Schools are now on the frontline of countering violent extremism (CVE). Last week, the New South Wales government announced a state-wide audit of all prayer groups conducted in public schools following allegations of radical Islam being preached in a Sydney playground.

Premier Mike Baird noted that:

I don’t think any one of us could have imagined four or five years ago the concept of 13- and 14-year-olds being involved in extremism and signing up for terrorist activities. That’s something almost beyond comprehension.

NSW Police will develop training for the education department on radicalisation and extremism. That’s sensible, even though the national counterterrorism blueprint, released last week by the Council of Australian Governments, didn’t mention building resilience in schools.

Fortunately we’re not at the point here of ‘Operation Trojan Horse’ in Birmingham. Peter Clarke, former chief of the UK’s Metropolitan Police’s counterterrorism command, found last year that there was a ‘coordinated, deliberate and sustained action to introduce an intolerant and aggressive Islamist ethos’ into some Birmingham schools.

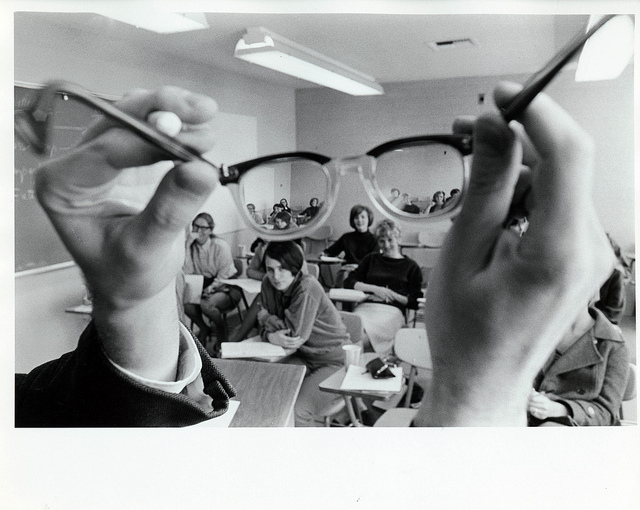

The blunt reality is that both federal and state governments are rarely in a position to observe early signals of radicalisation. It’s the teachers who have regular contact with young people.

Teachers are often best placed to note changes of ideas and behaviour that may indicate that their students are being radicalised and in need of help. They might, for example, hear a student expressing an interest in traveling to a conflict zone overseas with the intent of fighting with ISIS.

So it’s necessary that we raise awareness among those who work in schools about the dangers of extremism. Just as they would do if they detected young people falling prey to social ills like drugs or paedophilia, teachers have a duty to report cases of radicalisation. (A contrary view may be found here.)

However, that’s not to suggest that a few hours of training is going to make a teacher attuned to the complex dynamics of radicalisation. Without sufficient knowledge, well-meaning efforts may produce adverse consequences.

We don’t want our teachers to be too cautious. But on the other hand, we don’t want them to be paranoid or resort to moral panic about the risks of extremism. Teachers will need to refer vulnerable children to a voluntary (although in some cases compulsory) counselling program with strong mentors. To date, we’ve only taken baby steps towards any counter-radicalisation intervention programs, (as opposed to CVE programs targeting communities).

Australian officials might selectively visit schools to dispel any misconceptions about Australian society and provide balanced information on our foreign policy interests in the Middle East and terrorism, rather than students relying on radical online material.

Our state and federal officials working to counter violent extremism should now step up their efforts to work with teachers to raise awareness of radicalisation and violent extremism, paying particular attention to students’ development needs. There’s also, as I’ve suggested before, a role for the Children’s e-Safety Commissioner to raise awareness in schools about the dangers of online extremism.