It might sound odd, but interstate behaviour turns out to be something that can be understood by modelling it as a complex system. Our modelling of interstate interactions over a very long timeframe seems to be robust enough to show the patterns of decline and fall of states. As an example, it’s solid enough to model the post–World War II period of prosperity and growth—and show the dominance of the US along with the rise of other powers we have experienced.

Looking ahead, it even seems able to indicate some important attributes that the interstate system might have as a result of the direction in which President Donald Trump is taking the United States.

A disturbing but not particularly surprising insight from the modelling is that Trump’s ‘America First’ agenda may well result in the US being the strongest nation—but mainly by creating a poorer and less capable future world—one where all nations lose, but other nations lose more than the US does. In other words, it’s not a ‘win–win’ world where all prosper, but a more selfish, narrower world.

Whether he realises it or not, Trump is trading off national wealth for global power. That’s because his isolationist policies seek to create events that are qualitatively different from the great run of historical events.

Those events—world wars, depressions, even the collapse of the Soviet Union—are, from a complex systems perspective, merely the working though of perturbations to the global system, the ensemble of competing and cooperating nation-states. Broadly, the system absorbs these perturbations over a relatively short period of time and returns to its trajectory.

But Trump seeks, instead, to reset the fundamental parameters of the world order rather than merely perturb them—and that will have consequences for the world’s balance of power.

We’ve modelled the ensemble of nation-states as a complex system, allowing us to examine the emergence and evolution of both wealth and power under different conditions of cooperation and competition. These models can be tuned for the different domains—such as land, sea, air, space and cyberspace—in which states interact. And, like all models of complex systems, they don’t purport to show precise behaviour, but rather the general classes of behaviour of the system—in this case, the classes of behaviour reachable by a system of real states that cooperate and compete with each other.

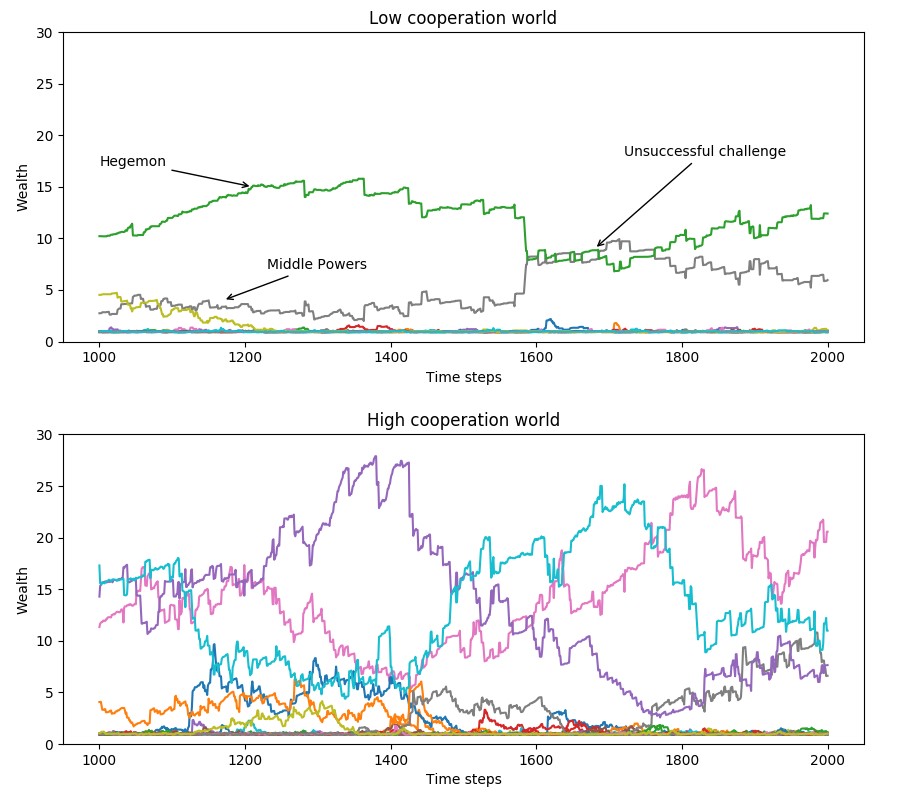

The graphs below shows some of our results with the model tuned for the physical domains, rather than the cyber domain. In these traditional domains, cooperation is manifested as trade in physical goods, and competition, in the limit, is manifested as kinetic warfare. We can see how the wealth (and hence power) of an interacting suite of initially equal states rises and falls over time for different levels of cooperation and competition. The upper graph shows a world where international competition rather than cooperation is the norm—a world not unlike that which existed in the lead-up to World War II. The lower graph shows a world with a bias to cooperation—not unlike the post-war world.

