The quest for independence signals a nation’s pursuit of sovereignty and control over its internal and external affairs. Sovereignty serves as the cornerstone upon which a country’s identity, governance, security, and international relationships are built. In the vast expanse of the Indo-Pacific, this quest for self-governance intertwines with Australia’s strategic goals of regional stability, diplomatic bonds, and economic cooperation.

Strong governance bolsters regional stability, fosters diplomatic relationships, and enhances economic cooperation. Safeguarding the independence of island neighbours is imperative for Australia’s own geopolitical resilience and stability.

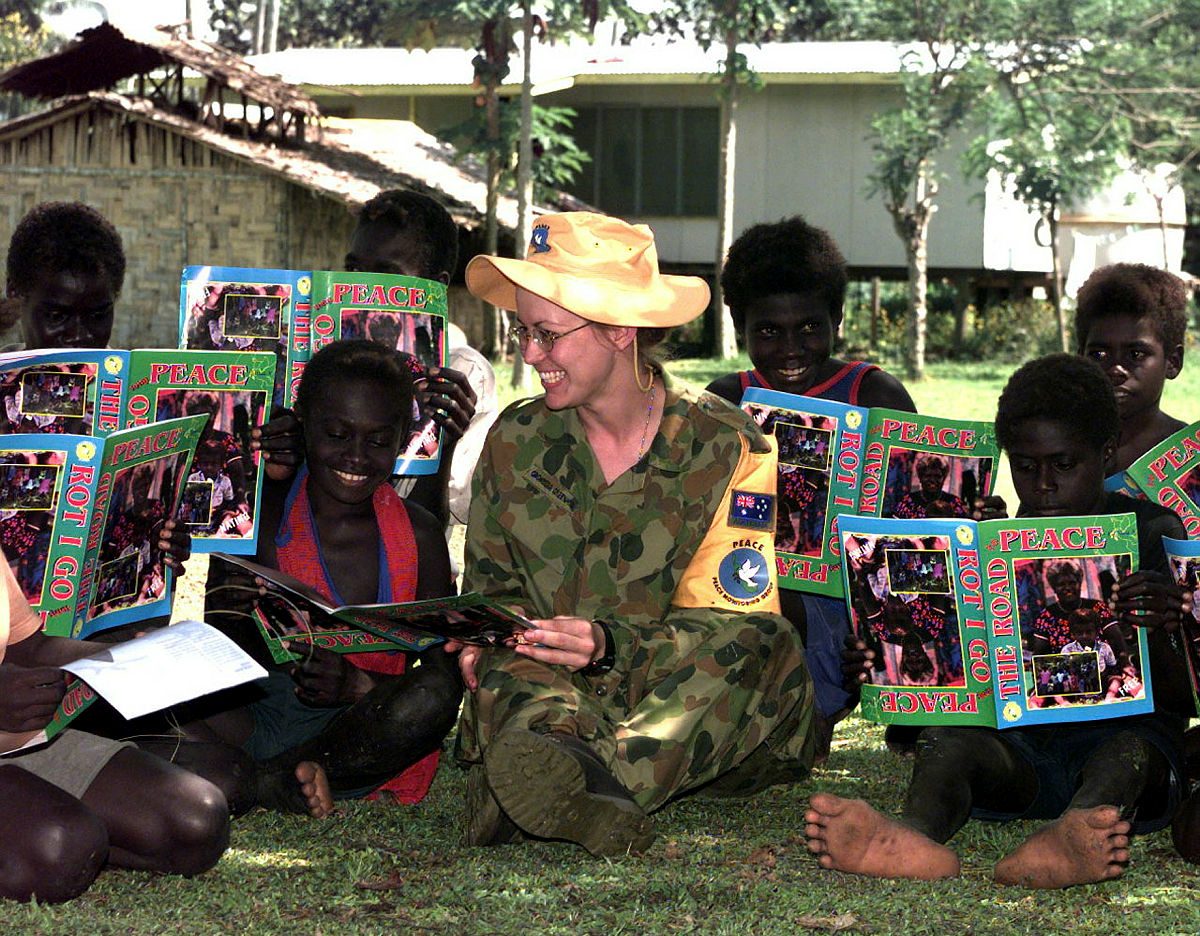

For over 75-years, Australia has supported peace operations, both in United Nations deployments and as a leader in regional missions. Australian-led regional peacekeeping missions were at their peak from the late 1990’s to the mid 2000’s, notably in Bougainville, Timor Leste and Solomon Islands.

