India has recently been called out for being the weakest link in the revitalised Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, a framework for cooperation involving three other democracies in the Indo-Pacific—Australia, Japan and the US. One of the reasons that’s been offered for India’s perceived reticence on the Quad is its ‘reset’ of relations with China after the tense military standoff between the two nations last year at the India–Bhutan–China border junction in Doklam.

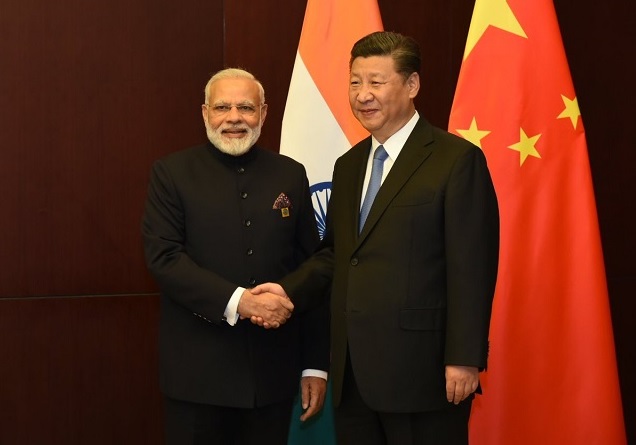

Given this, it’s worth asking whether the Wuhan summit between Xi Jinping and Narendra Modi, which formalised the ‘reset’ in April, was really a game-changer for India in the Indo-Pacific. The answer is ‘no’. The conciliatory change in New Delhi’s attitude to Beijing that started in February is nothing but tactical manoeuvring. India wants to maintain its strategic autonomy by hedging its bets on multiple partners.

It’s important to remember that the Modi government is counting down to the 2019 general elections and foreign policy is traditionally a non-issue at the ballots. New Delhi’s offer of an olive branch to Beijing in the form of the reset is essentially an attempt to buy temporary peace to avoid another Doklam-like confrontation. That theory is further supported by India’s denial of US claims that China has continued its activity on the Doklam plateau. The Modi government has also failed to put the proceedings of Wuhan on record, as is common practice.

China and India must overcome some other hurdles for any reset to be worth its name. The two nuclear-armed states share a long-running boundary dispute. Boundary transgressions by PLA troops are a routine feature, with regular skirmishes along the disputed ‘Line of Actual Control’. China’s all-weather friendship with Pakistan is another source of friction with India. New Delhi remains concerned about Beijing’s increasing encroachment on its strategic space, especially in the subcontinent and the Indian Ocean region, and is hiking foreign aid in response. China continues to make it difficult for India to join the Nuclear Suppliers’ Group and gain a permanent seat on the UN Security Council.

India has also deepened bilateral and trilateral defence and economic cooperation with the Quad nations in the past few months. The announcement of Australia’s exclusion from the Malabar naval exercises on the eve of the Wuhan summit appeared to be meant to please Beijing. But New Delhi has been consistent in its position on Australia’s participation in Malabar, denying it participation or observer status for many years, in keeping with its traditional emphasis on preserving its strategic autonomy. Maintaining the status quo on Malabar, given the attempt at a reset with China, seems logical from India’s point of view, even though some may have found it disappointing.

On the other hand, India’s bilateral naval drills with Australia, AUSINDEX, and its participation in Pitch Black 2018, the multi-nation air-defence exercise held in Darwin, are indications of New Delhi’s openness to deepening military ties with Canberra. India has continued its robust engagement in ‘2+2’ defence and foreign ministerial dialogues and trilateral security meetings with Japan and the US. India is reportedly close to signing a military communications agreement with the US, after years of negotiations, which would increase interoperability between the armed forces of the two countries. And New Delhi and Tokyo have agreed to conduct their first joint army exercises on counterterrorism later this year and are on the verge of signing a major logistics exchange and support agreement.

India has entered into bilateral and trilateral infrastructure development partnerships with the US and Japan in the form of the Asia–Africa Growth Corridor and the trilateral working group on infrastructure. It has also been steadfast in its opposition to China’s Belt and Road Initiative since last year, citing Beijing’s violation of territorial sovereignty norms and creation of unsustainable debt traps. Even though there were rumours of New Delhi softening its stance on the BRI earlier this year, in the context of the China reset, the Indian government has since reaffirmed its objection to the initiative. However, India’s decision not to get involved in the US–Japan–Australia infrastructure trilateral may be attributed to its failure to unlink the concept of the Quad from its anti-China connotation.

The first meeting of the rejuvenated Quad took place in Manila in November 2017, shortly after India emerged from the Doklam crisis. Since then, New Delhi has embarked on its China ‘reset’ to avoid another confrontation and returned to the holy grail of India’s foreign policy, maintaining strategic autonomy. India has also sought to engage with Russia, France and ASEAN, both to further its interests in the region and avoid confrontation in the run-up to an election.

It’s not clear yet whether India will end up embracing or rejecting the Quad. New Delhi seems unwilling so far to sign up to an arrangement with a larger agenda than a consultative forum. India’s emphasis on multi-alignment, outlined in Modi’s speech at the Shangri-la Dialogue, means that it will shun any initiative that has a pronounced anti-China rhetoric and tenor. At the same time, New Delhi will never cosy up to China because of the unresolved structural issues.

But that doesn’t mean that India has rejected the concept of the Indo-Pacific. India’s behaviour is consistent with its inclusive vision of the Indo-Pacific, in which it exercises strategic autonomy by emphasising a ‘non-bloc’ vision of security cooperation. The Quad’s future and India’s participation in it will depend on building an agenda that is compatible with New Delhi’s multipolar and non-bloc approach to the Indo-Pacific.