Nuclear arms control has always involved two separate efforts: designing arsenals to ensure they are threatening but not destabilising; and enunciating declaratory policy to clarify expectations about when and why nuclear weapons might be used. The second of those efforts involves both positive security assurances (provided by nuclear weapon states to allies and partners), and negative security assurances (provided by nuclear weapon states to non-nuclear weapon states and potential adversaries). A pledge not to use nuclear weapons first during a conflict, for example, is one variety of negative security assurance. During the Cold War, the Soviet Union made such a pledge but NATO, fearing forward-deployed Soviet armour, did not. For the US to provide such a no-first-use commitment to its adversaries might well have weakened the assurances it provided to its European allies.

The Soviet pledge was never entirely credible—Moscow certainly had an interest in early nuclear use in naval contests, where it was conventionally weaker—and Russia withdrew it in the early 1990s. But over recent years, the notion of ‘no first use’ has started to make a comeback—albeit disguised as a declaration about ‘sole purpose’. What, you may ask, is a sole purpose declaration? It’s a declaration that nuclear weapons states make to the effect that ‘the sole purpose of the possession of nuclear weapons is to deter the use of such weapons against one’s own state and that of one’s allies’.

When the Evans-Kawaguchi International Commission on Nuclear Nonproliferation and Disarmament made its final report, it gave an enthusiastic endorsement to the notion of ‘sole purpose’ declarations. When the Commission explains the attractions of such a declaration, it’s perfectly honest about what those are: a sole-purpose declaration is essentially a no-first-use commitment disguised under a different formulation (see paragraph 17.28 of the Final Report). Indeed, read strictly, a sole-purpose declaration might be interpreted as an even more severe restriction than a no-first-use commitment, because if the purpose is solely to ‘deter’, there’s not necessarily a recognition of the entitlement to retaliatory second use. If deterrence fails, nuclear weapons have failed in their sole purpose.

For its proponents, the attractions of a sole-purpose declaration lie precisely in its ability to reduce the mission of nuclear weapons and thereby the likelihood of use. In principle, it makes disarmament more achievable, because all nuclear weapons are strategically related only to each other. But doesn’t a sole-purpose declaration trip over precisely the same hurdle that made a no-first-use pledge sound incredible? Would a nuclear-armed state facing conventional defeat actually abide by the pledge? Many states build nuclear weapons because of security worries—including a worry about the prospect of conventional defeat.

At a deeper level, why would we want to corral nuclear weapons into an artificial, strategically-separate world within which they deter only each other? Why should nuclear weapons deter nuclear use, but not anything else—not great power war, not major conventional attack, not use of chemical or biological weapons, not dangerous contests in escalation. In reality, nuclear weapons have a wider rather than a narrower role. They help set ceilings on conflict wherever conventional imbalances exist—and those either already do exist, or potentially might exist, across a wide range of possible conflicts. Even a conventionally-strong nuclear weapon state, like the US for example, might find itself tested trying to project conventional power against a strong regional state, close to that state’s home territory.

The concept of sole purpose has purchase in Australia precisely because for much of the nuclear age we have lived a long way from conventional front lines. We came to see extended nuclear deterrence as the deterrence of a remote scenario—an actual nuclear attack upon Australia. I don’t believe any Australian minister ever actually said that we thought it should apply only in such a scenario, but in practice that’s where we thought it most relevant. Most US allies lived close to serious threats, and didn’t have the luxury of thinking about extended nuclear deterrence applying in such limited circumstances. The question for Australia now, as it thinks about the sole-purpose issue, is whether our security blanket of distance is likely to be as effective in the future as it has been in the past.

The previous Labor government gave muted support to the notion of sole purpose. My own view is that persuading our ally to move towards such a declaration isn’t in our interests. Given that we live in a nuclear age, and that the spread of such weapons is still more likely than not, we should be thinking about ways that nuclear weapons can make a positive contribution to international security: capping large-scale conflict, regardless of whether it involves conventional or nuclear attack; strengthening the credibility of positive assurances to allies and partners in order to deter proliferation; and ensuring that nuclear deterrence plays just as effective a role in the Asian century as it did in the European one.

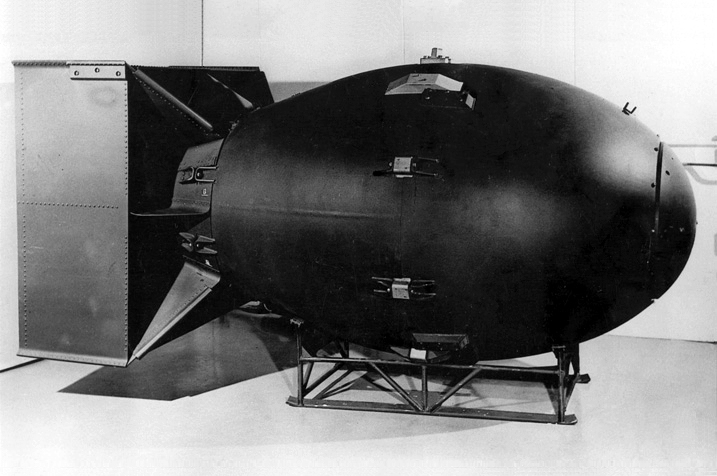

Rod Lyon is a fellow at ASPI and executive editor of The Strategist. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.