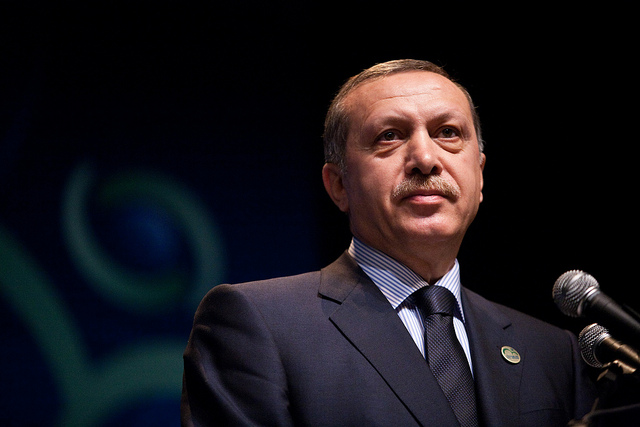

President Recep Tayyip Erdogan of Turkey proved once more this week he’s in a league of his own, securing a thumping victory for his neo-Islamist Justice and Development party in Sunday’s re-run of June’s general election, which had left the AKP without a majority for the first time since 2002 and the country with a hung parliament. With this latest victory in his long string of election triumphs, which not even the ruling party was expecting, Erdogan towers above his rivals.

Unhappily for Turkey, however, in over a dozen years in power Erdogan has come to confuse an absolute majority with his own absolutist rule. And he won in damaging part through polarisation tactics that have left the country deeply divided, at a time when the ethno-sectarian rifts tearing Syria and Iraq apart are spilling into Turkey.

From shortly after June’s inconclusive result, the main issue Turks were confronted with was violence. Fighting resumed between security forces and insurgents of the Kurdistan Workers party (PKK) after a long lull, and Isis bombers struck inside Turkey, most savagely with last month’s suicide attack on a Kurdish peace rally in Ankara, which killed 102 activists. The PKK, for its part, tore up a two-year ceasefire and attacked police and the army. This, it said, was in reprisal for government complicity in ISIS bombings of Kurdish targets.

Erdogan could scarcely believe his luck. He lectured the nation that this was the unhappy consequence of voters straying from the safety of single-party rule—and launched a military offensive, targeting the PKK and Kurdish activists more than Isis. Yet his real targets were electoral.

It was June’s electoral breakthrough of the People’s Democratic Party (HDP), a pro-Kurdish coalition that won over liberal and leftist opponents of Erdogan’s autocratic ways, that temporarily thwarted Mr Erdogan’s plans for one-man rule. Now, in a climate resembling a state of siege, the president fished for Turkish nationalist votes and, by tarring the HDP as PKK terrorists, worked to push down the Kurdish nationalist tally. He succeeded. The AKP won two million votes from far right nationalists, and an estimated one million of the religious Kurds who went with the HDP in June.

He gambled on confrontation and he won. Though constitutionally obliged to be a non-partisan president of all citizens, Erdogan has ruthlessly sharpened the Sunni, Islamist, and ethnic Turkish identity of the AKP and its constituency, ‘othering’ large minorities of ethnic Kurds and quasi-Shia Alevi, and dismissing the secular middle class of western and coastal Turkey as foreign and disloyal.

This at times makes the AKP sound like a neo-Ottoman Tea Party with a sickeningly sectarian stink. But it obscures something real that Erdogan has just shown Turkey and the world once again: his almost preternatural rapport with the adoring Anatolian masses—generally pious and conservative, often dynamic and entrepreneurial, and given access for the first time to modern schools and clinics, roads and airports, through the AKP.

The election result reflects the disconnect between the AKP’s Turkey, and scattered opponents struggling to find a credible alternative to Erdogan. Last month, for example, when Angela Merkel visited Erdogan—proffering a tawdry package of sweeteners to persuade Turkey to act as a holding pen for Syrian refugees streaming into Europe—the

German chancellor and Turkish president were pictured sitting on ornate, throne-like seats in an Istanbul palace that housed one of the last Ottoman sultans. This occasioned much merriment among the twitterati of Istanbul and Ankara. But Erdogan’s Anatolian heartland, impenetrable to his secular opponents, gets its news from TV stations now almost wholly in the grip of the AKP. What they saw is Europe’s foremost leader paying due court to their 21st Century sultan.

Indeed, at the heart of Turkey’s Erdogan problem is the way this president has used and abused state power, as well as control of public contracts and punitive tax audits, to dominate the media, purge dissident voices, and clamp down on social media.

Hundreds of journalists have lost their jobs, scores more are being charged with defaming the president. AKP mobs and trolls now openly menace independent media, while pro-AKP media meanwhile routinely smear opponents, real and imagined, mimicking the pugnacious and paranoid style of their leader. Executives from the traditional business elite describe how it paints them as ‘native agents’ of foreign powers, while Erdogan rails xenophobically against what he calls Ust Akil or ‘a mastermind’—the meta-agenda of a tentacular international conspiracy to bring him down. In the hands of the AKP’s stable of pens-for-hire, this narrative is starting to sound quasi-fascist and anti-Semitic.

This is a worrying condition to be in for a pivotal regional state. Turkey is a NATO ally of long standing but, because of its reluctance to fight ISIS and Erdogan’s flirtation with Vladimir Putin, is no longer seen as a safe pair of hands. Talks on its accession to the EU have long been stalled—initially because of Franco-German prejudice against a Muslim majority country that damagingly validated Erdogan’s neo-Ottoman delusions—but it’s hard to see how this illiberal democracy can now become an EU member. Turkey is also currently head of the G20 group of advanced economies. It’s hosting a G20 summit this month in Antalya. Yet the AKP has twice hosted Khaled Meshaal, the Hamas leader, as the star turn at its annual congress.

Erdogan now has a choice. Emboldened by his election triumph, he may carry out his threat to extend the fight against the PKK to its US-backed Syrian Kurdish militia allies, if they take any more territory below Turkey’s southern border. That would complicate the US-led campaign against ISIS. It would also make the breach with Turkey’s Kurds irreparable. But he could also start talking to legitimately elected HDP members of the Ankara parliament, about the Kurdish minority’s legitimate demands for more political and cultural space. Vindicated by the vote, he could choose to be a statesman. The world will be watching.