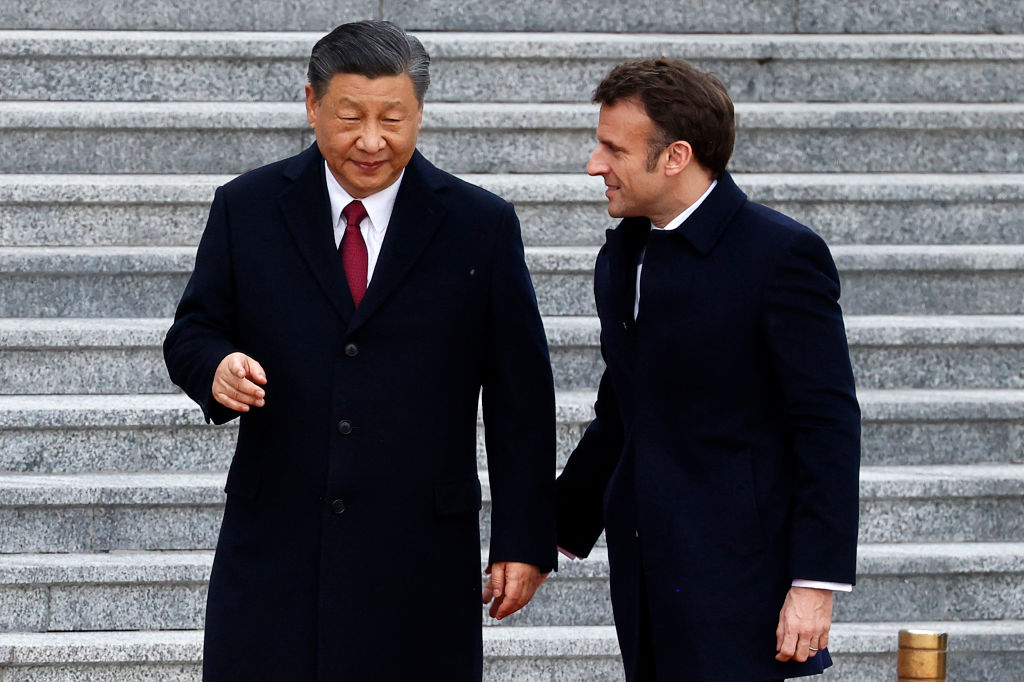

French President Emmanuel Macron’s recent visit to China and his subsequent comment that Europe should not get dragged into a confrontation over Taiwan made clear that his vision of strategic autonomy involves concentrating on security in Europe while pursuing financial prosperity through Beijing.

This betrays a continuing fantasy that security and economics can be treated separately. Macron’s attitude will reinforce a view spreading in the US that America’s interests are best served by focusing less on Europe and more on the Indo-Pacific region.

This episode has served as an unpalatable reminder that for all the rhetoric about democracies standing together against powerful authoritarians wherever they are in the world, some Western leaders remain ready to retreat to narrower and shorter-term definitions of their national interests.

This is entirely the wrong instinct. What is needed to constrain increasing collaboration between Moscow and Beijing is a form of grand strategic cooperation in which Europe, the US and others work together from the Atlantic to the Indo-Pacific.

The risk for Macron, given the precarious state of strategic preparedness in many traditional European powers, is that the US will hold him to account. The implication that tensions outside Europe are not Europe’s to help manage will fuel complaints already simmering in the US that it is doing more than its fair share of confronting the Russian menace on NATO’s doorstep and that its interests are perhaps better served focusing on the Indo-Pacific region.

If recriminations over the sharing of responsibility for Ukraine were to lead to dwindling global support, it could force Kyiv into negotiating with Russian President Vladimir Putin from a weak position, likely resulting in the cession of territory.

This would reward his blatant aggression and deliver a devastating blow not just to Ukraine, but also to Western unity, the perceived strength of liberal ideas and the West’s deterrence strategies that provide the best hope to de-escalate the war and prevent future conflicts.

This is what Putin wants, of course. It is also what Beijing wants to—and thinks will—happen. It is, in part, why Chinese leader Xi Jinping formed his ‘no limits’ partnership with Putin and why Beijing is helping Russia.

Beijing’s confidence stems from Xi’s view that democracies are structurally weak and lack the stamina to outlast authoritarian regimes, which are more focused on long-term objectives and willing to see their people suffer for a political cause.

It is doubtful whether Xi understands democratic societies as well as he thinks he does, but principles such as supporting Ukraine cannot be taken for granted.

Ukraine skeptics in the US are split between the ‘America firsters,’ who ignore history and reality to argue that domestic needs can be solved with isolation, and security advocates who judge that Beijing is the more important long-term challenge and therefore should be the focus of limited US resources.

Increased US concentration on Beijing might appeal to many in the Indo-Pacific region. But reduced US support for Ukraine — whatever the motive — would embolden Beijing and confirm Xi’s theory that the democratic world is in decline. This would harm the West’s ability to deter aggression globally and increase the risk of future conflicts.

Fortunately, there is an alternative: collective grand strategic thinking through better use of partnerships. It is the same logic that has produced AUKUS and the revitalization of the Quad. The US should focus on Beijing but cannot do so by leaving Ukraine to the predations of Moscow.

Europe, specifically Germany and France, must therefore step up. The fact is, the EU collectively can take on Russia in a way that no grouping in the Indo-Pacific region can do to counter Beijing’s power.

All countries want to be able to make independent decisions to advance their interests. But there is a distinction to be made between sovereignty and autonomy. Sovereignty does not always mean making decisions alone but can involve drawing strength from partnerships with others who share core values and interests and using the space created to make decisions based on long-term priorities.

NATO as a whole understands this, as do senior members of the EU Parliament and European Commission, including Commission President Ursula Von der Leyen and legislator Reinhard Butikofer.

Many small EU nations get it as well, as reflected in Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania being among the largest providers of bilateral aid to Ukraine as a share of national gross domestic product. Germany’s Greens, part of the country’s ruling coalition, get it too, particularly Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock, among the strongest appreciators of the connection between individual human rights and security.

Macron’s Beijing trip is unlikely to change this picture. But the implication that Macron and others do not see stability and security in the Indo-Pacific as a concern will have an impact on deterrence in the region and will amplify concerns in the US about major European powers’ commitment.

Chinese state media are already encouraging other countries to follow Macron, with China Daily saying he has ‘showed the rest of the world … it is possible to reject bloc confrontation and adhere to an independent policy.’

The US, NATO and the EU should answer with a combined show of resilience in supporting Ukraine against Russia — and delivering a clear message that this effort would be matched in the Indo-Pacific.

Global authoritarianism, as we are seeing through the behaviour of Beijing and Moscow, is being aggressively pushed as an alternative to democracy in a bid to upend the global order and to advantage might over right.

To confront and deter this push, liberal democracies need to move beyond talking about the connectedness of security in the Pacific and Atlantic regions and act on it. Stability, security and prosperity require working together and harnessing our strengths. By all means, this cooperation should recognize unique regional needs, leadership and contributions, but it should sit under a collective strategy.

This means Europe stepping up considerably to confront the autocrat on its eastern doorstep, with continuing support from the US and Indo-Pacific partners. It also means Europe recognizing that authoritarianism on its doorstep cannot be separated from authoritarianism in the Indo-Pacific.

The growing pressure and confidence of authoritarian regimes must be checked. It is disappointing that even as we see Russian atrocities in Ukraine and Beijing’s targeted aggression and coercion, some political leaders think they can split Moscow and Beijing.

They cannot be split. They are two parts of the same problem.