It’s difficult to make predictions, especially about the future. This is particularly the case with the trajectory of GDP growth.

That’s one of the problems with tying defence funding to a specific percentage of GDP, whether it’s 2% or some other number. As official predictions for GDP growth change, the Defence Department’s future funding changes. This means that the future force structure is constantly changing as defence planners try to match capability with changing dollars. In the force structure planning that led into the 2009 white paper, entire fleets were created and destroyed on paper in response to adjustments in the Treasury’s predictions for GDP growth. That is, until the government agreed to a firm funding model and Defence matched its capability aspirations to that level of funding.

Unfortunately for Defence, in 2009 the global financial crisis prompted Prime Minister Kevin Rudd to initiate large-scale stimulus spending, and the defence funding model was changed before the ink was dry on that white paper. And a few years later, in an ultimately unsuccessful attempt to pay back the borrowing necessary to fund the stimulus and return to surplus, the government further cut spending. Since funding cuts always hit the capital program hardest, this resulted in large numbers of delayed and scaled-back projects.

One of the good aspects of the 2016 defence white paper was that it contained a fixed funding line for the subsequent decade that Defence could plan to. And, as I’ve noted, the government has delivered that funding.

However, round numbers resonate, so public and media attention has focused on the government’s other funding commitment in that white paper, which was to increase Defence’s budget to 2% of GDP by 2020–21. Based on the 2019–20 portfolio budget statements, that will happen, although we won’t know for sure until Defence’s accounts for 2020–21 are all done and dusted sometime in late 2021 or early 2022.

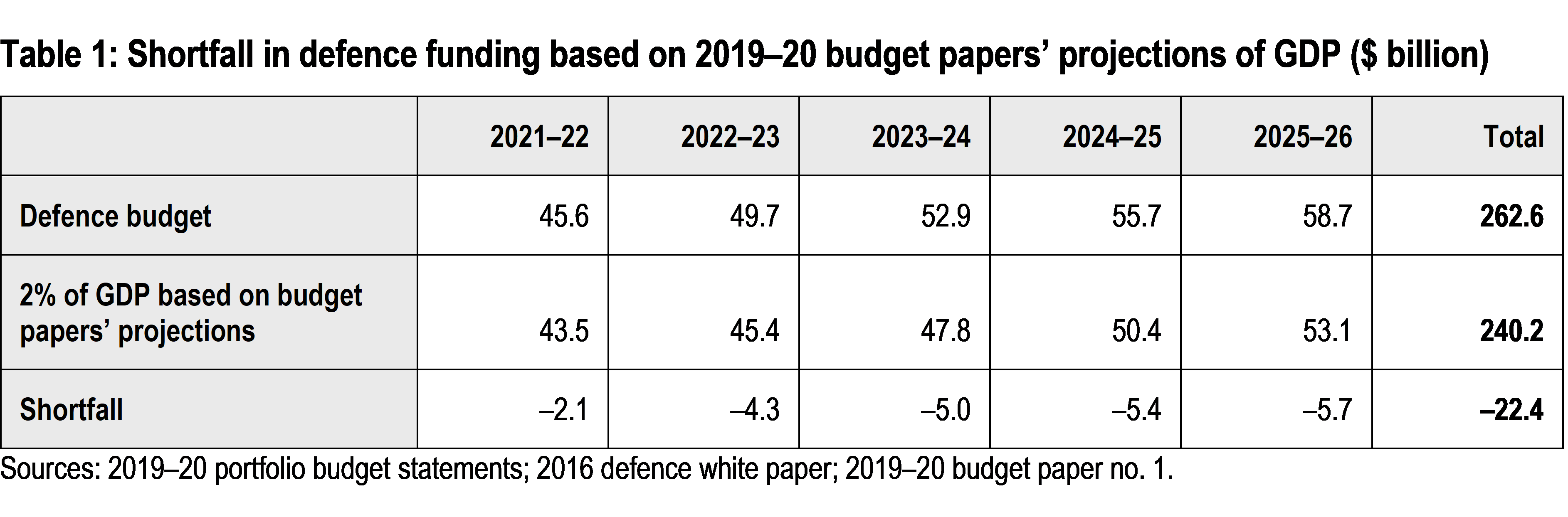

It’s important to note that the commitment didn’t set Defence’s funding at 2% beyond 2020–21. That funding was to be provided by the fixed funding line. As I explained in ASPI’s 2019–20 budget brief, the fixed funding line exceeds likely projections of a 2% of GDP funding line. How much it exceeds it by depends on the assumptions you make about GDP growth. In the budget brief, I projected out the 2019–20 budget papers’ GDP growth predictions to come up with the gap between the two over the second half of the white paper’s funding decade (Table 1).

