Abe’s recent trips to Southeast Asia show that Japan is turning once again to the region. Abe travelled to Indonesia, Thailand and Vietnam in January — his first foreign tour since his re-election as prime minister.

He visited Myanmar in May, and then Malaysia, Singapore and the Philippines in July. Abe is also set to visit Brunei, Cambodia and Laos in October. While many observers interpret such visits primarily as a strategy to counter China, it can be argued that Japan’s major motive for this diplomacy is a mix of both commercial and strategic interests.

Abe’s Southeast Asia visits are not unprecedented. Japan has turned to Southeast Asia numerous times in the past, evident in foreign policy changes orchestrated by Prime Ministers Sato, Tanaka and Fukuda. Each time Japanese leaders have approached Southeast Asia the main issues have usually involved China, concerns over Japan’s economy, or both. While it was not accompanied by a tour, Japan’s first turn to the region in the post-war period happened in the 1950s under Prime Minister Yoshida. The motive for the turn was mainly commercial, as the Southeast Asian region was seen then as a substitute for the ‘loss’ of the Chinese market after it shifted to a socialist system. Since then, Japanese leaders have consistently attached great importance to its relationship with countries in Southeast Asia. This observation is reinforced by Japan’s huge economic presence in the region in the form of aid, trade and investment, which have grown progressively over the years.

The first three countries that Abe chose to visit in January reflect his intention to maintain these valuable relationships. Among ASEAN member countries, Thailand was the most popular destination for Japanese investment in 2010, followed by Vietnam, while Indonesia has the biggest market among ASEAN member countries. Another reason for these visits was to monitor the disruptive effects of natural disasters on Japan’s regional supply chain; after the flooding in Thailand and the Tohoku earthquake, some Japanese manufacturers have contemplated shifting their operations to Indonesia and Vietnam. Moreover, the third arrow of Abe’s ‘three arrows strategy’ calls for a reform program that promotes private sector investment-led growth. This conforms to the New Growth Strategy launched in 2010, which emphasises the promotion of ‘superior’ Japanese technology, such as railways and water technology. The growing affluence of Southeast Asian societies and the high demand for regional infrastructure are conducive to Japanese leaders ‘peddling’ Japan’s own products and technology, which can be funded through loans and Japanese development assistance.

The strategic component of the visits is also manifested by Cambodia’s and Laos’ inclusion in the itinerary, Abe’s constant reference to ‘shared values’ in his dialogue with regional leaders, and a proposal to promote maritime cooperation, particularly with the Philippines. China’s economic and military assistance to Cambodia and Laos have strengthened bilateral ties and Chinese influence within these countries. The latter was made evident during the July 2012 ASEAN Ministerial Meeting in Phnom Penh, in which Cambodia, acting as chair, opposed the inclusion of the South China Sea/West Philippine Sea issue in the concluding joint statement. Cambodia’s stand was a diplomatic victory for China, which prefers to settle territorial disputes via bilateral talks rather than multilateral forums. This episode also reveals the divisive effect of China’s charm offensive on ASEAN. Great economic dependence by any ASEAN member on China could potentially damage the association’s cohesion and unity in the long run. This possibility leads to the second strategic motivation of Abe’s Southeast Asian tour.

By further strengthening ties with ASEAN members, Japan could help mitigate China’s charm offensive by resorting to a strategy of soft containment. This subtle version of containment is different from the policy used by the United States against the spread of communism during the Cold War. Japan knows that it has nothing to gain by containing China, now its largest trading partner. Instead, this flexible strategy allows both engagement and curtailment of China’s expanding influence. There are two ways by which Japan could achieve this: value diplomacy and institution building. During his dialogue with Southeast Asian leaders, Abe constantly referred to a set of shared values, such as democracy, human rights and rule of law. Abe declared that he ‘wants to emphasise the importance of strengthening ties with [Southeast Asian] countries that share such values’. China could not seek to realise these values, and nor does it have the credibility to pursue them — although if ‘value’ diplomacy works, it may put pressure on China to eventually embrace those values.

Meanwhile, the proposal for strengthened maritime cooperation represents Japan’s desire for long-term regional stability through institution building. During his Philippines visit, Abe reiterated the importance of cooperation on maritime and oceanic affairs. Abe can use this opportunity to take the lead in building institutions for a maritime code of conduct (including a fisheries code). Building maritime institutions in order to reduce tension complements Japan’s strategy, since participation in any form of collective security or military deterrence is constrained by constitutional and other domestic factors.

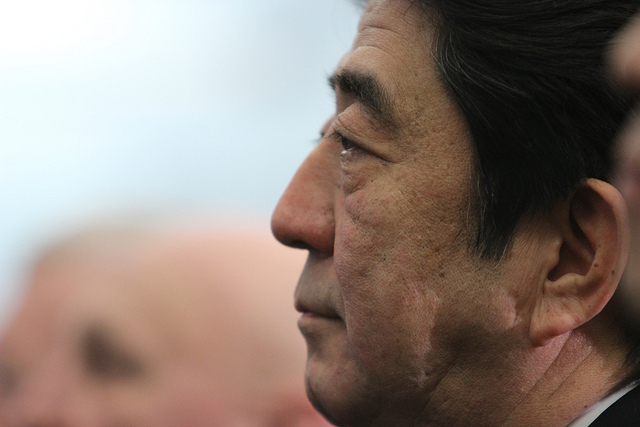

Dennis D. Trinidad is associate professor and head at the International Studies Department, De La Salle University, Manila, Philippines. Image courtesy of Flickr user CSIS.

This post first appeared on East Asia Forum.