Recognition among Western governments of the scale of death and dispossession in Gaza has been widely accompanied by references to the need to return to a two-state solution to the Israeli–Palestinian conflict.

It’s a comforting sentiment. It was the default political answer in the United Nations to an intractable problem in the late 1940s. From the 1970s, it set an ambitious and positive framework for discussion of Middle East policy in Western capitals and, eventually, in the Arab world.

But it has no connection to contemporary realities. At best, the idea of two states has become, once again, an idea long ahead of its time.

A succession of Israeli prime ministers from the right has sought consistently to ensure that no Palestinian state would eventuate in what they call Judea and Samaria. Zionist leader Ze’ev Jabotinsky’s ideal of a metaphorical ‘

iron wall’ to crush Palestinian irredentism has long been their guiding principle.

The idea of a Palestinian state being created alongside Israel always ran counter to the Likud vision of Israel extending from the Mediterranean to the Jordan River. (Indeed, a song popular among Likud supporters used to go further: harking back to Churchill’s creation in the 1920s of the Hashemite state east of the river, at the expense of Zionist wishes, it said: ‘The Jordan has two banks, and both of them are ours.’)

Even the Israeli withdrawal from Gaza in 2005 was intended to

freeze the peace process in place.

Twenty years ago, support on the Israeli left for a two-state approach collapsed, gutted by terrorist violence from Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad, and Palestinian National Authority (PA) president

Yasser Arafat’s failure to exercise the leadership required to quell immediately the outbreak of the second intifada in late 2000.

Coming in the aftermath of the failure of the Camp David negotiations in mid-2000, the bloodshed among Israelis that followed the return to large-scale violence traumatised Israel. Hamas, Iran and Iranian proxies, Saddam Hussein and Islamist terrorists across the Arab and Islamic world rejoiced and postured in it.

At the same time, nationalist and hardline religious parties associated with the Jewish settler movement, enjoying significant financial support from elements of the Jewish diaspora and an absence of countervailing political pressure, and dedicated to achieving perpetual Israeli rule over the West Bank, flourished.

Israel was content, unwisely, to stand by as Hamas took full advantage of the steadily diminishing political strength of its secular rival. It said it had no partner for peace, as Hamas entrenched itself in Gaza and the PA, sclerotic, authoritarian, self-indulgent and limited in its capacity to respond to settler pressure, lost its popular appeal.

The horrific violence of the despicable Hamas attack on 7 October has taken that political trajectory in Israel to a new level. Irrespective of whether Benjamin Netanyahu survives in power in the aftermath of Gaza, voices arguing for Palestinian self-determination will be marginal to the mainstream of Israeli politics for a generation, at least.

On the Palestinian side, long before 7 October it was evident the paradigm of Palestinian politics had shifted. Support for a two-state approach has collapsed.

Fatah, self-indulgent, corrupt and unwilling to do the hard yards of election campaigning, lost to Hamas in Gaza in 2006. It was crushed by Hamas when it attempted a coup in 2007.

Meanwhile, Israeli intransigence; settler violence in the West Bank; the loss of political authority on the part of

Mahmoud Abbas; the contempt of Palestinians for the role played by the PA in meeting Israel’s security demands and destructive military and settler incursions; US promotion of normalisation between Israel and Persian Gulf Arab states, without addressing the Palestinian issue as an essential part of that process; and the emergence of West Bank urban militant groups defying the PA all combined to deadly effect.

Hamas maintained its staunch opposition to a two-state solution, although for external consumption its political wing in Qatar clouded its stance in ambiguities. It presented itself, however improbably, to a generation of Palestinians who had grown up under occupation as a viable, authentic Palestinian alternative to the struggling PA.

It promoted calls for the return of refugees from Gaza that pointlessly sacrificed young Palestinian lives. It carried its posturing to the point of inserting itself, through indiscriminate rocket attacks on Israel, into the struggle for the future of Palestinians in East Jerusalem. It mocked the PA for its adherence to the formal obligations into which the Palestine Liberation Organization entered with Israel, seeking a negotiated settlement.

Its mainstay was, and remains, its role as a symbol of and force for resistance to occupation.

We now face the reality that without an Israeli commitment to—and realistic political prospect of—ending the occupation, and without a determined Israeli effort to address those crucial issues behind the PA’s demise, there will be no credible Palestinian partner to engage in negotiations to arrive at a Palestinian state alongside Israel.

Outsiders cannot create a negotiation in a political vacuum, even in the realm of track 2 diplomacy.

A factor further sealing the two-state solution’s demise is the shift in Israel’s strategic approach, since 7 October, from deterrence and measures to regulate the conflict. Previously, Israel was content to ‘mow the grass’ and perhaps to deepen divisions between Hamas and its Fatah rival. Now it is seeking regime change.

