ASPI’s Mark Thomson in his report on this year’s defence budget has drawn our attention to the analysis by the US National Intelligence Council released early this year. The council foresees ‘deep shifts in the global landscape that portend a dark and difficult near future. The next five years will see rising tensions within and between countries.’ Further, ‘for better and worse, the emerging global landscape is drawing to a close an era of American dominance following the Cold War. So, too, perhaps is the rules-based international order that emerged after World War II.’

For us, more directly, what has changed since 1987 when we judged that the possibility of ‘escalated low level threats’ would have to determine much of today’s force structure? At that time our GDP was greater than ASEAN’s combined. Now Indonesia alone looks likely to pass us in the foreseeable future. In 1987, non-state actors posed little threat in our neighbouring states and to our sea lines of communication. Now a number of militant Islamist movements threaten governments.

Al-Qaeda includes sea-lane harassment among its ambitions. What are now ISIL affiliates use those waterways to commit acts of piracy. Regional armed forces, previously focused on internal security, are now acquiring force-projection capabilities. The unsettled maritime boundaries of our region, then latent in their impact, are now at the forefront of regional diplomacy.

The calculation beneath the immediate threat in 1987 was that our military capabilities could have to deal with a range of contingencies including ‘increased levels of air and sea harassment’ and air attacks on ‘northern settlements and offshore installations and territories’. Attacks on ‘shipping in proximate areas, mining of northern ports, and more frequent raids by land forces’ were also contemplated.

Over the past 30 years, regional military capabilities to conduct such operations have increased exponentially. Importantly, the calculation of intentions by state and non-state actors is immensely more complicated. The deadening effect on local delinquencies that the cautious Cold War superpowers sometimes exerted has largely disappeared.

We are now in warning time on a variety of fronts. The concept and its systematic force structure guidance has disappeared from our defence white papers. To be fair, pages 22 and 140 of DWP 2016 contain brief sections on managing greater preparedness and responding to strategic risk. There are also references to improving our defence infrastructure in relevant areas. We’ve been effectively engaged in multiple out-of-area activities since the 1987 DWP. That’s consumed official focus as well as resources. Further—much encouraged by us—our principal ally engaged with us and our local friends on security issues in our region more intensively in the last decade. It’s still so engaged, but with a more intensely unilateralist approach.

It’s clear that our problems are immediate. But our planning is not. The excellent capabilities outlined in the DWPs published from 2009 to 2016 are, in many cases, still decades away in planned commissioning of platforms. I’m likely to be dead by the time the first new submarine is accepted and will certainly be by the last. Fortunately, air capabilities are arriving earlier.

More than that we need a focus on the preparedness of the force in being. Those are the capabilities we’ll have for the next 10 years. We need to look at enhancing current platforms and keeping them in service longer. Note that as the US struggles towards a 350-ship navy, many platforms are as likely to be unmothballed as built. We also need to look to war stocks and essential supplies.

There’s a civilian component to this. If one was going to bring forward the 1987 vulnerabilities that are most immediate, one would look to sea lines and oil supplies. Our oil resources are well below international standards and, unlike in 1987, our refining capacity has almost disappeared. International Energy Agency rules say we should have 90 days’ worth of oil supplies. Uniquely among OECD countries, we are nowhere near that. (It has to be said, though, that getting there would be very expensive, with an unwanted load on petrol prices.) We feel secure because our supplies are in friendly Singapore or at sea between us. Singapore is not going to turn off the tap, but those sea lanes are something else.

Hardening vulnerable facilities as well as war stocks would be useful enhancements. Except for the oil issues, that would not be a major expense when compared with the cost of the new platforms. However, we would be running more quickly to the government’s stated target of 2% of GDP for defence spending. For all this to be acceptable, the political leadership in the first place, and then the public, would need to see with clarity the kinds of scenarios that the new capabilities were being acquired to deal with.

That type of planning has to be developed and provided by the government’s defence advisers. It was intensively developed in the 1980s. Its product and the underlying thinking were presented to the political leadership and the Australian people in the 1986 Dibb report and DWP ’87. The principal complaint then was that it was insufficiently ambitious. But even so we didn’t achieve the planned force levels. Now such assessments might well drive and enable a higher commitment.

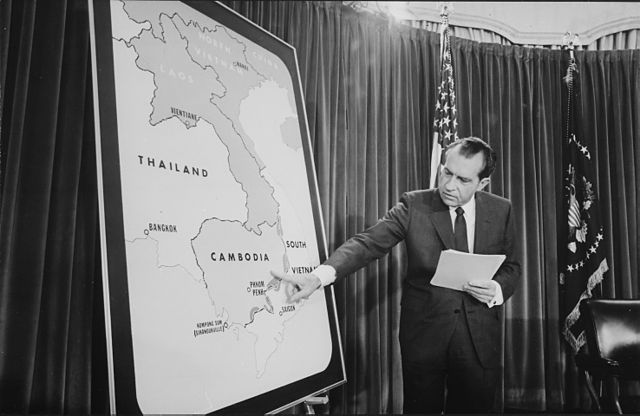

The US intelligence agencies have given us a warning as stark as we got from President Nixon on Guam in 1969. We’d better respond.