That would result in an annual shortfall of around $5 billion by 2023–24 and a cumulative shortfall over the second half of the white paper decade of over $22 billion. That’s more than the entire cost of the F-35 project (remember what I said about entire fleets being created and destroyed based on changing GDP predictions).

That growth rate is pretty consistent with Australia’s historical performance going back to the global financial crisis, which is around 4.7% nominal average annual growth (meaning real growth plus inflation). So, if you’re a glass-half-full kind of person, the assumption’s reasonable.

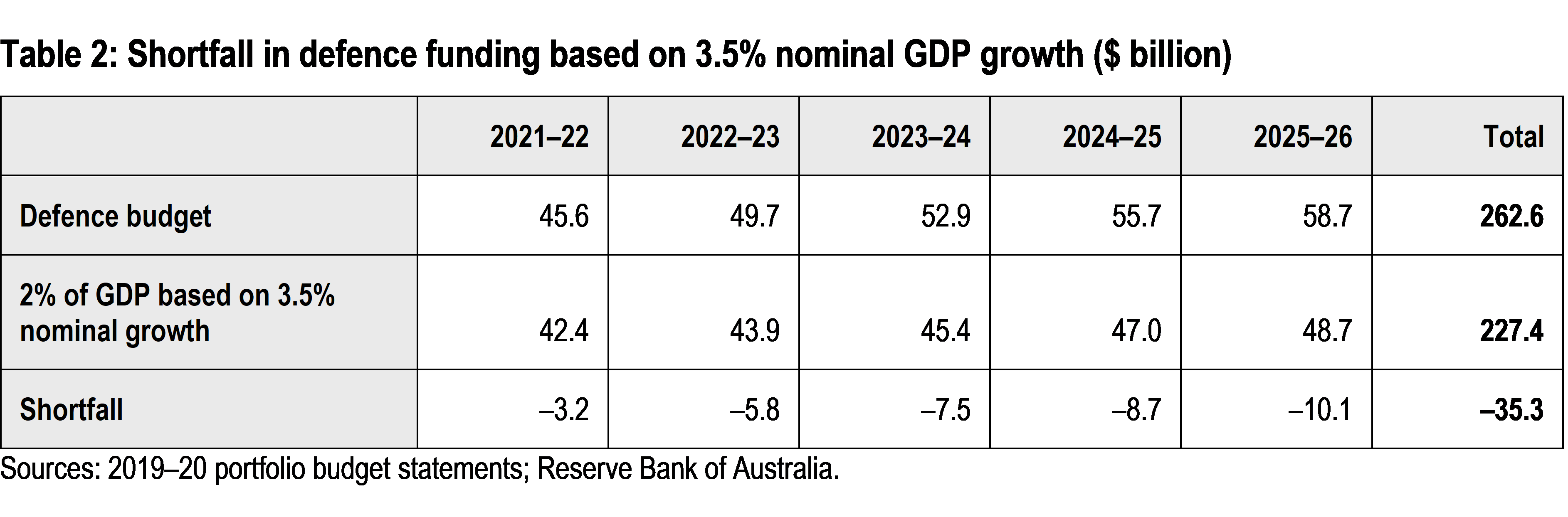

But in May this year the Reserve Bank of Australia put nominal GDP growth for 2018–19 at 3.5%, so if you’re a glass-half-empty kind of person and think that GDP growth has stalled at that level, then the shortfall gets much bigger—around $35 billion over the second half of the decade (Table 2). That is several fleets’ worth. In that scenario, the government would need to spend 2.4% of GDP just to deliver the white paper funding. That sort of projection is probably a worst-case scenario (hopefully). But short of economic miracles, the white paper’s fixed funding line is going to substantially exceed any 2% of GDP line. For them to align, average annual nominal GDP growth of around 5.5% would be needed, a much better result than Australia has managed over the past decade. In light of the copious analysis that suggests GDP growth is being driven largely by immigration rather than by enhanced productivity, sustained nominal growth of 5.5% seems unlikely.

That sort of projection is probably a worst-case scenario (hopefully). But short of economic miracles, the white paper’s fixed funding line is going to substantially exceed any 2% of GDP line. For them to align, average annual nominal GDP growth of around 5.5% would be needed, a much better result than Australia has managed over the past decade. In light of the copious analysis that suggests GDP growth is being driven largely by immigration rather than by enhanced productivity, sustained nominal growth of 5.5% seems unlikely.

Should GDP growth stall, government revenue will as well, so there will be more intense competition for funding. In short, it may well become attractive for a future government to provide something closer to 2% and declare its commitment met. To be fair, the government hasn’t hinted at that, although its own statements consistently refer to the 2% commitment, not the larger white paper funding line. But the temptation will be there.

In the next part of this series, I’ll look at whether 2% of GDP is commensurate with Australia’s historical spending on defence in periods of strategic uncertainty.