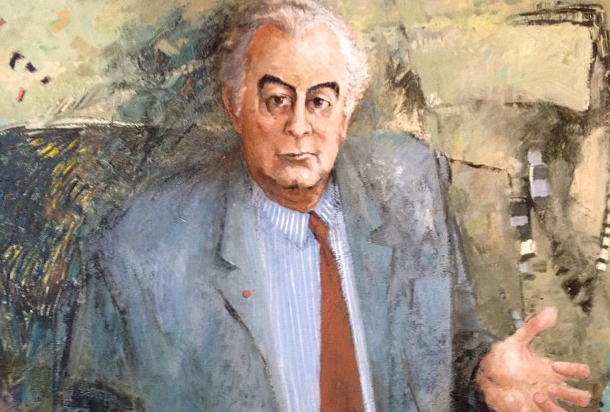

In memory of Gough Whitlam (1916–2014) and his contribution to Australian foreign policy, we republish here a brief excerpt from Ross Terrill’s ASPI Strategy paper, Facing the dragon, on Whitlam’s 1971 visit to China:

Zhou Enlai welcomed Whitlam to the East Chamber of the Great Hall of the People, with its leaping murals and crimson carpets. Present also were Chinese Foreign Minister Ji Pengfei and Trade Minister Bai Xiangguo. Zhou, a slight, handsome man with a theatrical manner, was all in grey except for a red ‘Serve the People’ badge, black socks inside his sandals, and black hair flecking the grey.

Whitlam gave Zhou a good account of Australia’s foreign policy, but showed little understanding of the impact of the split between Beijing and Moscow on Chinese and American thinking. The premier spent minutes criticising former US secretary of state John Foster Dulles for his policies of ‘encircling China’. He reached for his tea mug, sipped, and went on, ‘Today, Dulles has a successor in our northern neighbour’. Whitlam said ‘You mean Japan?’ Zhou was curt in response: ‘Japan is to the east of us—I said to the north’.

No doubt it was hard for a leader on the Australian left to accept that Mao’s Chinese Communist Party (CCP) might think of the Soviet Union as an enemy. In the exchanges about Dulles, the encircling of China and the Vietnam War, Whitlam unwisely volunteered that ‘The American people will never allow an American president to again send troops to another country’. Of course, they’ve done so numerous times since 1971, often without Chinese opposition.

If Zhou was tough on the Soviet Union, he was almost as tough on Japan. He feared that the Nixon Doctrine, asking for self-reliance on the part of US allies in Asia, would turn Japan into America’s ‘vanguard in East Asia’. He called it ‘the spirit of using Asians to fight Asians’ or, coining a new term, ‘using Austral-Asians to fight Asians’.

One of his strongest criticisms of Moscow, indeed, was its failure to oppose ‘Japanese militarism’. He feared that Japan would develop nuclear weapons. ‘Look at our so-called ally’, Zhou said to Whitlam of the Soviet Union. ‘They are in warm relations with the Sato government of Japan and also engaged in warm discussions on so-called ‘nuclear disarmament’ with the Nixon government, while China, their ally, is threatened by both of these.’

‘Is your own ally so very reliable?’ the Chinese premier challenged Whitlam. ‘They have succeeded in dragging you onto the Vietnam battlefield. How is that defensive? That is aggression.’ To his credit, Whitlam defended ANZUS. Later, Whitlam told me that he was surprised Zhou hadn’t attacked the American intelligence facilities in Australia. In fact, the omission was a sign that Mao was no longer as worried about the US as about the Soviet Union. However, the Chinese Foreign Minister did raise with Whitlam China’s unease that Australia had troops stationed in Singapore and Malaysia.

When the Labor leader expressed acceptance of the ‘One China’ principle that Beijing asked of foreign partners, the premier said crisply, ‘So far this is only words. When you return to Australia and become prime minister you will be able to carry out actions’.

And this reflection:

In December 1972, Prime Minister Whitlam, taking streamlined steps generally impossible in Washington, within a month of taking office reached agreement with Beijing on diplomatic relations, cut relations with Taiwan, and appointed the first Australian ambassador to the PRC. There were critics of the haste. Hugh Dunn (later the only Australian diplomat to be ambassador in both Taiwan and Beijing) was told by Chinese ambassador Huang Zhen, who negotiated with Australian ambassador Alan Renouf in Paris, that ‘Australia’s was the easiest’ of all negotiations over recognition he had handled. Observed Dunn, ‘The Chinese knew we wished to reach agreement quickly … one should never negotiate against a unilaterally self-imposed deadline’. Still, most Australians felt the step was overdue.

Ross Terrill is an associate of Harvard’s Fairbank Centre for Chinese Studies. Image courtesy of Flickr user Bobby Graham.