Russia has made a speciality of integrating its cyber efforts with broader offensives. It’s been refining the practice, as was evident in its invasion of Georgia in 2008 and Ukraine in 2014, and now in 2022.

Cyber is used by Russia to disrupt, if not destroy, digital infrastructure and communications; to sow confusion among the leadership of its adversaries while reinforcing its version of events among its own population and partisans; and to prepare the ground for more conventional forces.

We can also expect Russia to use cyber to retaliate against Western nations and punish others, such as the Baltic states, as a warning. Cyber offers Russian President Vladimir Putin a means of continuing escalation, against which the West has not—yet—a clear, coherent response.

Attribution, which has been argued is an appropriate ‘naming and shaming’ of bad actors, depends on everyone buying in to an existing global order and rules-based system—which Putin has determinedly stepped beyond.

Australia has largely lucked out in avoiding the fallout of earlier Russia attacks, in part thanks to its timezones. In 2017, NotPetya was launched while Australian businesses were closed for the evening, enabling most to take preparatory action for the next day. This time is likely to be different—the world remains highly interconnected and the invasion of Ukraine affects the global order.

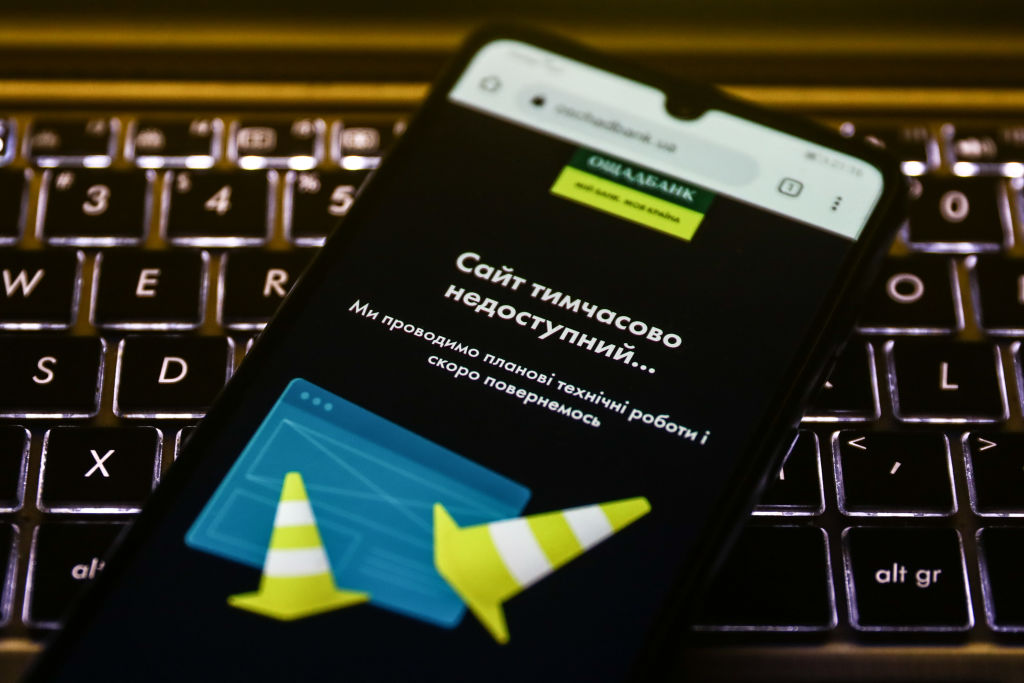

The forms of disruption are likely to be threefold. First, there will be direct cyberattacks. The Ukrainian government and businesses, especially banks, have been subjected to denial-of-service attacks. There’s evidence of Russian use of a data wiper and there are indications that Sandworm, the Russian group that instigated NotPetya, has a new tool to hand. While Australia isn’t in the direct line of fire, it may be targeted as part of retaliatory action responding to sanctions.

Second, there’s the prospect of collateral damage. With the NotPetya attack, most of the damage was incurred by businesses outside Ukraine, when the NotPetya malware entered the wild. In this case, we should expect a wide range of actors—including nation-states and criminal groups—to look to exploit the disruption such attacks may cause, as well as try to utilise the same or similar malware.

Third, there will be more disinformation. Disinformation, or maskirovka, has long been an integral part of Russian military operations. Cyber, social media and fake news offer a broad toolkit for Russian intelligence and military operatives. Much is directed at Russia’s own population, as well as its partisans in Eastern Europe, and is used to justify its activities and hide bad news. But as we’ve seen in the United States and elsewhere, it’s used to sow dissent and disruption in democratic societies too.

To that end, the advice from the Australian government to follow the Australian Cyber Security Centre’s guidance is useful but only a start, and directed largely at the technical elements of organisations. A wider level of business preparedness is needed that recognises the prospect of broader disruption: individual companies may not be affected, but their supply chains, service providers and financial services, among others, may be.

Organisations should not wait for the government to step in. It has limited capacity and we would expect most of its skilled staff will be focusing on the government’s needs, should Australia be subject to a sustained attack.

Organisations know their own business better than governments, so they will be best placed to make judgements about business continuity, critical data, supply chains, customer needs and the nature and pace of their operations. As most of their technology is sourced, built or controlled from overseas, that’s where patches, reconfigurations and rebuilds will come from.

That leaves small businesses particularly exposed. Because of the indiscriminate nature of the threat, it’s in the interests of large businesses with more capability—and industry groups—to assist small and medium-sized enterprises. After all, NotPetya was launched through a firmware update to accounting software built by a blameless Ukrainian software firm. Every modern business has such dependencies and interconnectedness.

As ever, it’s best to be prepared, and businesses should consider potential effects on their operations in the event of disruption—but also prospective delays due to Covid-19.

In many regards, we now are in uncharted territory. Attribution is useful but has little deterrent effect. Russia’s behaviour will encourage others. Putin has an escalation ladder that, potentially, may harm civilian infrastructure, businesses and populations more than military capabilities. The West will need to ensure it preserves its freedoms, wellbeing and systems while managing a direct threat to the existing system of nation-states and to democracy.