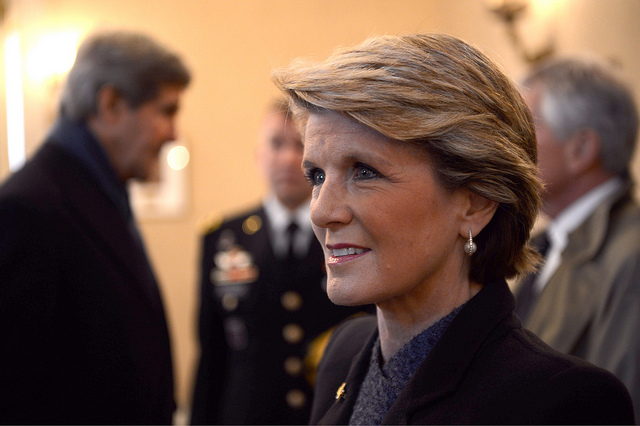

Last week, Foreign Affairs Minister Julie Bishop addressed Australia’s Regional Summit to Counter Violent Extremism, highlighting the increasing role of women as participants in violent extremism and as important agents in counter-radicalisation strategies.

Bishop noted the rising proportion of women—including from the West—in the ranks of the Islamic State (IS). Nearly one-fifth of those involved with IS in Syria and Iraq are female, including over 500 Westerners. Of those, 30–40 are Australian and known to be engaged in or acting in support of terrorist activity, with several involved in the radicalisation and recruitment of other women.

Bishop expressed her disbelief that such large numbers of women are supporting IS ‘given that it is women and girls who are disproportionately affected by the activities of terrorist groups.’ She called for the ‘right voices’ to expose the realities of life on the ground in the Islamic State for women and children, and for a clear recognition that ‘women can be powerful voices against extremist propaganda and the radicalisation of members of their families and communities.’

It’s positive that the role women can play in countering violent extremism (CVE) is now receiving government-level attention in Australia. Policymakers have tended to overlook how women can be powerful opponents of violent extremism and play a significant part in the development and implementation of CVE policies. According to the Global Center on Cooperative Security, women are uniquely placed to detect signs of radicalisation and to intervene early on. Traditional female roles of wife, mother, sister and carer can empower them to ‘challenge extremist narratives and shape the home, education and social environments.’

The idea that women have a strong role to play in CVE is gaining traction. In September last year the United Nations Security Council Resolution 2178 recognised the direct influence that women have in stopping the spread of extremism, encouraging Member States to engage relevant local communities and non-government actors—including women—to ‘counter the violent extremist narrative than can incite terrorist attacks.’

Global initiatives focused on the role of women are also being established. For instance, the UK Metropolitan Police recently launched a campaign to prevent younger women from travelling to Syria and Iraq by encouraging mothers to observe their daughters’ behaviours for early indications of radicalisation. The German Institute for Radicalization and De-radicalization Studies (GIRDS) has established a ‘Mothers for Life’ network that brings together mothers who have experienced violent jihadist radicalisation in their own families and advocates for women to use these experiences to establish strong and convincing counter-narratives. And the US recently hosted a ‘Women and Extremism Summit’ in Washington DC, attended by 25 female leaders, on the roles that women play in extremism and counter-extremism. Bishop’s remarks show that Australia is in line with global thinking on women’s roles in CVE.

However, Bishop’s speech—and mainstream discourse on this issue in Australia more generally—lacks an understanding of the complex and varied push/pull factors that drive women to become involved with IS and groups like it. To date, government statements and media commentary on women in violent extremism have predominately focused on either the ‘jihadi bride’ phenomenon by which women are convinced to offer themselves up to IS fighters, or the extent to which women are exploited by the brutal ‘rape cult’ of IS.

Jayne Huckerby, director of the International Human Rights Clinic at the Duke University School of Law, maintains that while some women are drawn to extremism out of purely romantic inclinations or by the will of another person, many are actually motivated for the same reasons as men: adventure, inequality, alienation and ‘the pull of the cause’. Ignoring these various motivations in favour of stereotypes will limit the reach of any policy designed to counter female violent extremism

Huckerby also argues that there’s an overdependence on the narrative of IS’s brutality towards women to dissuade more women from signing up. Such narratives can actually increase the susceptibility of women to IS recruitment by fuelling the bigotry that leads to Islamophobic attacks against Muslim women and girls. These types of attacks can create feelings of discrimination and disenchantment, along with feelings of identity loss and confusion. Psychological vulnerabilities are readily exploited by IS. According to the Islamophobia Register Australia’s founder Mariam Veiszadeh, there have been a large number of religiously-motivated attacks against women wearing the hijab in recent months.

Nevertheless the Foreign Minister’s address is encouraging; it demonstrates that government and policymakers are becoming more attuned to the extent of female involvement in violent extremism, and how women can be used more effectively to counter the lure of IS. However, there’s more that can be done.

While there’s now a fair amount of research being conducted into the range of factors that lead women to throw their lot in with extremist causes, including most recently by the UK-based Institute for Strategic Dialogue (PDF) and Quilliam Foundation (PDF), it’s not yet clear that the conclusions of this research are being incorporated into policy here in Australia. It’s positive that government and policymakers are looking to the roles that women can play towards countering violent extremism. However, if the reasons why women either actively engage in violent extremism or actively advocate for it are overlooked, the sophisticated propaganda and recruitment campaigns of groups like IS pitched at women and girls will continue to be successful.