Regular contributor Peter Layton drew my attention to the final chart in the ‘Tax Chartacular’ at the Mark the Graph blog. It shows Australia’s total taxation burden 1959–2011 as a proportion of the nominal GDP. It shows a steep decline in the total tax take over the past few years, suggesting that governments face some tough choice when setting spending priorities.

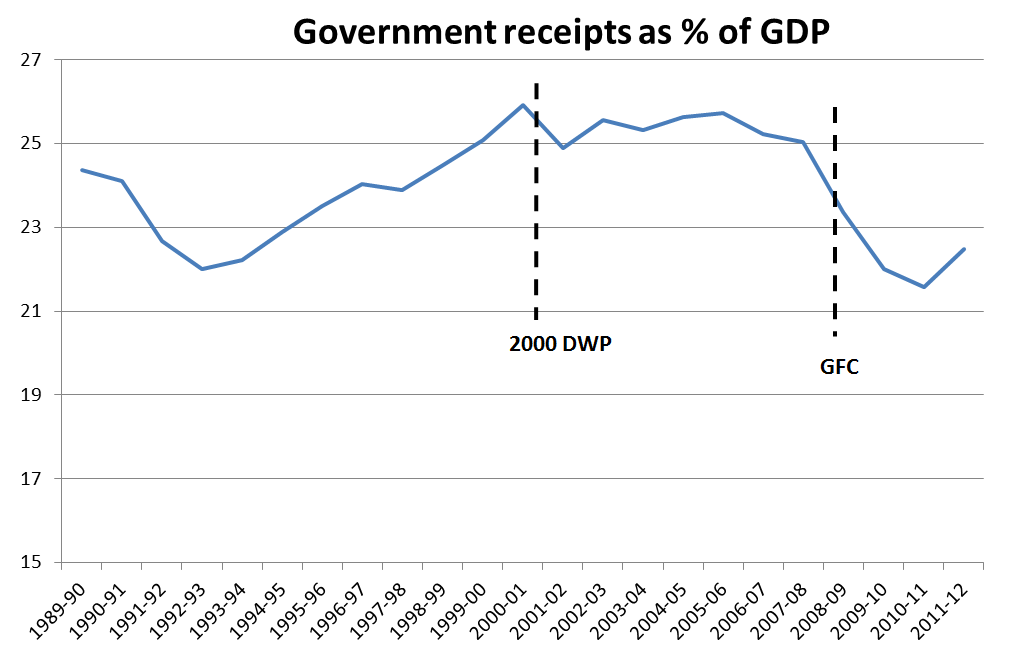

The data used to produce that chart was total taxation, which includes state revenues which aren’t available for defence. A better measure is to look at the total revenue received by the Federal Government (below, click to enlarge).

Sources: Australian Bureau of Statistics data set 5206 for GDP, budget 2012–13 for receipts.

Sources: Australian Bureau of Statistics data set 5206 for GDP, budget 2012–13 for receipts.

This graph shows very clearly the conundrum facing the government (and thus Defence) at the moment. During the period between the 2000 Defence white paper and the GFC in late 2008, Federal Government revenues averaged 25.4% of GDP. Since then the average has been 22.4%, a figure not seen since the first half of the 1990s.

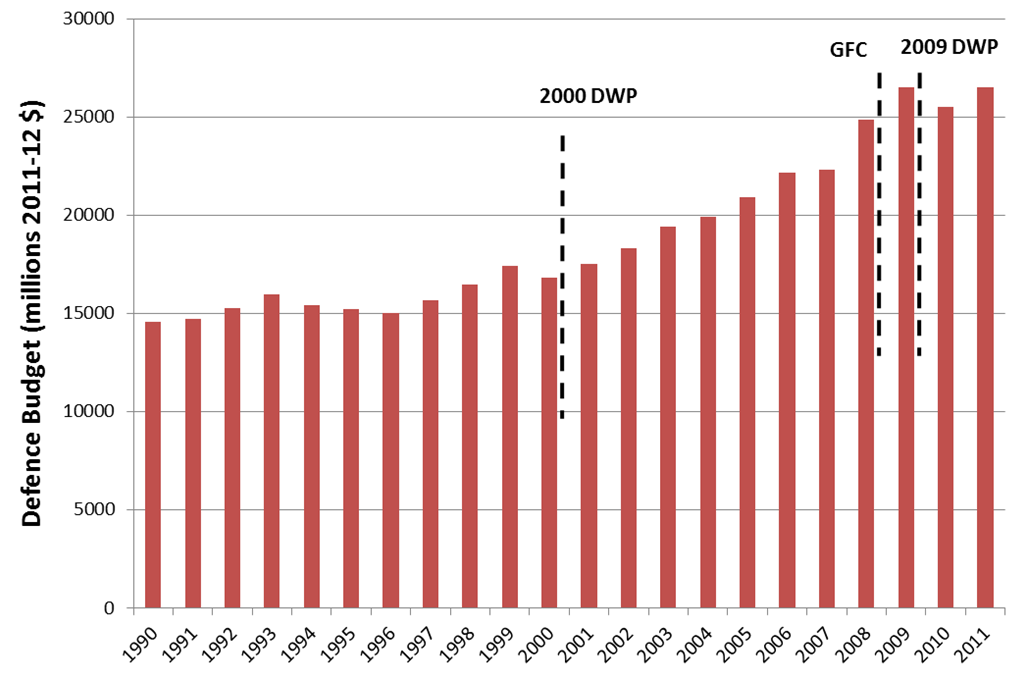

Here’s another chart, again drawn from ABS data. It’s the defence budget over the same period as the one above, with the effect of inflation removed.

Source: ASPI Cost of Defence brief 2011–12, based on ABS defence spending figures.

Source: ASPI Cost of Defence brief 2011–12, based on ABS defence spending figures.

As Mark Thomson pointed out in his 2010–11 Cost of Defence brief (p.106 ff.), the relatively flat period of the 1990s reflects the oft-seen impact of an economic downturn (the ‘recession we had to have’) and ensuing government stringency as it returns the budget to surplus. The ramping up of spending following the release of the 2000 Defence White Paper was enabled by the good fiscal position of the time—strong economic growth and high government revenues. Of course, it also reflects the relatively high priority afforded defence by the government at the time.

The 2009 Defence White Paper, on the other hand, was born at the wrong time. The spirit might have been willing, but the tax take was weak. So there should be no surprise that it fell over in just a few years.

Today it’s questionable whether either the priority or the funding is there for any substantial increase in defence spending. Both sides of politics have a long list of policy initiatives that will have to be funded from the revenues available to them in government in the future. Barring an increase in taxation or very strong economic growth, there’s going to be some furious lobbying for priority come budget time every year. If I had to bet, right now I think the ‘flat line’ of the 1990s might be more representative of the decade ahead than the ramp up of the past decade.

Andrew Davies is senior analyst for defence capability and executive editor of The Strategist at ASPI.