Changes in the wealth of states that emerge over time for model runs with two different levels of cooperation

| Notes: There are 20 initially equal interacting states in each case, and the graphs show the evolution of wealth (measured in arbitrary units) from time step 1000 to time step 2000. (Note that these are time steps in the model, not historical years.) A model run takes about 1000 steps to settle down, after which the behaviour doesn’t change, even beyond 100,000 steps. The upper graph shows the dynamics for low levels of cooperation. This shows the emergence of a long-lived hegemon, a few middle powers that occasionally, and usually unsuccessfully, challenge the hegemon, and a bunch of weak powers that struggle at very low levels of wealth. The lower graph shows the dynamics for higher levels of cooperation. Hegemons emerge but don’t last as long, being periodically challenged and replaced. There are more middle powers and they are more assertive, and even the weakest powers rise in wealth. The overall wealth in this ensemble of states is much greater than that in the upper graph, and the hegemons themselves, while they last, are much wealthier. Source: Adapted from Figure 3 of Dmitry Brizhinev, Nathan Ryan and Roger Bradbury, ‘Modelling hegemonic power transition in cyberspace’, Complexity, 2018. |

In the competitive world of the upper graph, a persistent structure to the international order emerges spontaneously. The structure consists of a long-lived hegemon of vast wealth, a relatively few middle powers whose wealth (or power) together don’t rise to the level of the hegemon and whose longevity is conspicuously less than the hegemon’s, and a tail of small, weak and relatively short-lived powers.

In earlier times, we saw these structures arise regionally, the Roman Empire being a case in point. But in more recent times the structure has become global, and today’s hegemon is, obviously, the US.

In the model, as in the real world, competitive challenges to the hegemon from rising powers are more often than not rebuffed, as can be seen at about time step 1600 in the competitive world of the upper graph in the figure. Thucydides’ Trap is a risky place for the challenger, as history shows. But such challenges are more likely to succeed in the cooperative world of the lower graph, as can be seen at about time steps 1500 and 1750. However, while these are successful transitions, the challengers don’t upset the system, but merely take the hegemon’s place in the same overall structure.

The two graphs capture the essence of the US’s strategic choices. In the aftermath of World War II, the US, the world hegemon, reset the international balance distinctly towards cooperation through the Bretton Woods agreement. It created a world with a bias towards international cooperation that ushered in 70 years of economic growth.

The Bretton Woods reset corresponds in the model to pushing the ensemble of nation-states from low levels of cooperation to higher levels—that is, from the system in the upper graph to the system in the lower graph. When that happens, global wealth rises, but with it more states rise in wealth, creating a significant number of wealthy middle powers (where before there had been few).

After Bretton Woods, the US rode on the top of the rising tide and remained the hegemon throughout the creation of what we now call ‘the rules-based international order’. But that allowed the emergence over time of a group of rising powers that could potentially challenge its hegemony, including Japan, the EU and, of course, China. That reset greatly advantaged the US, allowing it to grow richer and more powerful than it otherwise would have. But it also created a pool of possible challengers to its hegemony, and so created the catalyst for Trump’s reset—‘America First’.

There’s a certain logic in Trump’s agenda, even if it is not witting. It seeks to undo Bretton Woods and push the world’s ensemble of nation-states back to the low levels of cooperation seen in the upper graph.

This reset would have several distinct effects. First, all states, including the hegemon, would be poorer than they otherwise would have been. But the reset would have a second, more subtle effect. It would disproportionally impoverish the middle powers immediately below the hegemon in the pecking order, as can be seen in the upper graph. Thus, it would make it harder for other powers to rise and challenge the hegemon, extending the duration of US hegemony.

Can Trump’s perverse logic of narrow self-interest really be seen as a grand strategy? Or has he merely stumbled upon a policy setting that has vast strategic consequences? We may never know, but we will certainly experience the consequences.