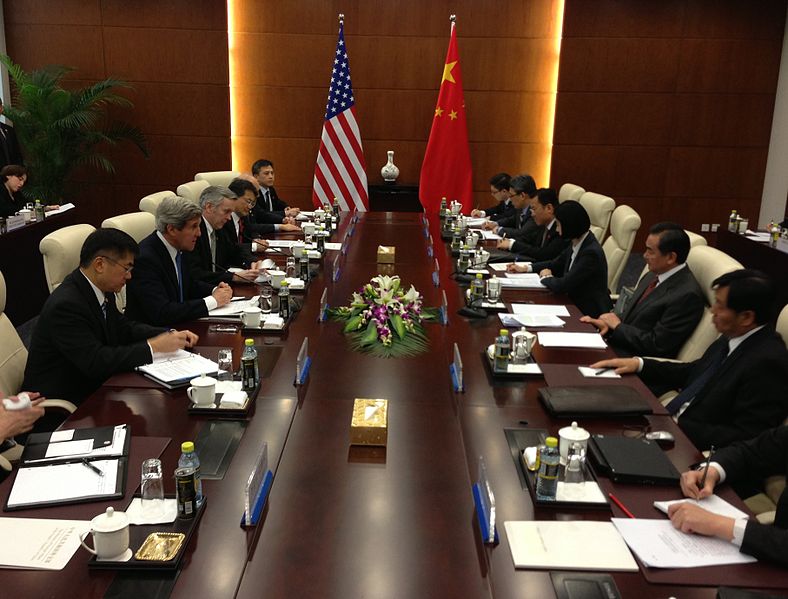

Ross Terrill is an Associate of Harvard’s Fairbank Centre for Chinese Studies, and author of the recent ASPI paper Facing the dragon: China policy in a new era. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Print This Post

Print This Post The gathering’s theme was ‘Security and Cooperation in the Asia Pacific Region,’ yet the US–China relationship dominated. The symposium run by the China Institute for International Strategic Studies was free of academic mumbo-jumbo. The sessions, at which Bob Hawke and I were the two Australian participants, seemed under a spell cast by Presidents Barack Obama and Xi Jinping. Even the Southeast Asian voices adopted the Eagle–Dragon focus, though not willingly. Said a Malaysian scholar: ‘Why do you Chinese engage with the US all the time and never with us, especially at the military level? The result is we don’t really know where China is headed.’

The gathering’s theme was ‘Security and Cooperation in the Asia Pacific Region,’ yet the US–China relationship dominated. The symposium run by the China Institute for International Strategic Studies was free of academic mumbo-jumbo. The sessions, at which Bob Hawke and I were the two Australian participants, seemed under a spell cast by Presidents Barack Obama and Xi Jinping. Even the Southeast Asian voices adopted the Eagle–Dragon focus, though not willingly. Said a Malaysian scholar: ‘Why do you Chinese engage with the US all the time and never with us, especially at the military level? The result is we don’t really know where China is headed.’