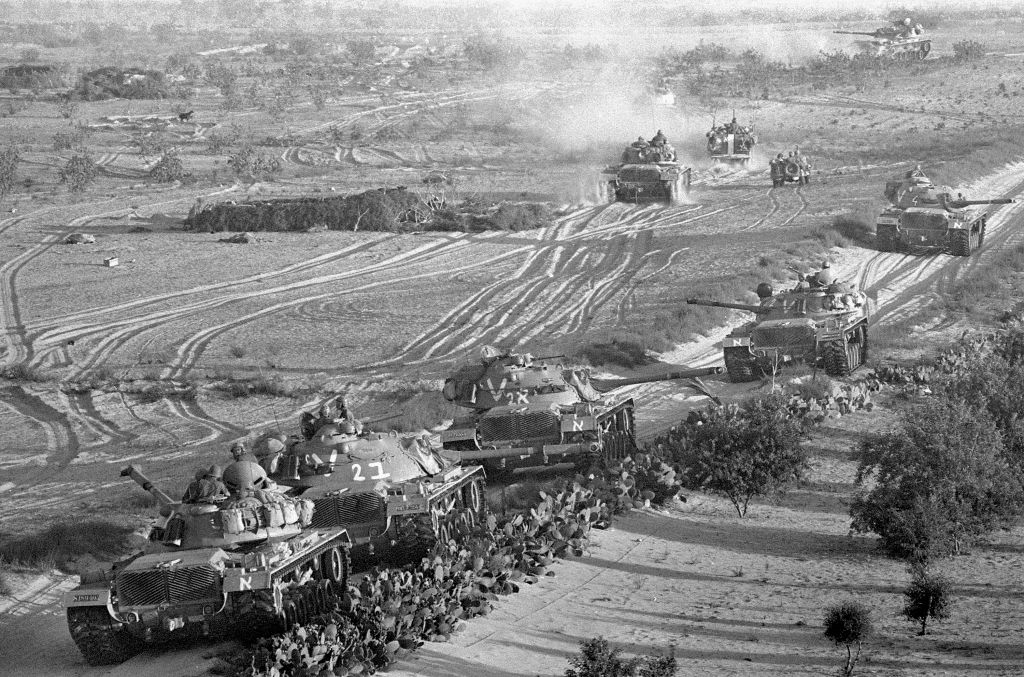

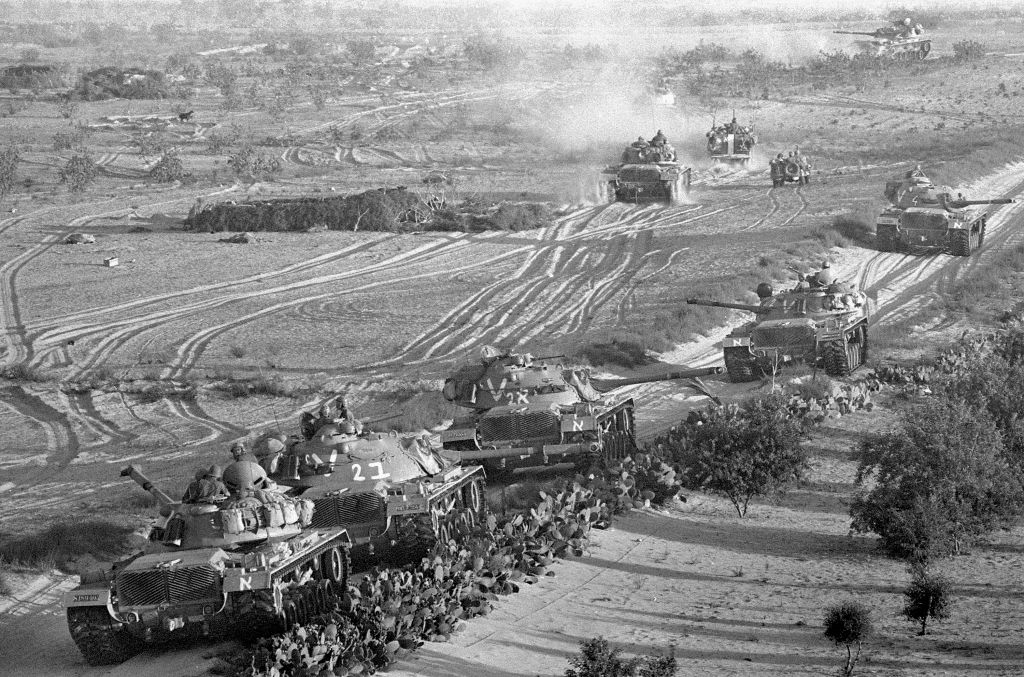

Where regime change has been tried elsewhere in the Arab world (Suez in 1956; Lebanon, 1982;

Iraq, 2003; Syria, 2011–2015) it has failed abysmally, not least because of an absence of clear and realistic political objectives and credible strategies for bringing them to fruition.

