Russell Hunter and Victor Lal’s reflection on the implications of the election on Australia’s relations with Fiji raises more questions than it answers.

Russell Hunter and Victor Lal’s reflection on the implications of the election on Australia’s relations with Fiji raises more questions than it answers.

The orthodox view since the military coup in December 2006 has been that the hard line would lead to compromise on the part of the Fijian Government. The concern now is that compromise will mean selling out; that compromise means ‘Australia is helping Bainimarama entrench himself as dictator for life’. This is a concern, but not an outcome that Australian policymakers have countenanced . It’s a claim that needs to be fleshed out.

The first and most salient point that should frame discussion is that Australian led sanctions and diplomatic isolation haven’t led to compromise from Suva. The greatest potential for sanctions to succeed in altering the behavior of the target is during the tense period of diplomacy when they’re first threatened. Either the threat is seen as credible enough to modify behavior or the target accepts the costs of non-compliance. Once sanctions are imposed, the sender has already failed in influencing behavior through a credible threat.

In practice, once sanctions have been imposed they must influence compliance within a reasonable time, or they need to be either escalated or dropped. After previous coups in Fiji, sanctions quickly achieved results and/or were removed in short periods of time (under a year). The sanctions regime has been maintained despite failing to achieve its aims and no escalation options have been countenanced. Why would the incoming Abbott government expect to repeat the same policy prescriptions and have a different outcome?

Fiji has been willing to bear the costs, but over time the relative costs have diminished. In part this is because the sanctions regime didn’t include any elements that would target ordinary Fijians (such as trade sanctions). They were ‘smart sanctions’, targeting the military—who over time have worked around them. Direct flights have been negotiated with numerous countries. Military training, education and specialist medical care has been sourced elsewhere. Fiji isn’t cut off from international military cooperation, only cooperation with Australia and its allies.

Australian-led sanctions also isolated Fiji from regional and international organisations over which Canberra has influence, namely the Commonwealth and the Pacific Islands Forum (PIF). Fiji has also ignored these. It has developed the Pacific Small Islands Developing States (PSIDS) network through the UN system to face the world as a bloc which excludes Australia. It has sponsored the Pacific Islands Development Forum (PIDF) to push a green growth agenda around the PIF. It was elected Chair of the G77 plus China group at the UN this year after it was endorsed by the Asia and Pacific Islands Group. Fiji has shown no inclination to rejoin either the Commonwealth or PIF, unless on its terms. Why would the Abbott government continue to exclude Fiji from regional organisations and promote fractures in the regional architecture?

On a bilateral level, Australia was once Fiji’s closest partner. An unintended consequence of the longevity of sanctions is that Fiji has made new friends. Fiji’s ‘Look North (and West) strategy has seen a string of embassies open across the world. Fiji now has new friends in the Middle East, Southeast Asia and Northeast Asia (namely China). Many of these friends have resources and expertise. They have effectively filled the gaps left by Australia’s isolation.

Seven years of sanctions have failed to achieve Canberra’s stated aims (the swift restoration of democracy) and may have actually been counterproductive. So the pertinent question is: why would the Abbott government maintain a failed strategy?

This is an article about Australia’s foreign policy toward Fiji, not about Fiji’s domestic politics. These two issues may seem inseparable to many, but there’s an important distinction to be made. It may be in Australia’s interests to promote democracy in Fiji, but the present approach has failed to achieve this end. Could a thawing of relations and closer engagement reap rewards for Australia’s regional relations and democratisation?

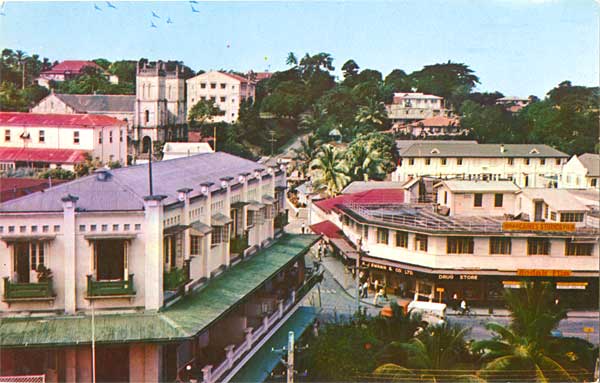

Michael O’Keefe is a senior lecturer in the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences at Latrobe University. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.