Most of the commentaries about Henry Kissinger’s life seem to agree that his greatest achievement by far was the breakthrough in 1972 in America’s relations with communist China. That event was certainly an outstanding geopolitical victory for Kissinger’s view that what really mattered in the world was the stability of great power relations.

However, I believe the more important breakthrough was the negotiation of agreed strategic nuclear force levels with the Soviet Union. Kissinger observed that his greatest challenge as America’s secretary of state was the avoidance of nuclear war with the USSR.

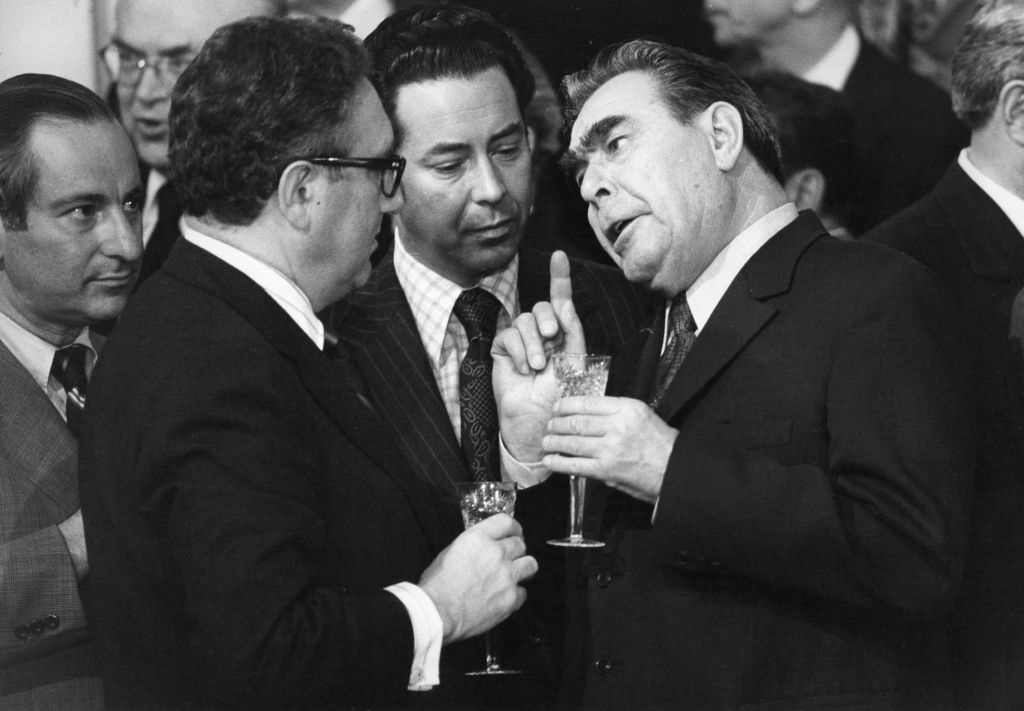

We now forget just how dangerous the strategic nuclear arms race between the US and the Soviet Union was throughout the 1970s and 1980s. Those of us who worked then as senior intelligence officials were very aware of the ever-present danger of nuclear war erupting with little or no warning. On 26 May 1972, President Richard Nixon and General Secretary of the Soviet Communist Party Leonid Brezhnev signed the Antiballistic Missile Treaty (ABM Treaty) and the interim Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty (SALT I Treaty), which for the first time during the Cold War committed the US and the USSR to agreed limits on the number of strategic nuclear warheads and missiles.

By comparison, in 1972 China was at most a second-rate power with only poorly developed nuclear capabilities, which left it vulnerable to a total disarming nuclear strike by either the Soviet Union or the US. And we know that the USSR did seriously consider using nuclear weapons against China in 1969.

On the American side, high-level military and civilian experts were engaged in prolonged and detailed discussions with the USSR about the locations and numbers of Soviet intercontinental ballistic missiles, submarine launched ballistic missiles, and warheads carried by strategic nuclear bombers. The Americans soon learned that their opposite Soviet military experts were not comfortable discussing these highly classified and tightly held Russian secrets in front of their own civilians!

The 1972 ABM Treaty permitted each side the antiballistic missile defence of their capital city, as well as one separate group of ICBM silos. This treaty lasted for 30 years throughout the Cold War until the US withdrew from it in June 2002. Russia responded by likewise withdrawing from this Treaty.

SALT I was succeeded by SALT II, provisionally signed in 1979. These treaties imposed agreed limits on strategic nuclear warheads and missile launchers. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, there was agreement on further and more drastic cuts to the numbers of strategic nuclear weapons by each side. This resulted in the New Start Agreement of 2010 which limited the number of strategic nuclear warheads on each side to between 1500 and 1,675. According to the International Institute for Strategic Studies, this compared to actual numbers at the time of SALT I of 14,530 for the US and 12,403 for the USSR. These were indeed historic cuts, but they also got the two sides talking more widely about the dangers of nuclear war and so arguably reduced the probability of nuclear conflict, not just the consequences of war if one nevertheless happened.

