Australian Defence white papers have long identified the strategic import of ‘a secure South Pacific and Timor-Leste’. As renowned strategic thinker T.B. Millar once reflected, Papua New Guinea is an ‘an exposed and vulnerable front door’, as if it was in ‘hostile hands’ it would ‘make attacks on our east coast much easier—Port Moresby, after all, is closer to Sydney than Darwin is’.

Australian Defence white papers have long identified the strategic import of ‘a secure South Pacific and Timor-Leste’. As renowned strategic thinker T.B. Millar once reflected, Papua New Guinea is an ‘an exposed and vulnerable front door’, as if it was in ‘hostile hands’ it would ‘make attacks on our east coast much easier—Port Moresby, after all, is closer to Sydney than Darwin is’.

Australia is Papua New Guinea’s largest aid and military donor (primarily via the Defence Cooperation Program and the Pacific Patrol Boat program), and trade and investment partner. Australia also effectively gave PNG a security guarantee under the 1987 Joint Declaration of Principles, as reaffirmed in the 2000 Defence White Paper (PDF). Consequently, Australia has been able to exercise considerable influence over Papua New Guinea for much of the period since its independence.

This situation is changing. Papua New Guinea now has new opportunities which are eroding Australia’s influence.

First, changes to the broader Asia-Pacific power structure have generated geopolitical opportunities. The ‘rise’ of China has motivated the United States to ‘pivot’ or ‘rebalance’ to the Asia-Pacific. While there is only a minimal risk that China and the United States will engage in zero-sum competition for military influence, both powers have engaged more extensively with Papua New Guinea in the diplomatic, aid and economic realms. Japan, Malaysia, Korea, Indonesia, Iran, Cuba, Russia and the United Arab Emirates are also becoming involved as aid donors and diplomatic partners. As Papua New Guinea has more choice of external partners, it no longer necessarily needs to identify itself as falling within an uncontested Australia and New Zealand sphere of influence.

Second, that increased choice has opened up regional opportunities. Since 1971, the dominant regional political institution has been the Pacific Islands Forum (PIF), comprising all independent regional states, along with Australia and New Zealand. Empowered by their greater choice of partners and encouraged by an emboldened Fiji, Papua New Guinea and other regional states are creating, or strengthening, alternative regional and sub-regional institutions and organisations such as the Melanesian Spearhead Group and Pacific Islands Development Forum that exclude Australia, New Zealand and other traditional partners.

Papua New Guinea is also a member of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC), and is seeking full membership of the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN), of which it currently has observer status. Papua New Guinea, along with Fiji and Vanuatu, has also joined the Non-Aligned Movement. Fiji has encouraged South Pacific states to form an alternative caucus grouping at the United Nations, the ‘Pacific Small Island Developing States’ (PSIDS) group, which has effectively replaced the PIF in this role.

Papua New Guinea’s growing confidence has been enhanced by its economic opportunities. Its Southern Highlands are home to the massive Exxon-Mobil LNG project, which it is predicted will generate total revenue for the government of about US$31bn to 2040. It also receives revenue from several other natural resource projects, including the $1.5bn Ramu nickel mine, in which Chinese companies have invested, and has the potential for deep-sea mining.

As a result of its opportunities, Papua New Guinea is less likely to be susceptible to Australian influence in the future.

The most notable recent example of Australia’s declining influence are the circumstances surrounding the arrangements to process and resettle asylum seekers in Papua New Guinea. These arrangements have their antecedents in the 2001 ‘Pacific Solution’, which introduced processing of asylum seekers in Papua New Guinea and Nauru (it ended in 2008). In exchange, Australia made no additional development assistance payments to Papua New Guinea.

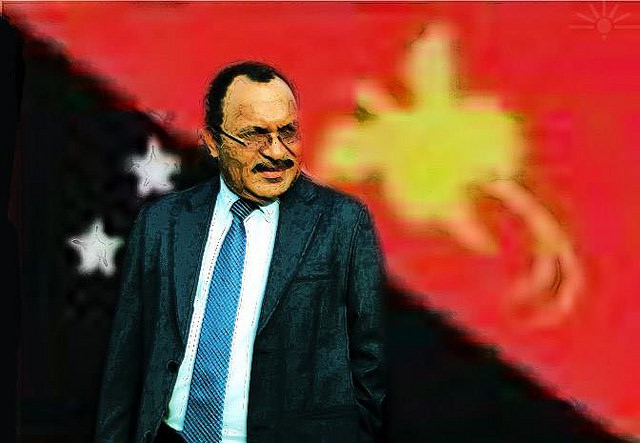

In contrast, under the 2013 arrangements, Papua New Guinea Prime Minister Peter O’Neill demanded—and received—a total re-alignment of Australia’s aid program to support his government’s priorities. Australia has agreed to provide an extra $420m of development assistance, on top of the projected $507.2m in assistance budgeted for Papua New Guinea in 2013–14.

Moreover, when the arrangement was agreed, then Prime Minister Kevin Rudd indicated his understanding that most refugees would be resettled in Papua New Guinea. This belief was shared by Tony Abbott. In March 2014, O’Neill contradicted both Rudd and Abbott by announcing that Papua New Guinea will only resettle ‘some’ people whose claims are recognised. While O’Neill recanted that statement in April 2014, the fact that he felt empowered to openly contradict two Australian prime ministers suggests a growing degree of confidence in Papua New Guinea’s attitude to Australia.

Australia may find itself with less influence over its relationship with Papua New Guinea in the future, which will have important strategic implications. Unfortunately, it’s not yet clear that the Australian government has come to this realisation.

Joanne Wallis is a lecturer in the Strategic and Defence Studies Centre at the Australian National University, where she also convenes the Asia-Pacific Security program. The journal article on which this post is based was recently published in Security Challenges and is available here. Image courtesy of Flickr user Global Panorama.