Peter Jennings’ piece ‘Indonesia and Australia: prisoner’s dilemma’ points out the main options in the shorter term for the Australian government in considering possible negotiations with Jakarta over Andrew Chan and Myuran Sukumaran’s urgent situation.

Peter Jennings’ piece ‘Indonesia and Australia: prisoner’s dilemma’ points out the main options in the shorter term for the Australian government in considering possible negotiations with Jakarta over Andrew Chan and Myuran Sukumaran’s urgent situation.

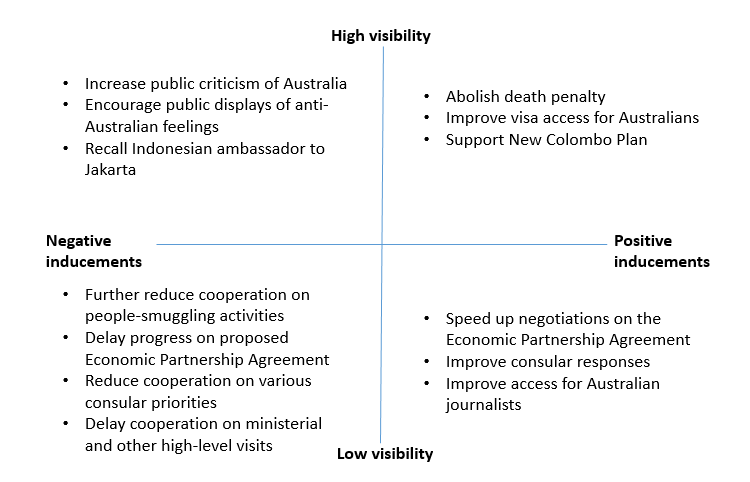

But since Indonesia is in a position to respond to any actions that Australia might take, it’s useful to consider what options are open to policymakers in Jakarta, presented in the following matrix (click to enlarge):

If President Jokowi were looking for ways to offer an olive branch to Australia, looking at the right hand side of the diagram, he could offer to take steps to abolish the death penalty, improve visa access for Australians to Indonesia (which has recently been relaxed for some other countries, but not for Australia) and—importantly—speed up negotiations on the Australia–Indonesia Economic Partnership Agreement. He could also—and looking beyond the looming Chan–Sukumaran case—support ways to improve Indonesian–Australian consular cooperation for other Australians who often face difficulties in Indonesia.

What Prime Minister Abbott must bear in mind, however, is that Indonesia has options on the left hand side of the diagram (‘negative inducements’) as well. The most immediately worrying of these are the high-visibility ones. It would be easy for President Jokowi to drop some pointed criticisms of Australia into the Indonesian media. In the excitable space that exists for public displays of emotion in Jakarta these days (demonstrations about all sorts of issues are almost daily occurrences in Jakarta), it wouldn’t be surprising if flag-waving students gathered together to support Jokowi on this issue. After all, Indonesians can be just as nationalistic as Australians.

Just as worrying in the longer term are the low-visibility responses that it would be easy for Indonesian policymakers to turn to. At any time, Australia is keen to build cooperation with Indonesia in various ways that are in Australia’s interests. Discussions about the proposed Australia–Indonesian Economic Partnership Agreement (AIEPA) seem to have proceeded quite slowly during the past 12 months. Slow progress during 2014 was perhaps not surprising given that the term of the previous administration under Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono was coming to an end. But it’s now important to resume negotiations over the AIEPA because Australia will not benefit if discussions are delayed. And almost every month, there are several high-level Australian teams of one kind or another (federal or state ministers, business groups, education teams, other professional groups, sporting and cultural organisations, media) looking for access in Jakarta. It would be easy for Indonesian policymakers to go slow on responding to Australian requests for meetings.

The prisoner’s dilemma matrix that Peter has presented is useful because it highlights the fact that at any time, Indonesia and Australia have many issues that need to be discussed. In choosing to up the ante in dealing with Indonesia over the difficult Chan–Sukumaran dilemma, Australian policymakers need to bear in mind that Jakarta’s got a few cards to play as well.

Peter McCawley is a visiting fellow with the Indonesian Project in the Crawford School, Australian National University. Image courtesy of Flickr user jmiller291.