This post is an edited excerpt from ASPI’s Counterterrorism yearbook 2021, released today. A full PDF of the yearbook, which includes notes and sources for each chapter, is available for free download from ASPI’s website.

Online memes have been a tool for recruitment and propaganda for established extremist movements for many years. Whether the memes are created spontaneously by grassroots sympathisers or are part of coordinated and deliberate strategies laid out by the leadership of extremist groups, they reflect and transmit the movement’s ideology. Overt or coded references serve as a wink to insiders and, their creators may hope, an intriguing hint that will make outsiders want to know more.

However, what’s occurred over the past several years, and accelerated dramatically since the beginning of the global Covid-19 crisis, is the opposite process. Beyond just extremist movements generating memes, memes are now also inspiring extremist violence.

It’s too early to fully understand how the dynamics of these digital-native forms of extremism may differ from more traditional extremism, which begins offline and later moves into online spaces. This analysis will be further complicated by issues involving the recording of digital history, particularly where crucial historical evidence is in fringe or ephemeral social media spaces that may be deleted before it can be archived or analysed.

The clearest example of this so far is the Boogaloo, a US-based phenomenon that’s been linked to several violent attacks in 2020. At least two people have been charged with terrorism offences, multiple murders of law enforcement officers, and an alleged plot to kidnap Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer.

These forms of extremism are born and nurtured in online spaces. The ambiguity of memes and of meme culture plays a crucial role, but other factors unique to digital platforms are also important, such as the potentially radicalising role of algorithms and the ways in which social media platforms that prioritise engagement create inherently escalatory social dynamics. The media spotlight has also been a major galvanising factor.

Understanding the ways in which these digital-native extremisms differ from traditional or even digitised extremist movements (that is, extremist groups that began with a well-established offline existence and later moved into being active in online spaces) will be important in order to respond to them effectively.

The phenomenon now known as the Boogaloo can be traced back at least as far as 2018, through references to the ‘Civil War 2: Electric Boogaloo’ on the social media platforms Facebook and Reddit. This was an adaptation of an existing meme that used ‘Electric Boogaloo’ (a reference to the Breakin’ 2: Electric Boogaloo movie) as a reference to a poor quality sequel. The ‘Civil War 2: Electric Boogaloo’ meme was originally used by US-based gun rights activists to refer to the consequences of government or law enforcement passing stricter gun control laws or trying to ‘take their guns’.

The meme bubbled along over the course of 2019, spreading across multiple social media platforms. It cross-propagated with other memes and cultural narratives and received a particular boost on anonymous imageboard 4chan, especially from its /k/ board, which is dedicated to discussing weapons. 4chan and other chan boards, including 8chan and now 8kun, are infamous for having incubated toxic, misogynist, racist, anti-Semitic and at times overtly white supremacist cultures. Across 2019, the /pol/ boards (dedicated to discussing politics) on both 4chan and 8chan were linked to multiple mass shootings, including the Christchurch shooting.

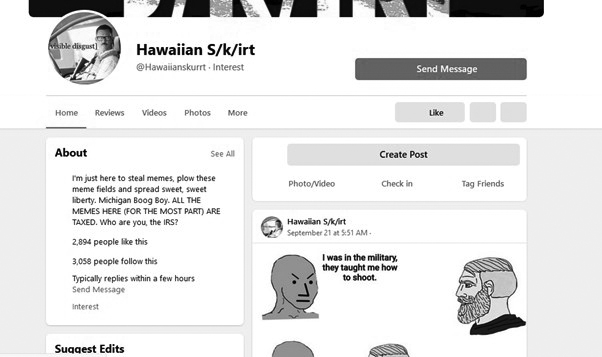

Meanwhile, on the /k/ board the Boogaloo meme was picking up steam. The legacy of this /k/ board connection can be seen even on different platforms, for example in the names of Facebook groups. In the example in Figure 1, run by a self-professed ‘Michigan Boog Boy’, the visual style and references of the Boogaloo, including the infamous Hawaiian shirt, sit alongside /k/ board and other chan culture references.

