Yesterday saw the launch of the ANAO’s 2012–13 Major Projects Report, which takes an auditor’s eye view of the biggest and most complex defence projects. This year it analyses 29 projects—more than previous, and making this an increasingly rich source of data for those of us who worry about these things. We at ASPI will no doubt dip into this compendium frequently in the months to come, but for now a quick overview will have to do.

Yesterday saw the launch of the ANAO’s 2012–13 Major Projects Report, which takes an auditor’s eye view of the biggest and most complex defence projects. This year it analyses 29 projects—more than previous, and making this an increasingly rich source of data for those of us who worry about these things. We at ASPI will no doubt dip into this compendium frequently in the months to come, but for now a quick overview will have to do.

The report has already made headlines. The Australian yesterday ran a story about the state of the Air Warfare Destroyer project and worried that there might be as much as a $1 billion cost blowout and possible further schedule delays. That’s not directly borne out from the audit report—although a careful reading suggests that potential future troubles loom.

But first, here’s what the report said. The project summary for the AWD program (written by the DMO) notes that it:

… exceeded the budget allocation in Financial Year 2012-13 as a result of increased [costs] from the industry participants for labour, materials and sub-contract costs. Against the original budget, the total was exceeded by $106.4m, but was within the revised budget… the DMO considers, as at the reporting date, there is sufficient budget remaining for the project to complete against the agreed scope.

The auditor’s relatively sanguine report produced a rare thing in the form of an Opposition press release that hailed the virtues of a Defence project. That said, the audit report makes clear that the overspend in the last reporting year wasn’t a result of accelerated work (a good thing) but rather reflected a blowout in the cost of inputs (a bad thing). It points to some problems which, if left unaddressed, mean that future overspends can be expected. These include the challenges of (page 150):

- achieving maximum productivity levels through efficient shipyard operation and change management

- managing the level and timing of changes to the production baseline to minimise production rework

- meeting the consolidation, test and activation schedules for Ship 1 within the constraints of a new build in a new Australian shipyard

- managing the timely delivery of equipment and fittings from a large number of subcontractors located in Australia and overseas through the AWD Alliance and

- delivering an effective, efficient and sustainable through-life support system for the Hobart Class DDGs.

In fact, the ANAO report and The Australian’s story can both be true at the same time. Shipyard productivity levels and the performance of sub-contractors contributed directly to this year’s budget overspend. If that continues, the project could well consume its so-called ‘contingency’ funds—that part of the approved budget put aside for the unexpected—and then require additional funds. Other reasons to worry about the AWD project are the incentives for various players under the alliance model (which aren’t always aligned with the taxpayer’s interest) and any temptation that might exist to slow down delivery to keep the yard active through the so-called ‘valley of death‘. That could only add to the cost as well as further delaying delivery.

