The confluence of forces built around shared unease and growing anxiety over the implications of China’s rapid military expansion, salami-slicing territorial creep and ‘wolf warrior’ diplomacy is fertile ground for the revival of the quadrilateral security dialogue (Quad) between Australia, India, Japan and the US. The four democracies share the strategic assessment of China as a disruptive force in the Indo-Pacific.

Quad 1.0 was interred in 2008 when Prime Minister Kevin Rudd, bowing to China’s sensitivities, pulled Australia out. The concept went on hold with Shinzo Abe’s loss of office in Japan, the advent of the Obama administration in the US, and the anti-American bent of Manmohan Singh’s communist party and other left-leaning allies in India.

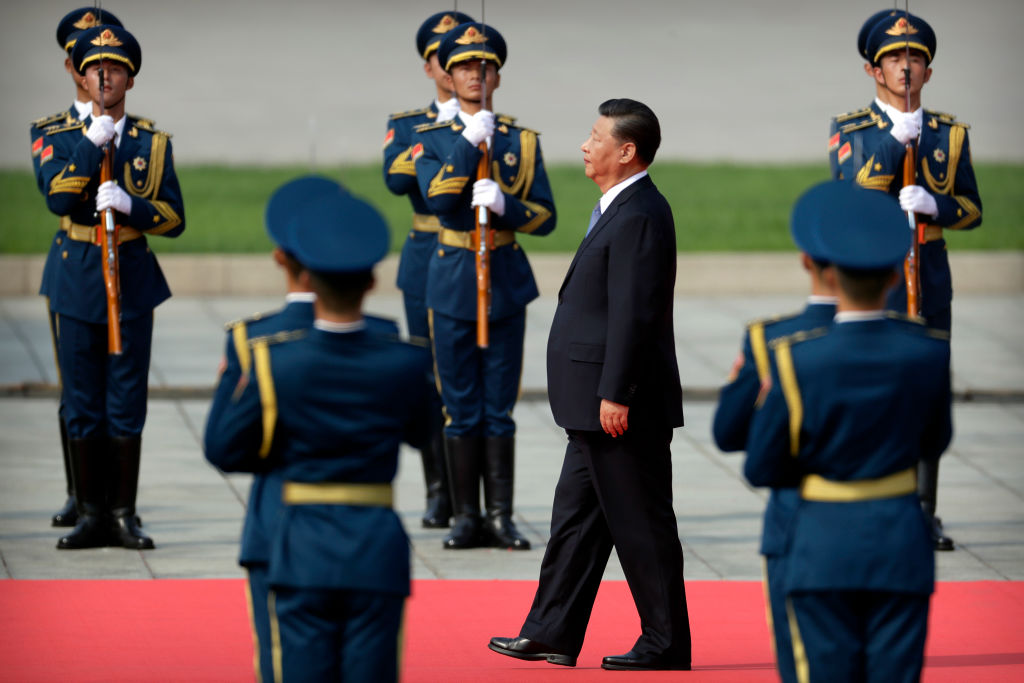

As part of a fundamental reorientation of India’s foreign policy, PM Narendra Modi began aggressively pursuing diplomatic initiatives to the east, including investing in personalised diplomacy with China’s President Xi Jinping as well as with Abe. Australia’s unease has been rising over aspects of China’s behaviour in the region and interference in Australian politics and public life. The Trump administration has identified China as the top US security threat. And Japan is trying desperately to adjust to the shape of Asia’s new cold war.

China’s re-emergence as a comprehensive national power raises multiple points of concern that provide the backdrop to the fresh interest in Quad 2.0. China has morphed from its historical identity as a continental power into a modern maritime power with growing power-projection capability across the Indo-Pacific. It has followed a string-of-pearls strategy in the Indian Ocean, backed by a growing naval capability, to choke India around its littoral and to check it on land by courting Nepal and its all-weather friend Pakistan. It has engaged in assertive behaviour in the East and South China seas to build sprawling, interlinked militarised facilities on remote and uninhabited islands—many of them disputed on ownership—to challenge US strategic primacy.

Shashi Tharoor, former chair of India’s Parliamentary Standing Committee on External Affairs, rightly notes that the 15 June military clash with China in the Galwan Valley in Ladakh presents India with the stark choice of capitulating to China’s military blackmail or embracing the US free of the historical burden of anti-Americanism. Gautam Bambawale, the recently retired Indian ambassador to China, thinks the clash will mark the date on which China finally ‘lost India’ strategically.

Australia’s former ambassador to China Geoff Raby notes: ‘[A] series of important announcements … have made it clear that the Australian government now regards China as a strategic competitor and a revisionist power that must be resisted.’ China’s retaliatory measures against Australia include impediments on beef, barley, students and tourists, as well as aggressive statements from Chinese diplomats.

On 30 June, after China enacted a sweeping new national security law for Hong Kong, Japan’s Chief Cabinet Secretary Yoshihide Suga called the move ikan (regrettable), which is just one step short of the most critical word in the Japanese diplomatic lexicon, hinan (denounce). As the situation in Hong Kong gradually deteriorated, Japanese officials had used incrementally stronger words—from chūshi (closely monitoring) to yūryo (seriously concerned).

The 10-member Association of Southeast Asian Nations issued an unusually tough statement on China on 27 June reaffirming the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea as the proper basis of sovereign rights and entitlements in the disputed South China Sea.

On 13 July, following the dispatch of two aircraft carriers to take part in one of the largest naval exercises in recent years in the South China Sea, US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo called out China’s behaviour as illegal in a rare direct challenge to Beijing. ‘The world will not allow Beijing to treat the South China Sea as its maritime empire’, he said. Full-spectrum China–US strategic jostling will peel away the layers of safety nets against deliberate or inadvertent military conflict.

Australia, Japan and the US were drawn to the ‘Indo-Pacific’ conceptual frame as a convenient analytical tool to incorporate India into their strategic calculus. It integrates geography, the ‘free and open’ principle and democratic values into one strategic construct.

However, the level and quality of economic interaction of the four Quad partners with China vary enormously, as do their territorial disputes and their fears of entanglement in others’ quarrels. There can be no expectation of automatic military assistance in any armed conflict with China arising from the territorial disputes between Japan and China and between India and China. The volatility and erratic decision-making style of the Trump administration and its transactional approach to foreign policy raise doubts about the reliability of its security guarantee. All this explains the wariness towards the Quad by the partners. That is likely to subside in the rapidly changing geopolitical landscape.

The origins of the Quad are entirely benign. After the Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami on Boxing Day 2004, the four navies closely coordinated disaster relief operations and gradually consolidated habits of cooperation in the vast maritime space of the Indo-Pacific. Even today there is no appetite among any of the four for an upgrade of the Quad from a web of intersecting bilateral-cum-trilateral relationships resting on shared strategic worldviews and promoting habits of cooperation to a hard-edged anti-China security alliance.

However, caught between an increasingly assertive and bellicose China and a US that grows more unpredictable and less reliable by the month, Australia, India and Japan are having to ‘thread the needle’ of a fraught future for the Indo-Pacific amid the collapsing pillars of the liberal international order. Nevertheless, while the stated message is an informal security dialogue, the message as received in Beijing is that the Quad is a coalition to contain China.

To understand why, China’s leaders might want to hold their statements and actions to the mirror.