Figure 1: Facebook page, captured 29 September 2020

Leading up to early 2020, some of the visually distinctive elements of the Boogaloo began to emerge. Many were jokey references to codewords, which social media users adopted to avoid content moderation. The Hawaiian shirts, for example, started as a nod to the ‘big luau’, which some users began using in place of ‘Boogaloo’ in an effort to avoid detection. The igloo was also adopted as a symbol after the ‘big igloo’ became another Boogaloo codeword.

At this stage, there was nothing that could reasonably be considered a Boogaloo ideology. Conceptually, the Boogaloo consisted of vague references to desiring civil unrest, opposition to law enforcement (and tax agencies) and a heavy emphasis on gun rights, but beyond those broad attitudes there was no coherent ideological basis common to all or even most people engaging with the meme. There was no widely held consensus on what should spark the civil war, or what should happen after it. There was also no centrally organised group structure or clear dividing line between who was or was not a ‘Boogaloo Boi’. For many, it was more a long-running social media joke than a meaningful belief or desire for real violence.

Over the course of 2020, however, that began to change rapidly. This was partly a result of external events and how the social dynamics of social media platforms drive responses to those events. The social dynamics of platforms such as Facebook and Reddit create cycles of escalation, in that the design of the platform encourages users to compete to generate engagement, and the most engaging content is often the most extreme. It’s also the most likely to be algorithmically recommended or surfaced to others.

However, by far the greatest factor in driving the evolution of the Boogaloo from a series of loosely linked social media groups into something much closer to an extremist movement seems to have been the media spotlight.

As the tumult of 2020 began to unfold, Boogaloo Bois, in their Hawaiian shirts and often heavily armed, became a highly visible presence in protests across the US. They were active in gun rights rallies in January, anti-lockdown protests in May and George Floyd protests in June.

Three men in Nevada, who were described in court documents as self-identified members of the Boogaloo and belonged to a Nevada-based Boogaloo Facebook group, were charged with terrorism offences in connection with plans to use the protests as a pretext for escalating violence and targeting law enforcement. In another dramatic incident, an air force sergeant allegedly inspired by the Boogaloo ambushed and killed a California sheriff’s deputy, shot to death a federal security officer outside a courthouse and critically injured another, and stole a car and wrote Boogaloo-related phrases across it in his own blood before finally being caught. Over the course of one week in October, a string of at least 16 arrests took place, most connected to a plot to kidnap Michigan’s Governor, Gretchin Whitmer, potentially murder her and spark a civil war. A senior law enforcement official reportedly told NBC News that the group ‘believes’ in the Boogaloo. The group’s leader, Brandon Caserta, had also posted videos to TikTok of himself in a Hawaiian shirt as he went on an anti-government tirade.

There’s a reasonable debate to be had over how pivotal the Boogaloo was in inspiring those incidents and whether, if the Boogaloo hadn’t existed, these individuals would simply have gone on to commit violence in the name of some other cause. The same questions could be posed about almost any form of extremism, however. The fact that law enforcement consider the movement significant enough to mention it in court filings—and that one perpetrator considered it significant enough to write in his own blood— suggests that the Boogaloo is important to consider as a form of extremism in its own right as well as in combination with other forms of anti-government extremism.

All of those incidents were accompanied by waves of mainstream media attention, which sought to define and characterise the Boogaloo for their audiences. The Boogaloo was described variously as a ‘group’, a ‘movement’, a ‘far-right militia’, ‘white nationalists’ or even ‘white supremacists’.

This coverage was, of course, voraciously consumed by the Boogaloo Bois themselves. The subsequent debates and arguments over whether the media’s characterisation of the Boogaloo was accurate (for example, between those who objected to being characterised as white nationalists and those who were happy to own the label) exposed contradictions that had previously been papered over.

In short, the ambiguity of memes and meme culture had, for a time, allowed the Boogaloo to mean almost anything to almost anyone, so long as violence against the state was involved. Libertarians and anarchists saw an uprising of the people against the oppressions of government; white nationalists saw an uprising of white people against political correctness and the perceived oppression of whites in a multiracial state. They both hung out in the same Facebook groups and shared the same Pepe, Shiba Inu and Hawaiian shirt memes, largely unaware that those memes were being interpreted differently by each of them.

