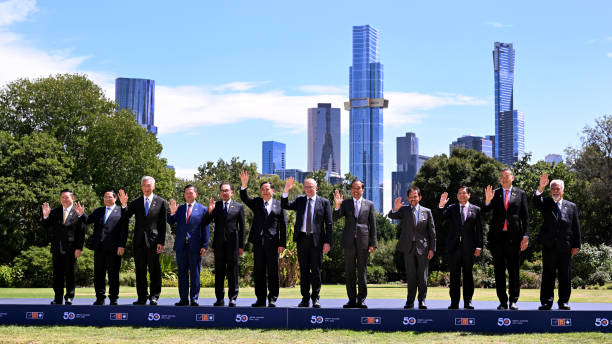

As this week’s 50th anniversary ASEAN-Australia summit wraps up in Melbourne, I would like to offer one simple piece of policy advice to each party to help them strengthen their relations in future from a position of intellectual clarity.

First, for ASEAN, a rigorous parsing of the differences between non-alignment and neutrality could be helpful for articulating Southeast Asian countries’ foreign policy interests more in line with their traditions.

The 11 countries of Southeast Asia, including the 10 ASEAN members and Timor Leste, all belong to the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM). NAM notably originates from an Indonesian initiative to convene the world’s developing and newly independent countries, then mostly from Asia, at a summit in Bandung, in 1955. NAM describes this foundational impulse as a ‘desire not to be involved in the East-West ideological confrontation of the Cold War, but rather to focus on national independence struggles and… economic development.’

The Bandung Principles somewhat loftily specify a commitment to abstain ‘from the use of arrangement of collective defence to serve the particular interests of any of the big powers, (and) abstention by any country from exerting pressures on other countries.’

In Southeast Asia, only the Philippines has continuously maintained a bilateral defence treaty with Washington (since 1951) though it no longer hosts US military bases or forces on a permanent basis. Thailand was a close ally of the US during the cold war and remains a major non-NATO ally to this day. Under various arrangements, Brunei, Singapore and Malaysia all host foreign military forces on a modest scale, none of which has impeded NAM membership or their pursuit of non-aligned policies.

In its heyday, in the 1960s, non-alignment was widely embraced as offering a means for developing states to avoid siding with either the US-led or Communist blocs, and preserving their freedom of manoeuvre, or ‘agency’ to use the more awkward but currently fashionable word. Southeast Asia was a hot zone for most of the cold war, as devastating wars raged across Indochina, while smaller-scale insurgencies and political violence took a horrific toll elsewhere. ASEAN came into existence, in 1967, with the aim of projecting greater political cohesion across such a fractious region. It was one of the first international organisations formed by Southeast Asians without external prompting, a point that still has political resonance.

None of the five founding ASEAN members was officially neutral, however, in the mould of Sweden or Switzerland (the latter only joined the UN in 2002). All, in fact, were avowedly anti-communist, including Indonesia’s military-dominated government after 1965. In this important sense, ASEAN’s founders were aligning with each other from the beginning. After the communist victories of 1975, Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia were not neutral in any meaningful sense either, partly because their respective patrons awkwardly straddled the Sino-Soviet split. Burma’s socialist junta probably came closest to neutrality in Southeast Asia, though it was eventually persuaded out of its self-imposed seclusion to join ASEAN in 1997, around the same time as the three Indochinese countries.

For contemporary Southeast Asia and its expanded ASEAN membership, the distinction between non-alignment and neutrality is more than a matter of historical or semantic significance, as geopolitical divisions are again on the rise. Yet this nuance sometimes appears lost among ASEAN’s political leaders and policy elites, who increasingly frame their foreign policy in terms of neutrality. A desire for neutral status is most often espoused in connection with fears about escalating China-US rivalry and the perceived risk that Southeast Asia will again become geopolitically riven. Under President Ferdinand Marcos II, the Philippines has become the outlier within ASEAN, emphatically doubling down on its alliance with the US to protect it against China’s maritime expansionism. Manila has no problem with counter-balancing alignments either.

Neutrality means consciously avoiding partiality in conflicts and disputes among third parties. Malaysia’s Prime Minister, Anwar Ibrahim, has used the word repeatedly since assuming office, which has not gone unnoticed in China’s Global Times. This is in spite of Anwar being more effusive than his predecessors or most of his ASEAN counterparts in condemning Russia for invading Ukraine. Neutrality is at odds with Malaysia’s membership of the Five Power Defence Arrangements, whereby Australia, New Zealand and the UK have a quasi-treaty commitment to come to Malaysia and Singapore’s aid in case of external aggression. Australia maintains a low-profile military presence on the Peninsula for that purpose. Malaysia benefits through access to shared surveillance and intelligence. Malaysia also conducts regular military exercises with the United States. Neutrality is further at odds with ASEAN’s softer, collective commitment to support its own members against external threats, for example through the South China Sea Code of Conduct, which involves all 10 members. Yes, the Bandung Principles enshrines ‘abstention from intervention or interference into the internal affairs of another country’. But again, non-interference is not the same thing as neutrality.

Indonesia’s Foreign Minister Retno Marsudi has explicitly distanced herself from the term, claiming that ‘our independent and active foreign policy does not mean neutrality and disengagement’. But some foreign policy commentators in Indonesia have articulated a desire for strategic equidistance from the US and China in terms of neutrality. If taken up by the President-presumpt, Prabowo Subianto, the term is likely to become more entrenched across ASEAN.

Neutrality has a tangible and legal definition in wartime. In case an armed conflict breaks out between the US and China, for Indonesia and the Philippines, the concern is that vessels and aircraft belonging to the belligerents will transit through their archipelagic waters. This is also a hot-button issue in Australia-Indonesia relations, and not simply in relation to AUKUS.

Yet neutrality does not feature significantly in the foreign policy traditions of most Southeast Asian countries. Nor is it in their best interests.

Loose non-alignment is a more prudent and flexible posture to aspire towards. The leading exponent of this within ASEAN is Singapore, which sees no contradiction between its adherence to non-alignment and pursuit of close defence relations with the United States and Australia, or close economic and diplomatic relations with China. Singapore’s diplomacy, in truth closer to ‘poly-alignment’, ultimately rests on the ability to credibly defend itself. Singapore consciously frames its key foreign policy decisions as positions of principle, rather than allegiance to another country. That is perhaps the most persuasive definition of non-alignment in contemporary terms. Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong pointedly offered a detailed endorsement of Australia’s regional security role at his joint press conference with Prime Minister Anthony Albanese this week, repeating Singapore’s offer to host visits by Australia’s nuclear-powered submarines in future.

Vietnam’s omni-directional foreign policy shares some basic similarities with Singapore, though Hanoi has adopted a stricter policy regarding not hosting foreign military forces, or forming alliances, than most other ASEAN members.

Neutrality without the independent means to defend oneself is the worst of all strategic settings for ASEAN countries. China wants Southeast Asian countries to cut their security ties to the US and its allies. It has been applying collective pressure on ASEAN, through the South China Sea Code of Conduct negotiations, to give it a veto over exercises with navies and air forces from non-littoral states. If the South China Sea becomes a bastion for the PLA to dominate uncontested, neutrality will feel more like subjugation for the maritime states of Southeast Asia, including Vietnam.

A posture of non-alignment offers a more optimal standpoint than neutrality for ASEAN member states to exert their agency in foreign policy. This includes broad-based cooperation with a dialogue partner like Australia, extending into defence and security. The expectations on either side need not be exclusive, or bloc-based, but can be more portfolio in nature. Just ask Singapore.