The pursuit of sovereignty underpinned struggles in Bougainville and East Timor and Australia’s monitoring of elections, truces, and ceasefires helped prevent further major violence and bring stability.

Bougainville’s struggle traces back to the late 19th century and subsequently involved German, British, Japanese, Australian, and Papua New Guinean rule. A decade-long civil war from 1988 with an estimated death toll of 15,000, the displacement of 70,000 people, and the widespread destruction of infrastructure was one of the most severe in the region since World War II. At the request of the PNG government, Australia initially supported it’s blockade using helicopters and patrol boats. Australia later played a crucial role in restoring peace by forming Operation Bel-Isi to oversee the 1998 ceasefire between the Bougainville Revolutionary Army (BRA) and the PNG Government. Through the truce monitoring group and the subsequent peace monitoring group, around 2,100 Australian military, police, and civilians, and defence force personnel from New Zealand, Fiji, and Vanuatu, were deployed to the island until their withdrawal in 2003.

Meanwhile, Timor Leste began its pursuit of sovereignty in 1975 through its declaration of independence from Portugal. This attempt was thwarted by the invasion and occupation by Indonesian forces, and Timor Leste was integrated into Indonesia in 1976.

There followed an unsuccessful pacification campaign spanning two decades during which an estimated 100,000 to 250,000 people died. A UN-supervised referendum was held in 1999 and an overwhelming majority of East Timorese voted for independence from Indonesia. In the weeks that followed, Indonesian-backed anti-independence militias initiated a large-scale retaliatory campaign, resulting in around 1,400 deaths and the displacement of nearly 500,000 Timorese people, as well as the destruction of infrastructure. From 1999 to 2012 Australian peacekeepers were deployed in both regionally led and UN peacekeeping and humanitarian assistance operations. In 2002, Timor Leste was internationally recognised as an independent state.

These examples showcase Australian statecraft at its best, working with regional neighbours to restore peace during a conflict driven by a quest for stability, independence, and sovereignty.

There are many similarities between Bougainville and Timor Leste. They are both small tropical island communities close to Australia, one in Southeast Asia and one in the South Pacific, and both voted overwhelmingly for independence in internationally-sanctioned referendums. In Timor Leste, 78% voted for independence which was achieved within three years. In Bougainville, 97.7% voted for independence and yet four years later the referendum results are subject to ratification by PNG’s parliament.

There’s been speculation that PNG is unlikely to ratify the independence vote, fearing this could set a precedent encouraging other provinces to break away including outlying islands and resource-rich highland regions that are already difficult to govern from the capital. That could see Bougainville unilaterally declare independence, risking more unrest.

For Canberra, either situation will present significant challenges for regional statecraft with both PNG and Bougainville situated within Australia’s inner security arc. For 20-years, Australia has delicately balanced relations between PNG and Bougainville. Tensions flared in late 2022 when, during a visit to PNG by Deputy Prime Minister and Defence Minister Richard Marles, an announcement of support for the PNG Government saw a backlash from Bougainville’s President.

The strategic significance of PNG and Bougainville for Australia’s security cannot be overstated. PNG is a key security ally and a significant economic partner. That significance is elevated by PNG’s proximity to Guam, to critical undersea cables connecting military facilities in Hawaii and Australia, and to its position on sea lanes connecting Australia to the US that are key to trade and security.

Bougainville is close to the Solomon Islands, where China seeks increased influence.

Any conflict or unilateral declaration of independence in Bougainville would hold profound implications for Australia’s security dynamics in the Indo-Pacific. Should PNG vote against Bougainville’s referendum results, and if that leads to a unilateral declaration of independence and civil unrest, what will be Australia’s response?

Twenty years ago, Australia’s defence policy was focused on maintaining regional stability and partnerships through contributions to regional peacekeeping operations and to global counter-terrorism operations in Afghanistan and Iraq. Today, both the world and our region have undergone a dramatic shift spurred on by major power competition. Australia has also significantly fewer ADF personnel on peacekeeping missions.

As the geopolitical landscape changes, Australia’s recent defence strategic review underscored the Indo-Pacific’s evolving dynamics and the growing influence of China. Preserving peace and nurturing strong relationships with both PNG and Bougainville align with Australia’s strategic objectives. But the prospect of needing to again deploy peacekeepers during a conflict raises complex challenges for necessitating a delicate balancing act to safeguard crucial relationships.

The unfolding situation in Bougainville could again test Australia’s ability to navigate complex geopolitical landscapes.