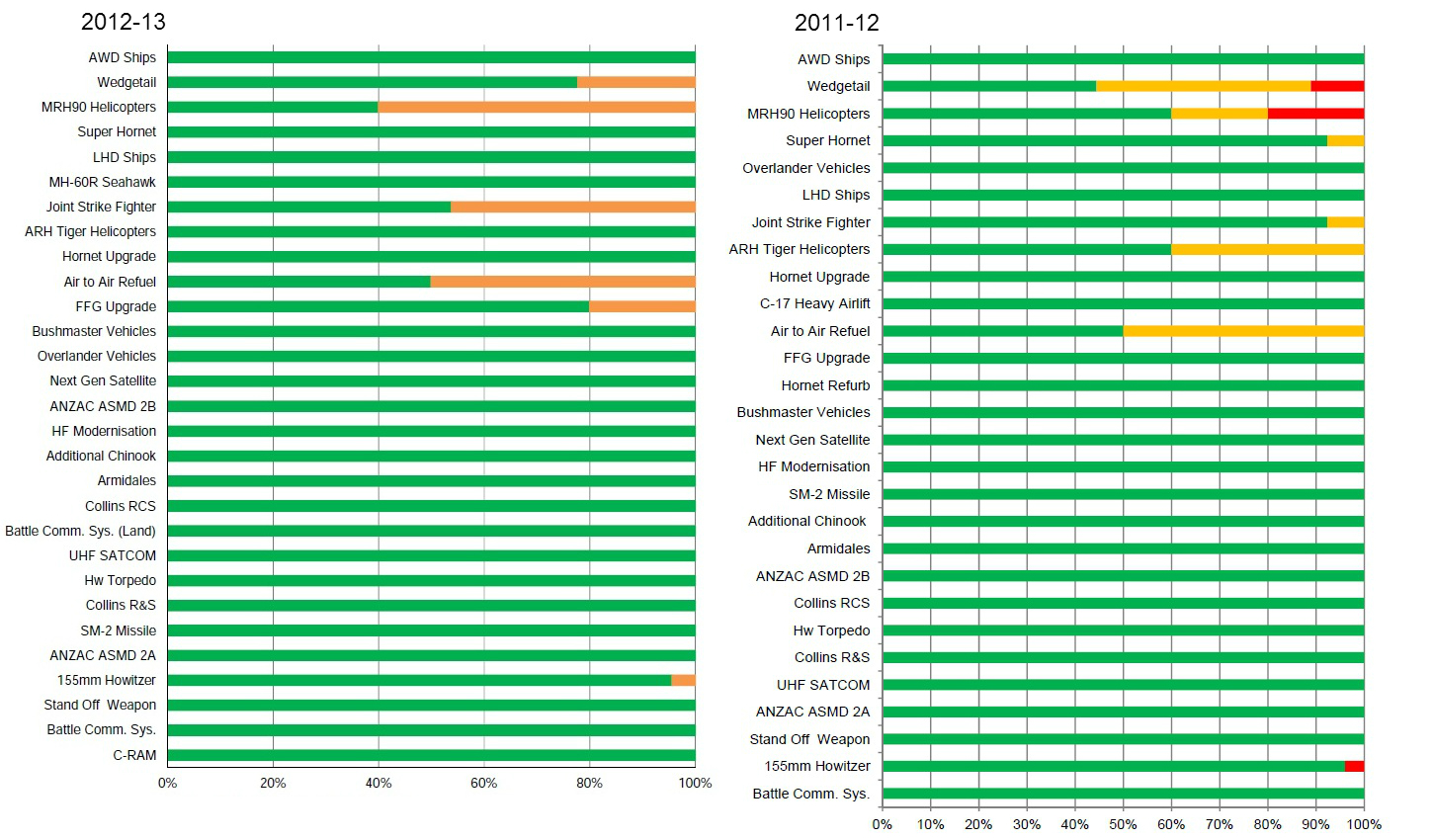

But there’s also some good news; at least the AWDs are on track to meet all of the performance requirements, and will exceed some of them, according to the DMO’s assessment. Of course, that’s an assessment ahead of the actual physical integration of the vessels combat system, weapons and sensors. Nonetheless, the expectation is consistent with the performance of several other major projects in the portfolio. Shown below is figure 13 from this year’s report (left), with the corresponding figure from last year’s (right) for comparison. They show the expected percentage of capability to be delivered, with an estimate of the associated uncertainty. Green = ‘materiel capability likely to be met’; amber = ‘materiel capability under threat, but considered manageable’ and red = ‘materiel capability unlikely to be met’. (Click to enlarge diagram)

The effect of remediation efforts in some of the troubled projects is clear from this comparison. There are no capabilities now considered ‘unlikely to be met’, and two aircraft projects in the form of the Wedgetail airborne early warning and control platform and the Army’s Armed reconnaissance helicopters have made substantial progress. But of note is the fact that fully half of the Joint Strike Fighter capability is now flagged amber, compared to just 8% last year. That’s something we’ll have a much closer look at in 2014 as the second pass decision looms.

But by the ANAO’s accounting, 95% of the promised capability portfolio will be delivered with high confidence, with 5% being under closer management. The new report has a longitudinal study that looks at data over the six years the ANAO has been compiling this report, and the improvement over time has been steady. This suggests that the DMO is getting on top of some of its project management woes.

Less encouraging is the data on project schedules. The ANAO again provide a longitudinal analysis (page 22), and the table below summarises the schedule data. Former DMO CEO Stephen Gumley commented that it was schedule rather than cost or capability that worried him most. By the look of this data, his successor Warren King is probably thinking pretty much the same thing. But I’d just caution that it’s often industry, not DMO, that’s the cause of that underperformance.

|

2010–11 |

2011–12 |

2012–13 |

|

| Number of projects |

28 |

29 |

29 |

|

Schedule slippage (total) |

760 months (31%) |

822 months (30%) |

957 months (36%) |

| Average schedule slippage per project |

30 months |

30 months |

35 months |

| Schedule slippage (in-year) |

72 months (3%) |

99 months (4%) |

147 months (5%) |

Andrew Davies is senior analyst for defence capability at ASPI and executive editor of The Strategist. Image courtesy of Brian Burnell photography, under creative commons license CC-BY-SA-3.0.

Correction: an earlier version of this post incorrectly attributed the quoted comments on the AWD project to the ANAO. The project summaries in the report are entirely authored by the DMO.