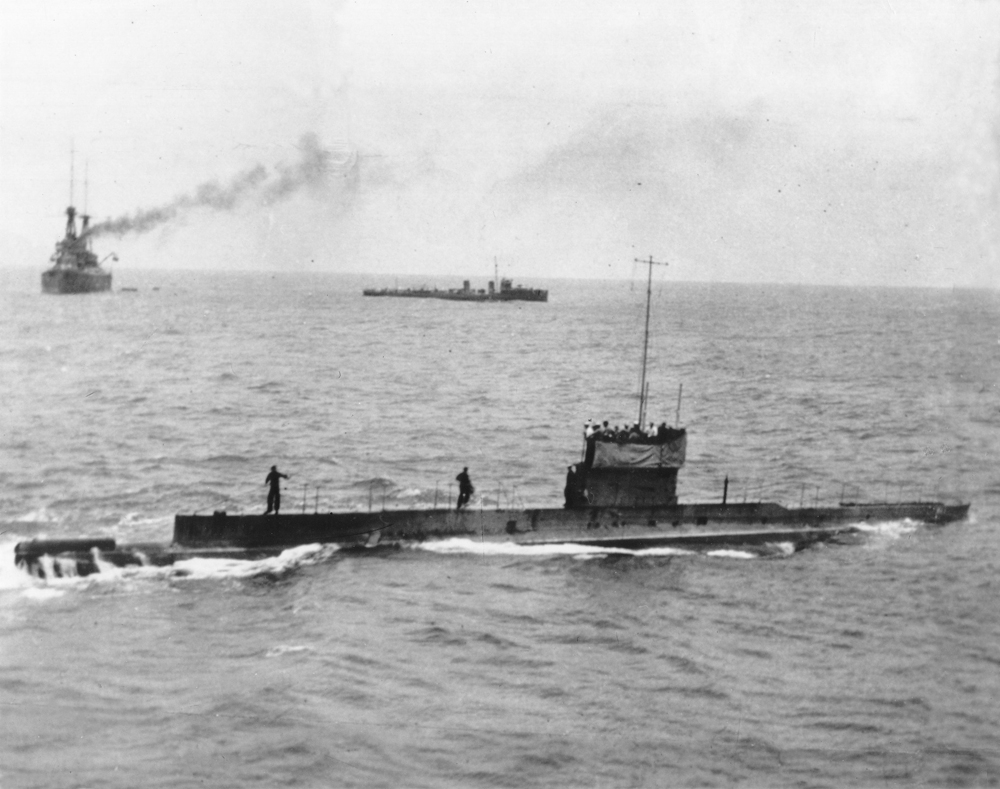

I was pleased to be invited to the Submarine Institute of Australia biennial conference last week, which doubled as a celebration of the centenary of Australian submarines. Australia’s first boats, the AE1 and AE2, were commissioned in early 1914. But a little over a year later both had been lost, AE1 with all hands. Historically, submarine operations have been among the most dangerous of any military activity. Having spent a short time on both Oberon and Collins class boats and having experienced the cramped working environment, let me give a shout out to Australia’s submariners, past and present.

I was pleased to be invited to the Submarine Institute of Australia biennial conference last week, which doubled as a celebration of the centenary of Australian submarines. Australia’s first boats, the AE1 and AE2, were commissioned in early 1914. But a little over a year later both had been lost, AE1 with all hands. Historically, submarine operations have been among the most dangerous of any military activity. Having spent a short time on both Oberon and Collins class boats and having experienced the cramped working environment, let me give a shout out to Australia’s submariners, past and present.

I had a couple of speaking roles at the conference. My main address was on the strategic environment out to 2050. (I’ll come back to that in another post.) But I also took part in the first session on the conference program: a robust panel discussion. We covered some expected ground, such as the much-rumoured ‘Option J‘ and its impact on naval shipbuilding in Australia. But a few things came up that surprised me. Of those, at the top of the list would be the lack of appetite among the panellists for a Collins life-extension program.

One of my working assumptions about the Future Submarine project (FSM) had been that a Collins life extension was likely, if not unavoidable. As Mark Thomson and I showed in 2012, if a new design submarine is required, then there’s a high likelihood of a capability gap unless the replacement boat can be engineered and built relatively quickly—certainly faster than the Collins was. And later that year (also at an SIA conference) Defence said that there were no obvious show-stoppers for an extension program—a conclusion government endorsed shortly afterwards.

But some of the panel participants were adamant that a Collins extension was something to avoid if at all possible. That view seems to have wider currency than I’d have thought, and it was later reinforced by Defence’s General Manager for Submarines, David Gould. He observed that he’d prefer to deliver the FSM without having to ‘give the Collins class another commission’, though he added that ‘we might need to keep them going a little longer’.

Of course, the landscape has changed in the past six months, which might provide an explanation for the apparent change of thinking. The more ambitious—and almost certainly highly bespoke—FSM of the 2009 Defence White Paper has apparently been relegated to a footnote in history, to be replaced by something more modest in scope. Though Admiral Greg Sammut, Head of the FSM Program, pointed out that even the new specs were challenging:

… our requirements in terms of range, endurance and payload do not differ from those that shaped the Collins program. Naturally, we will need improved stealth and sensor performance… We have taken a disciplined approach based on operational analysis to setting requirements for the FSM, mindful of the current state of technology and with a keen eye to the integrated nature of submarine design. In doing so, we’ve readily established that some of the higher-end requirements of the Collins remain challenging to this day…

The focus on stealth and sensors is sensible. The operating environment for submarines is inevitably going to become more challenging, and the evolution in ASW sensors will mandate improvements in stealth. The question, as always, will be how much performance is achievable, and at what cost? In that context, Sammut added (in words that almost brought a tear to my eye and which Augustine would approve) that ‘… we have a much clearer understanding of the cost-benefit capability trade-offs that are guiding our planning at the outset’.

But, overall, there was more that remained unclear than clear after this conference, including the basic question ‘how many submarines’? That’s consistent with the Defence Minister’s comments at our own submarine conference earlier this year. In fact, it became a running joke amongst presenters that one shouldn’t mention the size of the future fleet. And that’s fair enough—until the costs, capability benefits and project risks are well understood, it’d be ill-advised to pick a number.

Equally unclear, though less unspeakable, was the acquisition strategy. There are two quite different options—Japanese, with most of the construction work done offshore, or European (France, Germany or Sweden), with construction there, here or (likely) a combination of both. The various would-be European exporters all had a chance to make a pitch, and did so in presentations very much in keeping with their national characteristics. The newest item was a new submarine concept from French firm DCNS, based on their nuclear-powered Barracuda boat. And the Swedes spoke after throwing their hat in the ring with an unsolicited bid. But, overall, we didn’t learn much new about those options and much of what Mark and I wrote a few months ago remains as good as we’re going to get for now.

Andrew Davies is senior analyst for defence capability and director of research at ASPI. Image courtesy of the Royal Australian Navy.