Originally published Jan 14, 2013.

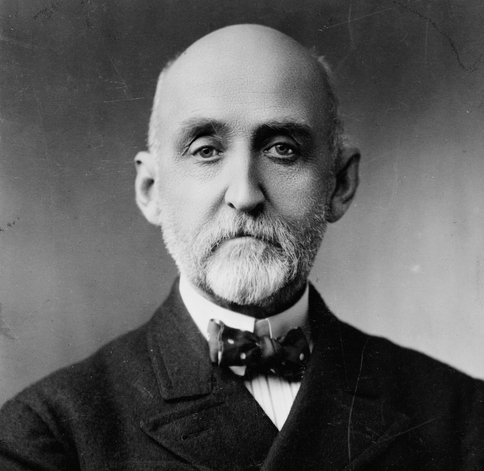

One of the things I like most about the summer break is the opportunity to catch up on some reading. This time around one of the items on my reading list was a revisit of a 1911 essay ‘The Panama canal and sea power in the Pacific‘ by the great sea American power theorist Rear Admiral A. T. Mahan.

One of the things I like most about the summer break is the opportunity to catch up on some reading. This time around one of the items on my reading list was a revisit of a 1911 essay ‘The Panama canal and sea power in the Pacific‘ by the great sea American power theorist Rear Admiral A. T. Mahan.

The reason I wanted to read this particular piece again was because there’s a turn of phrase in there that has stuck with me and which seems pertinent to our deliberations about the future security structure of the Asia–Pacific region. Mahan, as was often the case, was ahead of the pack in thinking through the strategic implications of the opening of the Panama Canal—still three years away at the time of the publication of his essay.

For Mahan, there were two main implications. Firstly, that the western coast of North America would now be more readily accessible by American fleet elements based on the Atlantic coast and the Royal Navy would be thousands of miles closer to the westernmost provinces of Canada. The ability to provide greater security along that coast would mean that the population of the region could be greatly increased, and the products produced on that seaboard would be able to be reliably traded, with consequent economic gains:

The great effect of the Panama Canal will be the indefinite strengthening of the Anglo-Saxon institutions upon the northeast shores of the Pacific, from Alaska to Mexico, by increase of inhabitants and consequent increases of shipping and commerce.

Mahan’s second major impact would be less direct, but no less significant. He saw that the expansion of populations and industry on the Pacific northeast would produce a ‘correlative effect’ of making the western territories in the Pacific basin (especially Australia and New Zealand) more attractive to Europeans, whose numbers would naturally increase, strengthening western wealth and consolidating its colonial interests—a process he calls the ‘Europeanization’ of the region.

For Mahan, an increase in the number of Europeans in the region would necessarily bolster western sea power as well. He describes what we would call today a ‘positive feedback loop’, in which western sea power would enable greater European populations to flourish, which would in turn support greater naval forces. To his mind, no one did this better than Europeans:

The greatest factor of sea power in any region is the distribution and numbers of the populations, and their characteristics, as permitting the formation and maintenance of stable and efficient governments. Such stability and efficiency depend upon racial traits… As a matter of modern history, this capacity has been confined to nations of European civilization, with the recent exception of Japan.

This is not (just) a regrettable snapshot of Edwardian era thinking about race. It is also, to a good approximation, an accurate assessment of the degree of industrialisation and technological sophistication on the opposite sides of the Pacific at the time. But even given that, Mahan is forced to make an exception and allow that Japan is a special case. Indeed, he could hardly argue otherwise after Japan had soundly defeated the forces of Tsarist Russia in the war of 1905. As Mark Thomson and I argued in a previous ASPI paper, this victory came despite a significant advantage to the Russians in terms of the size of their forces and the level of industrial might they could throw behind the development of them.

At the time of Mahan’s essay, the United States was in the process of increasing its naval weight and presence. Teddy Roosevelt’s ‘great white fleet‘ circumnavigated the globe between 1907 and 1909, demonstrating a blue water naval prowess that the USN has maintained ever since. America was a power on the upswing, a process Mahan was sure would only be enhanced through the opening of the Panama Canal.

Even so, Mahan—possibly with the lessons of 1905 in mind—recognised the limitations of even greatly enhanced American power. This was the sentence I recalled and wanted to put in its proper context: The Western Pacific will remain Asiatic, as it should.

This is a significant concession, given his views on the near-unique abilities of Europeans to marshal resources. His reasoning is apparently based on the populations present—it seems that the large populations of Asia were sufficient to overcome the developmental handicaps that he identified. As he saw it, the real problem was working out where the line was to be drawn:

The question awaiting and approaching solution is the line of demarcation between the Asiatic and European elements in the Pacific. The considerations advanced appear to indicate that it will be that joining Puget Sound and Vancouver with Australia… but there are outposts of European and American tenure in positions like the Marshall and Caroline Islands, Guam, Hongkong…

So, for Mahan, the policy challenge was working out to divide up the Pacific basin between European and Asian powers. Not surprisingly, he thought that ‘naval power, the military representative of sea power, will be determinative’.

Mahan’s thinking—putting to one side the unfortunate racial stereotyping—is germane to deliberations to the future of the Asia–Pacific theatre as well. We have just lived through more than half a century of unusual circumstance in the region following World War II, in which there were no Asian powers able and desiring to compete effectively with western forces. As a result, western analysts have got used to the idea that American naval power is bound to be able to carry the day. But as Asian economic growth—powered in no small way by population size in a way that Mahan would readily recognise—brings more state resources to bear, we are trending back towards a time much more like Mahan’s 1911 environment, in which American power is clearly dominant in the eastern Pacific but things get fuzzier the further west we look.

Even with the growth in Chinese military power over the past couple of decades, the USN would probably win any naval conflict fought in the western Pacific today. It has had decades of head start. Even so, American naval scholars now talk of China being on the verge of a ‘game changer’, and a comparison of the RAND Corporations 2000 (PDF) and 2009 (PDF) studies on a hypothetical Taiwan Strait conflict shows how quickly things can change. And Russia was probably confident of the outcome of the war against Japan a century ago.

The future won’t be the same as the past, but it’s worth thinking carefully about the first principles of power balances. In 1911 an insouciant America was on a growth curve and was set to become the dominant power of the second half of the century. Even so, one of its leading strategists was ready to cede the western Pacific to Asian powers. We’re not at that point now, but I think it behoves us to keep in mind the exceptional nature of recent history and to look a little further back.

Andrew Davies is a senior analyst for defence capability at ASPI and executive editor of The Strategist. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.