Over the next decade, the Australian Government is planning to acquire seven MQ-4C Triton unmanned maritime surveillance aircraft, which will operate alongside between eight and 12 manned P-8A Poseidons. Together, they’ll replace the RAAF’s 18 AP-3C Orions. The high altitude and long endurance of the Triton are capabilities that manned platforms can’t match, and robots are good at carrying out boring tasks. These qualities make Triton a uniquely attractive platform for surveilling Australia’s vast maritime territories.

Australian interest in the Triton can be traced back to at least April 2001, when a Global Hawk completed a non-stop 23-hour flight from southern California to South Australia. But Australia’s commitment to the platform has been hot and cold—especially in earlier years— despite its clear value to the RAAF’s future needs. In order to understand why, it’s worth looking at the development history of Triton and its predecessor platform, the better-known Global Hawk.

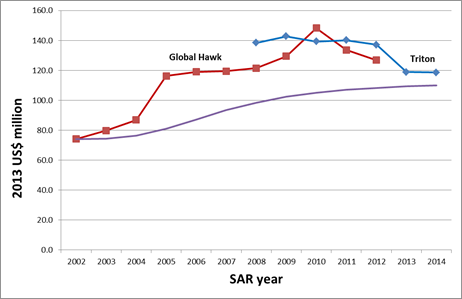

The histories of Global Hawk and Triton, presented in Figure 1, show the change in estimated unit procurement cost (excluding R&D) over the program life of both platforms. The curved line represents the average trend of cost estimates over the life of a developmental program, baselined to the 2002 estimate for Global Hawk costs. (The situation is actually a little worse than it looks here; Global Hawk development started prior to 2002 and earlier estimates were even lower.)

Figure 1: Predicted average unit procurement cost – Global Hawk and Triton

Source: GAO Assessments of Selected Weapons Programs 2004-2016 and ASPI analysis of data in Augustine’s Laws

Over the period 2002–2006 the estimated unit cost of Global Hawk increased by about 60%. US legislation requires that a development program be examined by Congress if costs exceed ‘25% of the current baseline or 50% of the original estimate’. As a result, the Global Hawk program was nearly cancelled by Congress in 2006. Instead, a restructure delayed planned increases to production rates and prioritised operational testing to iron out problems.

From 2005 to 2009, Global Hawk cost estimates were relatively consistent, and planned production remained steady at 54 aircraft. But in 2010, an increase in planned quantities of the Block 30 and relatively expensive Block 40 aircraft drove costs up again. The program was saved again in 2011 by Secretary of Defense Robert Gates, who certified the platform as ‘essential to national security’, but numbers suffered even so—in 2012 Global Hawk procurement was capped at 45 aircraft.

In 2006, Australia considered collaborating with the USN to develop the broad area maritime surveillance (BAMS) variant of Global Hawk that would later become Triton. But Australian collaboration was formally ruled out in 2009, after the Government decided to wait for a more mature platform. Given the history of Global Hawk, it’s easy to understand why.

But, as the graph above shows, cost estimates for the Triton have been much more consistent than Global Hawk. That’s likely due to more realistic baseline estimates USN had the advantage of starting with an airframe that had already been in development for a decade.

The first Triton was delivered to USN in 2012, after which estimated costs declined—perhaps reflecting dedicated efforts to rein in costs, as the USN’s planned quantity has remained steady at 70 units. Triton’s first flight took place in May 2013, and in February 2014 Prime Minister Tony Abbott announced that the Triton had been given first-pass approval to proceed to a more detailed evaluation.

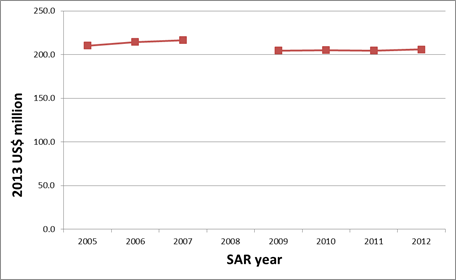

The other half of Project AIR 7000, the Poseidon, received first-pass approval in 2007. The development history of the Poseidon, as reflected in progressive cost estimates, is in stark contrast to the Global Hawk/Triton. The Poseidon is based on a Boeing 737 commercial airliner, with much of the production work occurring on the same assembly line. This has helped make it an extremely cost-effective and predictable acquisition. But it’s also in some ways less ground breaking than the Triton, and innovative capabilities carry significant higher development risks.

The corresponding Poseidon graph (figure 2) shows how remarkably consistent cost predictions have been.

Figure 2: Predicted average unit procurement cost – Poseidon

Source: GAO Assessments of Selected Weapons Programs 2007-2016 (2008 data point unavailable)

The 2016 Defence White Paper reaffirmed Australia’s plans to acquire seven Tritons for around A$3 billion. In the context of development costs, it’s easy to understand Australia’s earlier reservations about committing to the platform. Compared to the predictable development of the Poseidon, the Triton’s predecessor had a turbulent history. But the benefit of experience has given Triton a much more stable development. And, in the meantime, Global Hawk’s operating costs have been driven down repeatedly, which could translate into further benefits for the Triton.

Even with a recent setback in the form of flawed wing manufacturing, Triton appears to be well on its way to maturity. A shift from development phase to low rate initial production could be approved by October this year, and USN initial operational capability is scheduled for 2018. Australia’s acquisition of the aircraft should be pretty smooth.