Originally published 24 November 2020.

Three weeks after Americans went to the polls, the morass of conspiracy theories and disinformation surrounding the election and its results continues to grow. Although the US is half a world away, Australians don’t have the luxury of watching this maelstrom as uninterested observers.

The conspiracy information ecosystem is highly international, and here in Australia conspiracy groups are often dominated by narratives and content emerging from the US. As the conspiratorial tidal wave swamps America, ripples are already reaching Australia—and are likely to have implications for our own elections in 2022.

Since around mid-March, Australians have witnessed incredible growth in the spread of conspiracy theories. While this content has spread largely online, conspiracy-fuelled anti-lockdown protests and arrests around the country, particularly in Melbourne, have demonstrated its ability to translate into unrest and conflict in the offline world.

Many of these conspiracy theories originate in the US. Even the most cursory glance through the major Australian conspiracy groups turns up a plethora of content related to US politics. Both the QAnon and sovereign citizen conspiracy theories that have played a prominent role in Australian anti-lockdown protests started in the US and have since spread around the world.

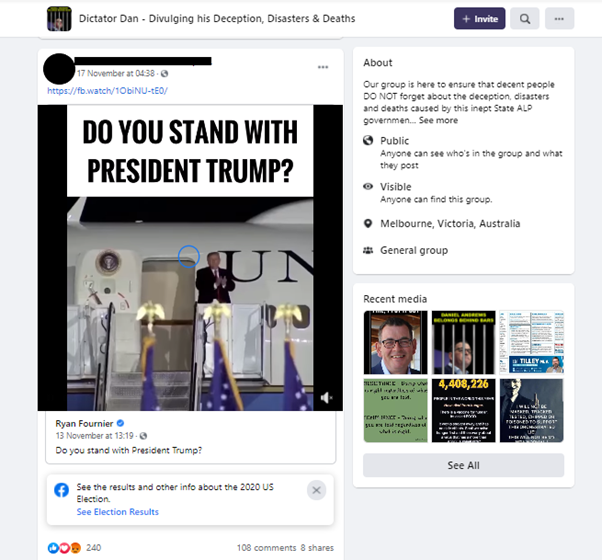

Screenshot of pro-Trump content shared in Australian conspiracy Facebook group targeting Victorian Premier Daniel Andrews.

Support for President Donald Trump in defiance of his election loss has even manifested itself in the form of skywriting over Sydney touting false claims of voter fraud. There was also a small pro-Trump protest in Sydney, which organisers reportedly claimed was not linked to Falun Gong, despite the simultaneous Falun Gong rally being held metres away and the copies of the Epoch Times being handed out to the pro-Trump protesters. According to the New York Times and others, Falun Gong and the Epoch Times have helped to promote a range of pro-Trump conspiracy theories.

Variants of the conspiracy theory that the US voting system was hacked by the CIA, which have been directly and repeatedly promoted by Trump himself, have also expanded to include Australia. US conspiracy theorists have claimed that the CIA used the same technique to manipulate elections in other countries around the world, including Australia.

Screenshot of YouTube video promoting the conspiracy theory that countries outside the US have also had elections hacked by the CIA.

All of this goes to show that while Australians may not be the intended targets of the conspiracy theories swirling about the US election, some of it amplified by the current president and his team, Australians are nonetheless being swept up and carried along on the tide of disinformation.

Australian policymakers and political leaders alike should be paying attention. In much the same way that the confluence of conspiracies between the US and Australia means that triggering events such as bushfires spark the same conspiracy theories, we should assume that the conspiratorial storm lashing the US’s electoral process will have implications for our own elections in 2022.

These conspiracy theories will undoubtedly manifest in different ways. Differences between Australian and American voting systems, such as Australia’s use of paper ballots and pencils, will make some conspiracy theories such as hacked voting machines or SharpieGate difficult to maintain, even for those with only a loose attachment to reality. The thing about conspiracy theories is that they are almost infinitely malleable, however. They will adapt to the Australian context.

We may, for example, see claims that computers into which vote counts have been entered have been hacked, or that mail-in votes have been ‘stolen’. We will almost certainly see conspiracy theories about George Soros, a favourite bogeyman of many fringe right-wing figures, as some sort of sinister hidden hand behind the Australian Greens, activist group GetUp! and potentially the Australian Labor Party.

We should probably anticipate that the growing nexus between the fringe right-wing and fringe anti–Chinese Communist Party actors—perhaps best exemplified by the alliance between Steve Bannon and Guo Wengui—will lead to particular individuals or groups being falsely accused of being agents of Chinese influence or somehow under the sway of the CCP, or that the election has been ‘hacked by China’. Such fabricated allegations and smear tactics may muddy the waters, making it more difficult for security agencies to investigate any real efforts at interference.

It’s unlikely that the tenor of the conversation in Australia’s elections will reach the fever pitch of the current US debate, in which one poll found 52% of Republican voters incorrectly believe that Trump is the rightful winner of the election. A major contributor to this widespread disinformation is the complete abdication of responsibility by the Trump administration and many Republican leaders to state clearly and unequivocally that Joe Biden has won the election.

You’d hope Australian politicians from all parties would not be so profoundly negligent, or prove to have such a weak commitment to democratic values and processes. However, there are some worrying signs. Some high-profile Australian public figures have appeared to give credence to Trump’s baseless claims of electoral fraud.

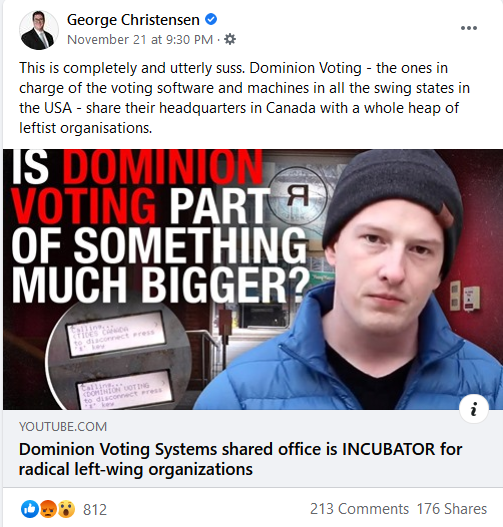

At least publicly, the government has been slow to respond or to stop even its own MPs from spreading conspiracy theories. On 21 November, for example, George Christensen posted a video to his Facebook page on the groundless, technologically incoherent conspiracy theory targeting the Dominion Voting system.

Screenshot of Facebook post on George Christensen’s official Facebook page.

Conspiracy theories are corrosive. They erode trust and confidence, in this case in some of the most crucial systems and institutions which uphold democratic societies. At this very moment, we are witnessing the damage which failing to address this problem when it was smaller and (somewhat) more manageable is doing to the US. The polarisation, mistrust and political gridlock which will arise as a direct result from conspiracy theories and disinformation spread during this election will harm the US both domestically and on the international stage, and it will take many years to rebuild the faith of millions of Americans in the basic democratic processes of their nation.

This is not a road Australia wants to go down. There are steps we can take now to help us avoid it. This includes building trust in the electoral system through awareness campaigns to educate the public on the voting process, how their votes are counted and what steps are being taken to ensure systems are secure.

Perhaps most importantly, however, it means speaking out swiftly, strongly and publicly against purveyors of conspiracy theories and disinformation about elections—regardless of who they are, or which party they belong to.