Under the harsh glare of the media spotlight, however, those internal fractures were exposed. It was the media’s efforts to define the Boogaloo that pushed them to begin to define themselves.

The media coverage complicated this in another way, too. As is so often the case, the visibility that the media gave sent a wave of new people flooding into the Boogaloo groups across social media, and particularly on Facebook. These new users thought they were joining the kinds of groups that the media had told them to expect: far-right and with at least a lean towards white nationalism. This meant that, just at the time the Boogaloo groups were seeking to define themselves, they also faced an influx of people looking to join far-right and white-nationalist groups, thereby adding support to those elements of the existing Boogaloo community.

The closest thing the Boogaloo had to leaders at the time were the administrators and moderators of the largest Boogaloo Facebook groups, some of which had tens of thousands of members. Some of those individuals used their platform to reject the idea that the Boogaloo was a racist movement, expressing support for Black Lives Matter protesters and asserting that the Boogaloo was about opposition to law enforcement and the state, not about racial hierarchies.

That overt rejection of racism wasn’t uniform, however, and there continues to be a significant racist element running through the memes and conversations in Boogaloo communities. For example, there was a brief period on some Boogaloo Reddit boards in which Boogaloo Bois of colour were posting pictures of themselves to prove that Boogaloo followers were neither all white nor white supremacists. Some of those posts garnered hundreds of positive comments and upvotes. On the same Reddit boards, however, thinly coded references to shooting black people are casually dropped in with no disapprobation from other posters.

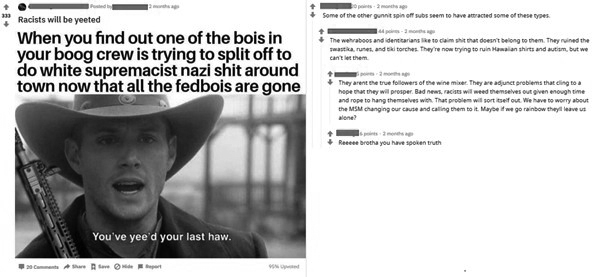

What this has led to is an argument over who the ‘true’ Boogaloo Bois are, who has the right to use their symbols and who has the power to decide what they stand for. In the screenshot in Figure 2, for example, moderators of a Reddit board took a stance opposing racism (while implicitly acknowledging that ‘white supremacist nazi shit’ is a problem within Boogaloo groups). As commenters on the post noted, however, other explicitly white supremacist communities on Reddit are also using the Boogaloo symbols. Commenters suggest those groups are ‘not the true followers’ of the Boogaloo.

Figure 2: Discussion on a Boogaloo Reddit board

To be sure, internal disagreements over what the movement stands for and where power lies are nothing new for extremist groups. The Boogaloo and other similar digital-first forms of extremism aren’t completely different or separate from other forms of extremism and are likely to demonstrate many of the same dynamics and characteristics.

What does appear to be different, however, is the speed of escalation (with barely a year from a series of mostly joking memes to all-too-real murders and alleged terror plots), accompanied by lingering confusion and decentralisation. The lightning pace of radicalisation has far outstripped the process of ideological growth; in short, despite multiple committed and planned attacks, it’s still not clear who the Boogaloo Bois are or what they stand for, other than violence for violence’s sake.

That hollowness at the heart of the Boogaloo doesn’t make it less dangerous. If anything, it makes it more volatile. For the majority, it’s still mostly a funny internet joke; for a handful, it’s something to kill and die for. This memetic ambiguity is likely to be easily hijacked to serve a range of agendas, or to feed into the world views of self-radicalising individuals who can read into it almost anything they want.

Depending on how you want to count, the Boogaloo as something closer to a meaningful movement than a meme is barely a year and perhaps even only a few months old. It’s far too early to say what its ultimate impact will be. What it has already proved, however, is the way in which, given the right digital environment and the right external circumstances, something as ambiguous as a series of memes and jokes can rapidly transform into the kind of radicalising force that drives some individuals to ambush law enforcement, commit murder, write in their own blood across a stolen car or plot to kidnap a politician. Whatever the Boogaloo may evolve into, one thing’s clear: it’s not just a joke anymore.