Russia has recently suspended its commitment to the New Start Agreement but says it’s still abiding by the numerical ceilings agreed to. The Russians claim their ‘suspension’ was in retaliation for America’s withdrawal from the Intermediate Nuclear Forces (INF) agreement in October 2018 because of Russian non-compliance. The INF agreement had banned all theatre nuclear weapons with ranges from 500km to 5500 km and resulted in the destruction of almost 2700 short and medium range theatre nuclear weapons in Russia and Europe.

Although Kissinger was instrumental in beginning this remarkable process of agreeing on numbers, locations, and reductions of nuclear weapons between the US and the Soviet Union we are now, for the first time since the end of the Cold War, seeing a complete breakdown in any further negotiations. And both sides seem set on building a new round of more accurate nuclear missiles together with highly accurate conventional weapons capable of striking nuclear weapons sites. Moreover, confidence-building measures and high-level on-site inspections now seem to be in complete abeyance. Russia and America are not talking to each other at a time when tensions between these nuclear superpowers are at a post–Cold War high.

When I was last in Moscow, in June 2016, former General of the Army Vyacheslav Trubnikov and Sergei Rogov, who was a Cold War arms control specialist, belligerently threatened my delegation that: ‘America and Russia are not talking to each other at all these days and, as tensions are at an all-time high, you Australians need to understand that in the event of nuclear war between Russia and America missiles will fly in every direction.’ They both went on to specifically threaten Pine Gap.

This brings me to Kissinger’s appreciation of the crucial role Pine Gap played in reassuring Washington about Soviet compliance with the detailed counting rules of the various strategic arms limitation agreements throughout the 1970s and 1980s. The working knowledge I have of this was from Corley Wonus who was the CIA Station Chief in Canberra in the late 1970s when I was head of the National Assessments Staff working for the National Intelligence Committee. He was the senior American intelligence officer in Australia in charge of running Pine Gap. Wonus was the first CIA station chief from the science and technology side of CIA, as distinct from the ‘spooks’ component. He had been instrumental in designing the Rhyolite satellite which, from geostationary orbit of 32,000 kilometres, sent the intelligence collection signals down to Pine Gap. For his part in designing one of the world’s most powerful intelligence collection facilities, Wonus was awarded the Distinguished Intelligence Medal, which is CIA’s highest award.

In 1978, Wonus told me that Kissinger had been outraged by Prime Minister Gough Whitlam’s revelation in 1972 that Pine Gap was an important CIA ‘spy base’. Its public cover until then had been merely as a ‘Joint Defence Space Research Facility’. Kissinger had demanded that CIA advise him whether Pine Gap could be closed and relocated elsewhere in the world. Wonus confided in me that he had firmly told Kissinger that with then foreseeable technology Pine Gap was irreplaceable.

This was because the signals from the satellite were so tiny that the collection facility had to be surrounded by a huge area that was electromagnetically almost completely silent. Pine Gap was one of very few locations in the world that had such critical characteristics. Moreover, Pine Gap’s satellite operations centre was very well positioned to manage the physical task of ‘re-bore sighting’ (retargeting) of the Rhyolite satellite on new Soviet military intelligence targets. This demanding operational task was enhanced because the Siberian landmass, where most Soviet operational nuclear missiles were located, was directly to the north of Pine Gap.

In addition, the location of Pine Gap had to be free from the threat of interception on the ground. This was because the downlink signals were unencoded at that time. Encoding them, I was told, would have made these tiny signals even more difficult to receive. Wonus reassured Kissinger that ASIO would continue to prohibit any members of the Soviet embassy from visiting Alice Springs.

So, that’s how Pine Gap was saved from Kissinger’s interest in retaliation for the Whitlam government’s exposure of one of America’s most important intelligence-collection facilities in the Cold War. In 1987, we acknowledged publicly for the first time in a defence white paper that Pine Gap, and the base at Nurrungar near Woomera, contributed vitally ‘to verification of arms limitations measures of the United States and the Soviet Union, and to timely United States and Australian knowledge of developments that have military significance—including early warning of ballistic missile attack on the United States or its allies’.

In the final analysis, as Richard Haass has observed, Kissinger’s priority of avoiding nuclear war with the Soviet Union encouraged nuclear arms control talks, rules of the road for managing conflict, and regular summitry—all of which helped keep the Cold War cold when it could have turned hot or, worse, led to nuclear escalation. And Pine Gap played a critical role in reassuring the Americans.

In his 1979 memoir, The White House years, Kissinger wrote that he believed the SALT agreements ‘could begin the process of mutual restraint without which mankind would sooner or later face Armageddon’.