Slogans aside, Israel has yet to articulate either its political objectives in Gaza or its intended means to achieve them. Instead, it has been left to the United States to begin formulating ideas for an approach to follow the military campaign.

Secretary of State Antony Blinken and some prominent voices in the US think tank community have spoken of the desirability of an

‘effective and revitalised’ PA resuming control of Gaza—without identifying why the PA has reached its current nadir of political and moral authority among Palestinians.

The reasons for that decline are inextricably connected to the Israeli occupation and the PA’s failure to protect the security and dignity of Palestinians under Israeli control.

Those factors won’t change unless there’s a wholly unexpected shift in the direction of Israeli politics. Instead, it’s

questionable whether the PA will survive its own loss of credibility if Israeli pressures on Palestinians in the West Bank and East Jerusalem continue unchecked.

Blinken has also referred to the possibility of ‘other temporary arrangements that may involve a number of other countries in the region’ and ‘international agencies that would help provide for security and governance’.

The notion that such arrangements would be temporary defies regional experience. The

UN has been in southern Lebanon for four decades.

More importantly, though, it is based on a problematic assumption that a reluctant Egypt, or some other Arab country, could be induced to become, in effect, the security force in Gaza.

No doubt the Egyptians, if they could be pressured and persuaded to assume such a role, would ruthlessly deal with Palestinian militants. They have crushed dissent and subversion at home, including in the Sinai.

But Egyptians across the board are deeply supportive of the Palestinians and hostile towards Israel. And the popular memory of Egypt’s disastrous military intervention in Yemen in the 1960s still runs deep.

Moreover, Israeli officials

have indicated that they expect to maintain the capacity to intervene militarily again in Gaza whenever they identify security risks.

Israel has maintained that approach in West Bank cities including Nablus and Jenin and other urban areas supposedly under PA control. Israel won’t rely on others to deal with those risks.

Once again, however, the conflict’s paradigm has changed.

It would be folly, now, in contemplating the possibility or desirability of creating an international security force, to underestimate the enduring impact on Palestinians, in Gaza and beyond, of the sheer magnitude of the deaths of children and other non-combatants, and the loss of homes for a significant proportion of the population.

It doesn’t matter to Palestinians that Israel insists it isn’t targeting civilians. It is not relevant to dying and injured Palestinians that Hamas, in its unwanted and unspeakably evil actions, caused the loss of their futures. They could not prevent what it did, even if they’d wanted to.

Palestinians are losing their children, their families, their homes and their dignity. They believe the US could prevent that from happening but has chosen not to. They see Western (and Arab) double standards where their lives are concerned.

Against that background, any Arab or other external force in Gaza that failed to resist further Israeli incursions with military force would be damned in Palestinian eyes, just as the PA in the West Bank has been deemed to be an accomplice of the Israeli occupation.

The Egyptian leadership is savvy enough to appreciate those risks. They are committed to the continuation of peace with Israel. And they would know that the costs of occupation, and the security and political challenges of suppressing popular frustration and demands for revenge, among not only Palestinians but much of Egyptian society as well, would, at some point, make an Egyptian occupation of Gaza unsustainable.

Aid will begin to flow from Western countries and the Gulf when the conflict winds down. In due course there will probably be some sort of UN and international coordination mechanism for reconstruction of housing and the

restoration of education, health and medical services in Gaza.

Hamas and its militant counterparts will use that reconstruction effort to rebuild their capacity, drawing on support from around the Arab and Islamic world, and Iran.

The result of the current assault, and its most likely aftermath, will not, therefore, be a rejection of Hamas. Unless the occupation of Palestine ends, which is not in prospect, the aftermath will most probably be the emergence of Hamas Mark 2, more violent, more authoritarian and ideologically driven, and possibly more globally focused than before.

Hamas will not lose the will to fight. Nor will the Palestinian victims of its actions and the Israeli response insist, to any meaningful effect, upon an end to violence. As on the Israeli side of the equation since the horrors of 7 October, a fundamental line has been crossed.

Western rhetoric notwithstanding, there will be no two-state solution, nor much prospect of meaningful steps being taken towards achieving one. Instead, there will be recurring cycles of violence.

Israel will prevail in those conflicts with the Palestinians until, one day, it doesn’t. And when that day comes, even generations from now, the reckoning will be terrible.

Print This Post

Print This Post