In Peter Layton’s recent post Australia’s many ‘maritime strategies’ he noted that:

In Peter Layton’s recent post Australia’s many ‘maritime strategies’ he noted that:

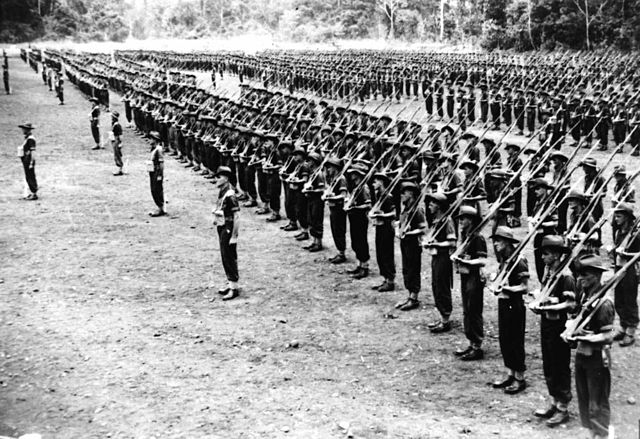

[A] maritime strategy of land force expeditionary warfare across the Indonesian archipelago… sounds somewhat reminiscent of the last days of WWII, when Australia undertook amphibious operations against by-passed Japanese forces while the US drove onto Tokyo Bay and victory. It’s not obvious how valuable that strategy is; Peter Charlton labelled it an unnecessary war.

This period of Australian strategic history holds important lessons for understanding Australia’s role in the region and some insights into what can happen to junior partners of a coalition when national interests diverge.

The tag ‘unnecessary war’ has become a catchcry for Australia’s operations in 1944–45. It remains a well-used phrase but has been largely discredited. Charlton’s version of events clouds the reality of Australian strategic objectives at this time.

Several key issues shaped Australian strategic decision-making in 1944–45. At the end of 1943, for the first time in either WWI or WWII, Australia’s military forces were not fighting at the forefront of Allied operations that were leading directly to the defeat of the main enemy. Instead, from late 1943 (and for all subsequent conflicts) Australia needed to determine its military strategy on the basis of the pursuit of its particular national strategic interests.

The Australian Government faced some serious issues at the end of 1943: grave manpower problems, coalition warfare where the interests of the US theatre strategic commander General Douglas MacArthur no longer accorded with Australian national interests, Australia’s role within the Allied coalition, the role of the Australian military in Allied operations to defeat Japan (including participation in the invasion of the Japanese mainland), Australia’s obligations to its mandated territories in the South Pacific, Australia’s role as a regional security actor and where Australian interests would lie in a post-war Asian security environment.

To write off such decisions and actions as leading to an ‘unnecessary war’, is to deride the key strategic interests that the Australian Government identified in 1944–45 and the complexity of the coalition environment. Charlton’s position has been thoroughly revised by a number of military historians over the past two decades, most notably by David Horner’s masterful study High command: Australia’s struggle for an independent war strategy, 1939–1945. Horner’s study is widely regarded as the strategy volume that the official history Australia in the war of 1939–45 never produced. I investigated these issues comprehensively in my biography, The architect of victory, of Lieutenant General Sir Frank Berryman, Australia’s chief of operations in the Pacific War, as did Dr Karl James of the Australian War Memorial in his recent work The hard slog: Australians in the Bougainville campaign, 1944–45.

Three clear issues that the Australian Government faced and the solutions to them emerge from those texts. Firstly, the majority of these ‘bypassed’ areas were either Australian territory or mandated territory. The government and the Commander-in-Chief General Sir Thomas Blamey were not willing to let these territories remain under Japanese control for an indefinite period, just as the government would not have allowed any part of the Northern Territory or Queensland to have remained under Japanese control if it had been occupied. Blamey believed that the local populations of New Guinea, New Britain and Bougainville should not be treated differently on the basis of the colour of their skin. The US made the same decision in regards to the Philippines.

Secondly, the nation faced a major manpower shortage. By 1944, with the threat to the nation passed, the size of the military was unsustainable. The economy was making a significant contribution to the Allied war effort, in particular to supplying MacArthur’s US forces in the region, and therefore either the large numbers of Australian troops in the South Pacific had to be released to the war economy or the government had to reduce the size of the Australian expeditionary force fighting further north with MacArthur.

The government concluded that to maintain its rightful place in the Allied coalition and to achieve Australia’s aim of maintaining its ‘status at the peace table’ troops had to be made available to participate in the operations around the Philippines and Borneo and later for the invasion of Japan in 1946. It must not be forgotten that that neither the Prime Minister nor Blamey was privy to the development of the atomic bomb. It was understood that the war would last until 1946 or 1947.

MacArthur had set a minimum contribution of a corps of two to three divisions for the invasion of Japan. In order to achieve this objective and to release manpower to the economy it was critical that key Japanese positions in Bougainville and New Guinea be eliminated in a timely and effective manner. These operations were sanction by the government and MacArthur’s HQ in accord with Australian strategic priorities.

The final issue was the use (or misuse) of the Australian 1 Corps in Borneo by MacArthur. MacArthur had decided, for political reasons, that this formation would not be used in the climactic battles of the Philippines but rather in the liberation of Borneo. Blamey raised concerns with both MacArthur and the Australian Government about the lack of a strategic rationale for these operations. Here MacArthur played a duplicitous hand, telling the Prime Minister, John Curtin, that the US Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) demanded the operations go ahead and that to cancel ‘would have grave repercussion for the Australian government and people.’ At the same time he told the JCS that the Australian Government demanded that, for political reasons, they go ahead. The government found itself in a position where it believed it could not say no to MacArthur and its major coalition partner, even if the rationale for those operations remained weak.

It is only by ignoring the Curtin government’s strategic objectives, the application of hindsight, and an assumption that the government knew of the atomic bomb, that this ‘war and strategy looks ‘unnecessary’’.

Peter Dean is a fellow at the Strategic and Defence Studies Centre at the ANU and the editor of Australian 1942: In the Shadow of War (2012) and the forthcoming Australia 1943: The liberation of New Guinea (October 2013). Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.