Transaction, not stability, has always been the defining feature of Australia’s bilateral relationship with China, placing hard limits on its development.

While not advertised at the time, China’s 2013 commitment to an enhanced framework for bilateral discussions with Australia based on annual leaders’ meetings was what Canberra got in return for agreeing to term the relationship a ‘strategic partnership’, just as finalisation of the China–Australia Free Trade Agreement a year or so later was our reward for agreeing to upgrade that designation to a ‘comprehensive strategic partnership’.

Ten years on, against the backdrop of the possibility of annual leaders’ meetings being reinstated following Foreign Minister Penny Wong’s December talks with her Chinese counterpart Wang Yi, it’s worth thinking about what Australia has gotten out of the leaders’ meetings to date and how they could work better for us.

Thinking back to the inception of the enhanced bilateral architecture, President Xi Jinping, then new in the role, would have valued the ‘strategic partner’ and ‘comprehensive strategic partner’ labels for what they said to others about Australia’s strategic trajectory, and he was likely happier than we thought to pay the price of improved market access and a few meetings between Premier Li Keqiang and an Australian prime minister to send that message.

Simply put, China immediately got what it wanted out of the arrangement.

Today, while the comprehensive strategic partnership and free trade agreement remain in place, the bilateral relationship is defined by economic coercion and an aggressive Chinese government that until recently refused to talk to anyone at any level of the Australian government about anything.

The enhanced bilateral architecture clearly didn’t turn out to be the coup for Australia that we thought it was going to be in 2013, and I don’t think there is even one area in which it has had an enduring positive impact on the development of bilateral ties.

We did not get what we wanted.

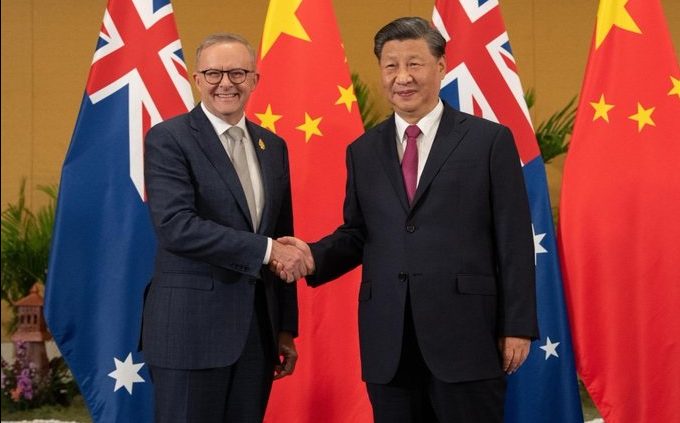

To be worth Australia’s while, reinstated leaders’ meetings would need to be about more than photo opportunities and other mechanical gestures that can imply deference or at least signal improved ties on China’s terms. If they become an annual exercise in Beijing intimating that it has done Australia a favour by talking to us, for which we are then in its debt, then we shouldn’t bother turning up.

We should also not participate if there are conditions attached.

While there’s no price worth paying to reinstate talks that do nothing for us, talks based on a genuine exchange of views about an unlimited range of issues would be incredibly valuable for Australia, and we should make that clear to China.

One way to show Beijing that we want more meaningful dialogue is to initiate one. And in the leaders’ meetings context that means prioritising what it is we want to know over what it is we think China’s leaders want the meetings to say about the state of the bilateral relationship.

We can and should ask questions about matters that interest us and that we think we would benefit from knowing more about, not just ones that allow us to say in a post-meeting press release that subjects x and y were raised.

Presumably, for example, the Australian government would like to know if China’s leaders have been surprised by how ineffective trade sanctions have been in terms of shifting Australia’s strategic calculus, what drove the prolonged period of hyperaggressive global Chinese diplomacy, and how successful they thought it was.

Why not ask? What’s the worst that can happen?

The responses from China’s leaders would be instructive no matter what. If they are dismissive, then they are dismissive. But if they provide considered answers, that would invite us to talk more openly and honestly about our strategic intentions, something we haven’t done enough of with China, often but not always through no fault of our own.

In signing on to the enhanced bilateral architecture in 2013, Prime Minister Julia Gillard said, ‘Naturally, new architecture will not do the work for us or make hard problems in our relationship easy.’ It was, she said, all about ‘elevating existing habits of dialogue and cooperation’.

Then and now, the stark reality of the bilateral relationship is that habits of dialogue and cooperation that cultivate respect, listening skills and an ability to compromise have never been developed between the two countries. And one of the main reasons for that is the transactional nature of the relationship.

The challenges both countries face require more open and effective forms of communication than we’ve been able to develop to date. Using reinstated annual leaders’ meetings to promote a more genuine and inquisitive exchange of views would make it truly worth our while.