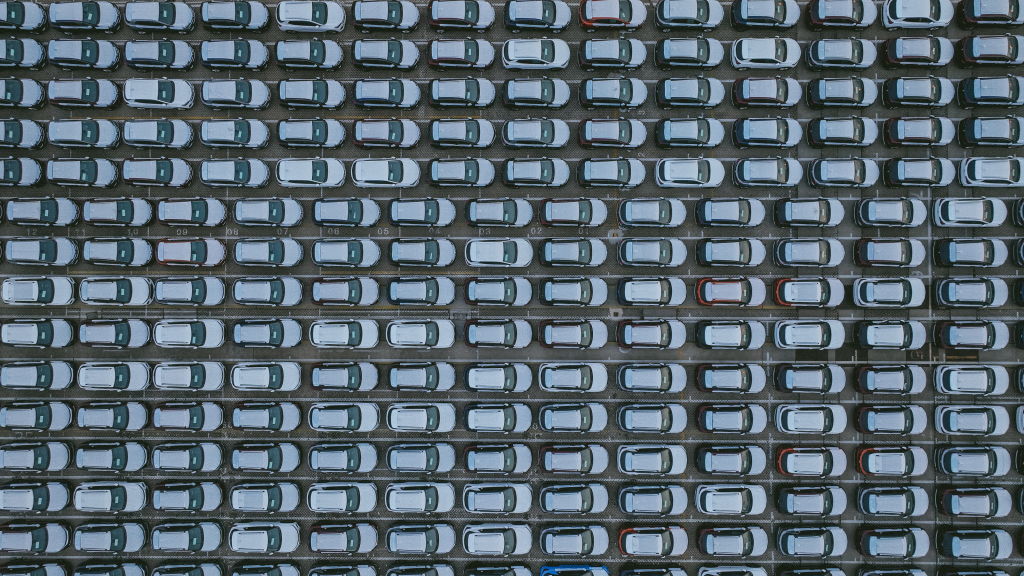

The news that China was the fourth largest source of car imports to Australia in 2022 would have come as a surprise to all but the closest observers of the automotive industry. Behind only Japan, Thailand and South Korea, sales of Chinese-made cars were up 61% on their 2021 figure to almost 123,000.

The milestone marked another step in the remarkable rise of Chinese-made cars, which now represent more than one in 10 sold in the Australian market. As recently as 2018, China was the 11th largest source of passenger and light commercial vehicles for Australia, with just over 10,000 vehicles sold. Since then, it has overtaken traditional major players like Germany and the US, and in some months last year was also ahead of South Korea.

While brands like MG, Great Wall Motor, Haval and LDV have become common on Australian roads, it’s not only Chinese manufacturers leading the charge. Australian-delivered Tesla and Polestar electric vehicles are also made in China. And while Australia is often derided as a laggard in the uptake of EVs, Tesla’s Model 3 outsold the long-popular Toyota Camry last year to take the top spot in the mid-sized car segment. Last month it was the third most popular vehicle in the country, behind only the Toyota HiLux and Ford Ranger utes.

Tesla may have had a head start in the EV market, but other makers are already catching up, with Chinese brand BYD already in second spot in Australia’s small but fast-growing EV market. In fact, every one of the top five electric cars sold in Australia in February was made in China. Overall, 6.8% of vehicles sold in the month were electric, while the total number of EVs and plug-in hybrids on Australian roads almost doubled over the course of 2022.

So, why does any of this matter? As cars have become more technologically advanced, they have turned into what are essentially rolling computers. Modern cars are swathed in cameras and sensors and increasingly connected to the internet for ‘over the air’ tasks like updating software. They collect data ranging from location and routes driven to phone contacts and calls made by drivers. Such data could be used to put together a comprehensive picture of a person’s activities, and, if a car’s owner drives to work at a secure facility, for example, potentially pose a risk to national security.

Researchers and hackers have already shown that they can remotely stop the engines and lock and unlock vehicles made by numerous manufacturers, while others have tracked vehicle locations and gathered drivers’ financial details.

The data-heavy trend is only accelerating with the rapid uptake of EVs and development of self- and assisted-driving technology. As with any internet-connected devices, cars should come under scrutiny for the security of their systems—and arguably more strict examination since there are literally lives at stake when it comes to the fallibility of self-driving technology.

Tesla has been the subject of a number of lawsuits, the latest launched in the US last week alleging that the company and CEO Elon Musk overstated the safety and efficacy of its ‘autopilot’ and ‘full self-driving’ systems over several years, creating a ‘serious risk of accident and injury’. It comes after Tesla recalled 362,000 vehicles in the US after the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration found that the beta version of its full self-driving software (not available in Australia) could increase the risk of a crash.

As Wired reported last year, China has banned Teslas from the streets of certain cities for major communist party events, as well as military bases and other locations, out of what’s thought to be concern that the vehicles’ data could be exploited. Beijing has now banned automotive companies from sending that data outside of China.

‘While keeping that data in China significantly heightens the likelihood that it could be used by state security services, Tesla quickly acquiesced to the new rules last year, opening a dedicated data center on mainland China to satisfy the regulations,’ the Wired report said.

It’s unclear what the implications of Tesla data being held in China might be for Australian drivers, but concerns have already been raised that it would fall under China’s 2017 national intelligence law, which compels Chinese citizens and companies to aid the country’s spy agencies if asked.

Reports that ‘tracking devices’ containing SIM cards were found in sealed components in UK government vehicles have highlighted concerns about the prevalence of Chinese-made parts in the wider automotive industry. Such devices could allow a vehicle’s location to be tracked and would have gone unnoticed had searches not been conducted.

Almost all major car companies source parts from China and some, including BMW, Volkswagen, Volvo, Jaguar and Land Rover, have reportedly worked with China Unicom, which is banned in the US, to develop 5G vehicle connectivity.

As ASPI’s Critical Technology Tracker has found, China is already a leader in many of the technologies that will be vital to the future of transportation, including electric batteries and the analytics and artificial intelligence required to process the huge amounts of data vehicles collect and, in time, integrate them into so-called smart cities.

The Chinese car industry has also been linked to forced labour in the Xinjiang region. Authorities are thought to have detained a million Uyghur and other Muslims there since 2017 and, among abuses the UN has found may constitute crimes against humanity, have forced many to work in industries including the production of car parts, tyres and batteries. Volkswagen produces cars for the Chinese market in Xinjiang and has come under fire for maintaining a presence there, though the company says it has seen ‘no sign’ of forced labour in its plants.

With a wide range of new electric and conventional vehicles coming on sale, China is only likely to increase its market share in Australia in the short term. Much in the same way that crash-testing standards are developed, it’s up to parliament and regulators to implement guidelines that will keep drivers safe on the road—and that means ensuring that cars and their increasingly connected systems are as protected as possible from compromise. Consumers also need to be aware of the potential risks to themselves, their families and their data, and consider whether a vehicle that’s made in China—regardless of the manufacturer—is something they are willing to lay down their hard-earned cash for.