The conflicts—some might be better described as spats—between China and a number of European countries might provide as many clues about China’s aspirations and behaviour as anything said in California between Barack Obama and Xi Jinping.

The sharpest issue of the moment is a trade dispute over the European Union’s intention to slap heavy duties on solar panels from China on the ground that they’re suspected of being heavily subsidised and sold below their true cost, being dumped on the European market. The EU has given China a couple of months’ reprieve to disprove the dumping allegation but if it fails to satisfy the EU within that time, then the duties will rise to an average of 47.6% from the present rate of nearly 12%.

China has responded in two main ways. It will investigate whether wines from France, Spain and Italy are being subsidised. Wine exports from those countries have been increasing and any restriction would hurt the wine growers markedly. The second response has been by a sharp verbal attack on the EU in the People’s Daily usually regarded as reflecting the Chinese Government’s views with some precision. The newspaper told the EU that its failure to recognise that its power was declining risked further retaliation from Beijing. ‘The change of the times and the shifts of power have failed to change the condescending attitude of some Europeans’, the editorial said.

China had campaigned hard to prevent the EU from imposing the increased tariffs. In many ways that isn’t surprising. Most countries threatened with a high tariff by an importer would try to prevent its passage into law. A threat of retaliation also often occurs in trade disputes. The twist lies in China’s method. Not all European countries supported the rise in the tariff, though France, Spain and Italy do. Brussels is pushing ahead with the proposed tariff hike despite the internal dissension. Wine, important as it is for particular regions in which it is grown, is a minor item in the EU’s exports to China.

The People’s Daily said that China had plenty more cards to play. China is showing signs of being somewhat fed up with the EU’s often ponderous decision-making processes and being more inclined to deal with individual countries, especially Germany, which it regards as being the leader of the EU. Germany opposed the imposition of the high tariffs against the solar panels.

One question the row raises is whether China will seek to exploit the splits within the EU and by dealing with individual countries seek to influence them one by one—a method China is seen as using within Asia. A wider question is whether, in seeking to be the equal of the United States, China will reduce the importance of other countries to China. Putting the EU in its place would be a start.

The trade dispute apart, China has two other major rows with European countries. David Cameron, the Prime Minister of Britain, recently received the Dalai Lama, for which China has demanded an apology. Britain is strongly disinclined to offer one. The dispute has cast uncertainty over Mr Cameron’s proposed visit to China this year. The other European (though not EU) country which is out of favour with China is Norway. This row dates back to 2010, when the Nobel committee in Norway awarded a Chinese dissident, Liu Xiaobo, the Nobel Peace Prize. Liu Xiaobo was then (and remains) in prison in China.

Under the terms of Alfred Nobel’s will Norway was designated as the country in which the peace prize should be decided. The Norwegian Government has protested in vain that it had nothing to do with the choice of Liu Xiaobo but China appears to hold it responsible all the same, not bothering about the distinction between an independent body within Norway and the Norwegian Government.

China has recently gained observer status with the Arctic Council, a group of countries bordering the Arctic. Observers don’t have the right to speak or vote at Arctic Council meetings but may attend. China will thus be in a good position to keep an eye on developments in the Arctic with all their resource, environmental and shipping implications. This seems in keeping with China’s aspirations to be a great power. The EU has not yet achieved observer status within the Arctic Council.

Iceland was a strong supporter of China gaining observer status. China and Iceland are negotiating for a free trade agreement, which would be the first between a European country and China (New Zealand has a free trade agreement with China, having recognised China as a market economy.) The EU has thus far refused to recognise China as a market economy—a precondition China sets.

None of this scattering of clues amounts to a precise redefining of China’s attitudes or a certain guide to its future actions. Yet some shapes appear to be emerging.

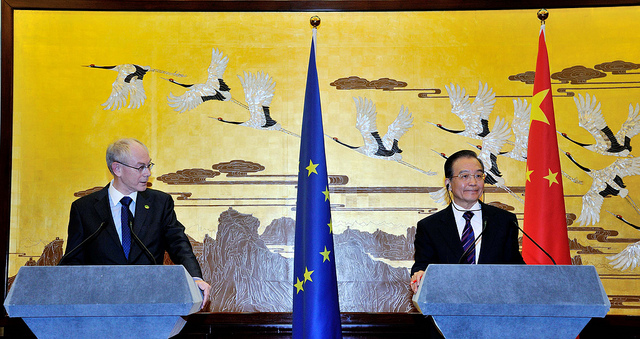

Stuart McMillan is an adjunct senior fellow in the School of Social and Political Sciences at the University of Canterbury. He is also a research fellow in the National Centre for Research on Europe at that university. Image courtesy of Flickr user President of the European Council.