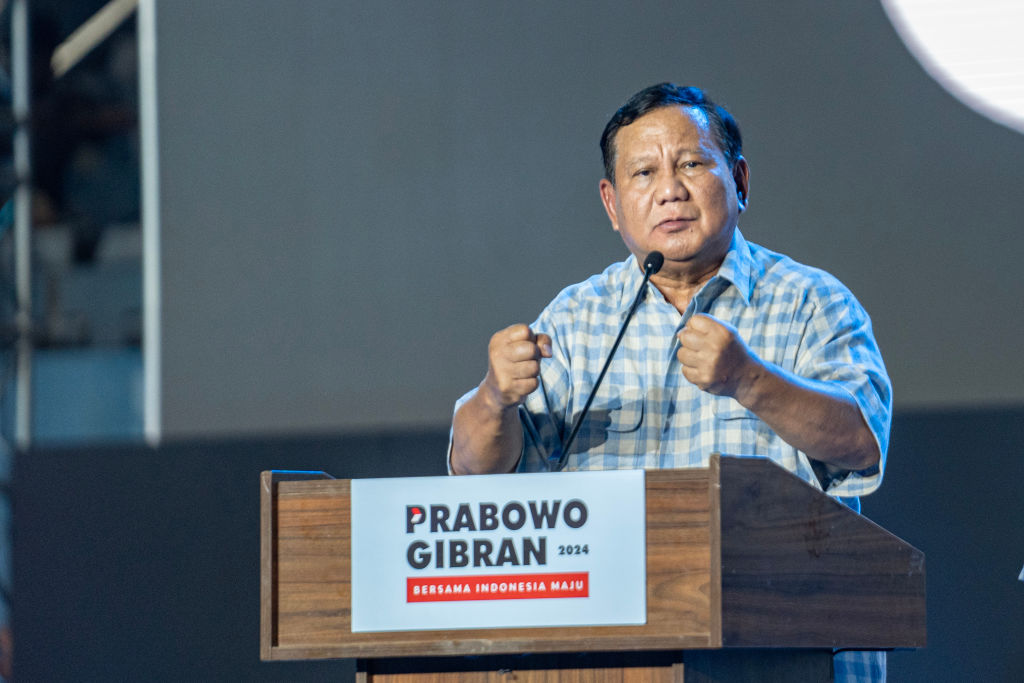

With Indonesian President Joko (Jokowi) Widodo fast approaching the end of his 10-year term and the February election result now official, it’s time to consider how incoming president Prabowo Subianto will shape the country’s strategic and defence affairs. While the country’s overall strategic outlook is unlikely to shift, there are some changes the new president and new defence minister could—and should—make.

First and foremost, as current defence minister, Prabowo will continue to oversee the much-needed military modernisation program, which aims to strengthen the country’s maritime defences by upgrading the navy and air force. It has been Prabowo’s priority and was one of his election promises.

But there is a lack of coherence in Prabowo’s approach that is problematic. The program, which promises fighter jets, submarines and patrol boats, had in 2023 only met 51 percent of its targets for the air force, and 60 percent and 76 percent for the army and navy, respectively. His flurry of travel as defence minister from 2019 yielded the signing of contracts for acquisitions from the US, France, Turkey, South Korea and Britain, as well as deeper overall defence ties. Yet, as the ill-fated attempt to acquire second-hand Mirage 2000 fighters from Qatar attests, it is unclear whether these purchases from multiple suppliers will further strengthen Indonesia’s defence posture or fragment it.

Additionally, questions remain whether these big-ticket items are appropriate for service requirements or simply provide opportunities for sectioning off parts of the national budget.

The new Prabowo administration must also address the inevitable tension between the need to invest in maritime defence and the ongoing primacy of the army. Of Indonesia’s contemporary security challenges, several are land-based and pressing: the army is still heavily relied upon for disaster relief and food security and is tasked with maintaining a sprawling territorial presence. The military must balance deterring potential threats from a larger adversary and attending to internal emergencies facing 280 million citizens on land. Effective deterrence in the region is critical, given China’s shameless bullying of Indonesia’s partners, such as the Philippines, in the South China Sea.

Such efforts would be considerably aided by the publication of a new defence white paper or strategic update. The last such document, the 2015 white paper, was issued nearly a decade ago. An update would shift Indonesia’s strategic thinking away from threats such as communism and total people’s defence and help articulate the nation’s own ideas of deterrence.

A new strategic document would also allow Indonesia, as Southeast Asia’s largest state and a key Indo-Pacific player, to lead its regional neighbours by example. This is critical given the contemporary security landscape marked by wars threatening food security, sharpened US–China strategic competition, tensions in the South China Sea and climate change pressures.

Lastly, such a document would help outline a new phase of military modernisation and detail the government’s response to grey zone threats, particularly in the cyber realm. It should also provide transparency about how the national budget would be spent.

And yet we’re unlikely to see any shifts in prevailing strategic thought anytime soon.

Unlike his predecessor Jokowi, Prabowo has a personal interest in the defence portfolio and will appoint loyalists to defence and security roles to protect his legacies. An unofficial mock-up of the cabinet floated on social media shortly after the election pictured retired Lieutenant General Sjafrie Sjamsoeddin, Prabowo’s confidante and classmate in the special forces (Kopassus) as defence minister, and retired Lieutenant General Muhammad Herindra, also from Kopassus, staying on as deputy defence minister. That‘s probably not far off what will happen.

Prabowo and his ex-Kopassus coterie hold the realist’s world view that might equals right. Prabowo has even written a book on how Indonesia’s military must assiduously protect the country’s natural resource wealth from foreign actors. His deputy Herindra said in an interview last year that ‘the world is anarchistic, chaotic. If we are weak, we will be eaten. It is not about Indonesia not having a power projection; we just want to defend our nation’s sovereignty.’

As for other key positions, such as the military and police chiefs, Prabowo will inherit Jokowi appointees who will serve out their terms for the first few years. They are considered loyal to Jokowi’s interests but often also have links to Prabowo. For example, while the current army chief of ataff, General Maruli Simanjuntak, is the son-in-law of Jokowi’s senior minister and adviser Luhut Binsar Panjaitan. Luhut reportedly has good relations with Prabowo through their shared background in Kopassus.

For partners like Australia, Prabowo as defence minister has helped ensure that Indonesia is a good neighbour. Under his watch, defence cooperation has deepened, with Indonesian military cadets graduating for the first time from Australian Royal Military College, Duntroon. Prabowo has also maintained good relations with Australia’s key ally, the United States, meeting several times with Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin and overseeing the return of Indonesian cadets to American military academies.

But Indonesia’s military needs investment and support in developing scenario-based planning and joint operations. These are areas in which Australia, the US and other partners can make valuable long-term contributions.

As president, Prabowo will want Indonesia to remain a good neighbour to Australia and, notwithstanding unforeseen events provoking pushback from the Australian public or inciting Prabowo’s nationalist sentiments, he should have every chance of success. To achieve regional stability in the prevailing strategic environment, everybody needs good neighbours.