To watch the debate play out in America’s news media, it would seem that the opposite of ‘America First’ is American interventionism: a chronic penchant for leaping, to no apparent end, into wars of choice and demonstrating America’s unrivaled military power. But interventionism is not the same thing as internationalism. Conflating the two collapses the distinction between quick and decisive use of force and thoughtful engagement with the world and its problems.

In America’s ‘get ’er done’ transactional Weltanschauung, international disputes tend to be viewed as military challenges that are merely masquerading as political issues. In fact, they are usually the opposite, which is why the world’s most complex conflicts are rarely resolved by intervention.

Geopolitical conflicts have long, sordid histories and violence is more often a symptom of their intractability than an inherent trait. They often have something to do with identity and with claims of collective ownership of the land beneath the feet of a particular ‘nation’. The basis of political membership is usually more ethnic than civil, which is contrary to Americans’ understanding of nationhood.

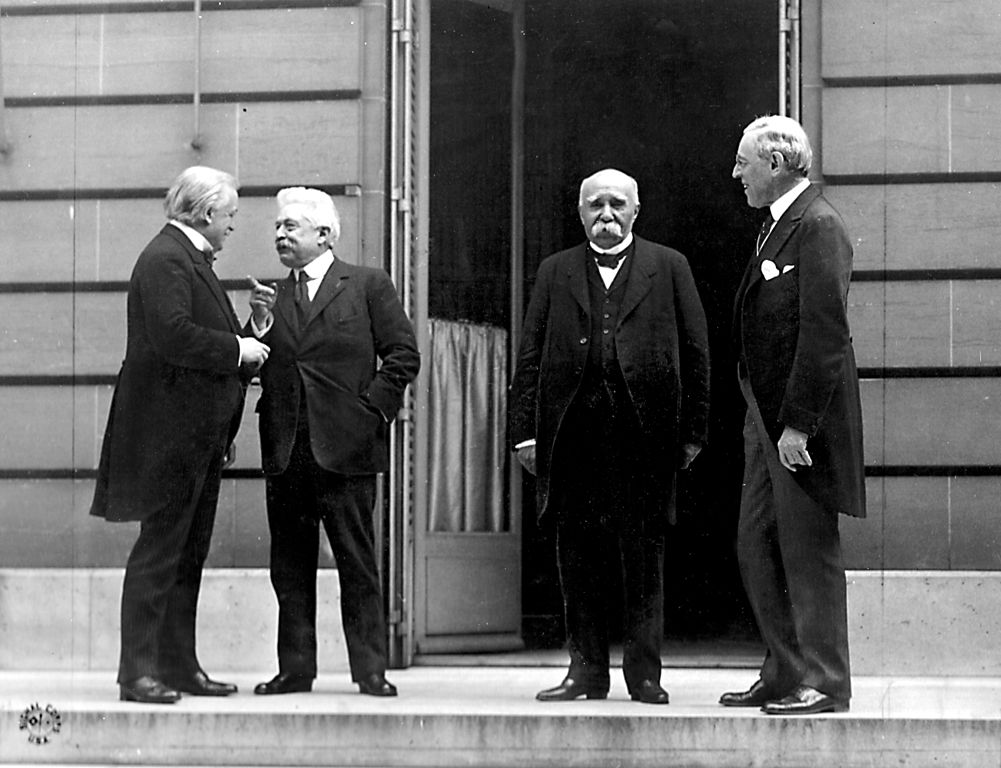

Moreover, contemporary problems can be the products of flawed arrangements that were made decades or even centuries ago. Two examples that immediately come to mind are the 1916 Sykes–Picot agreement between Britain and France, which carved up the Middle East, and the 1919 Treaty of Versailles, which established national borders in the Balkans. In both cases, creating new states may have seemed like a straightforward solution, but doing so turned out to be a prescription for more war.

For the United States, international conflicts are often an occasion to demonstrate ‘toughness’ and ‘resolve’. The US airstrikes in Bosnia were meant to lend momentum to a political process that already had the support of the European Union and Russia. The air campaign was a last resort, an effort to punish those who did not support the peace process.

For many American pundits and politicians, then, the lesson of Bosnia was merely that the bad guys should have been bombed sooner. Few took the opportunity to study the region’s complex history so that judicious inter-entity boundaries could be drawn up. If they had, the final arrangement might have done more to preserve external borders and nurture a constitutional structure that would allow the new state to be integrated into the European map.

Kosovo, too, supplied more historical complexity than many were willing to grapple with. On-the-ground diplomacy to achieve sovereign autonomy for Kosovo while respecting Serbs’ emotional connection to it was derided. The implication was that military means should be the first—rather than the last—option for securing Kosovo’s independence. Never mind that many European countries objected to the creation of an independent state and had called for multilateral diplomacy to be attempted before any discussion of air strikes.

Interventionism, with internationalism as an afterthought, continued after the turn of the century, but on a much bigger stage. After the attacks of 11 September 2001, the US led an invasion and subsequent occupation of Afghanistan to root out al-Qaeda. But after 17 years with troops on the ground in that country, Americans have lost patience, with many embracing US President Donald Trump’s ‘America First’ isolationism. In Iraq, where the connection to terrorism was more dubious, the US mounted a major military effort with goals that were perplexing and shifting, insofar as they were ever clearly articulated at all.

American interventionism has often been accompanied by criticism of friends and allies, who are depicted as weak and vacillating in the face of global challenges such as Russian President Vladimir Putin’s annexation of Crimea or China’s increasing assertiveness in the South China Sea. When things went wrong in Afghanistan and Iraq, the US blamed those countries’ political leaders, denouncing them as corrupt and deserving of regime change. The Europeans, too, were denounced, not just for fecklessness in the face of evil, but for living fat and happy lives without shouldering their proper burden.

With these narratives deeply etched into American public consciousness, it is no wonder that Trump’s dystopian vision has prevailed over internationalism, which has become a byword for the endless use of force and condescension towards allies.

American internationalism will be back at some point. But those who claim to support it could hasten its revival by acting in accordance with its original meaning. Traditional internationalists show respect for the opinions of others and a willingness to accept—and even champion—multilateral structures.

What internationalism needs now is a renewed American commitment to cooperation, even when other governments require more time to secure a mandate for action from their constituencies. At the end of the day, US international leadership must rest on American values and on a broad perception of adherence to the unalienable principles underlying liberal democracy. In other words, America must lead by example. Its failure to do so in recent times—not least on the refugee issue—has undermined the influence on which its power ultimately rests.