The Ukraine conflict has moved into uncharted territory as the EU and US spearhead maximum-damage sanctions against the Russian economy, while the Kremlin raises nuclear-readiness levels and launches rocket strikes against civilian targets in Ukrainian cities.

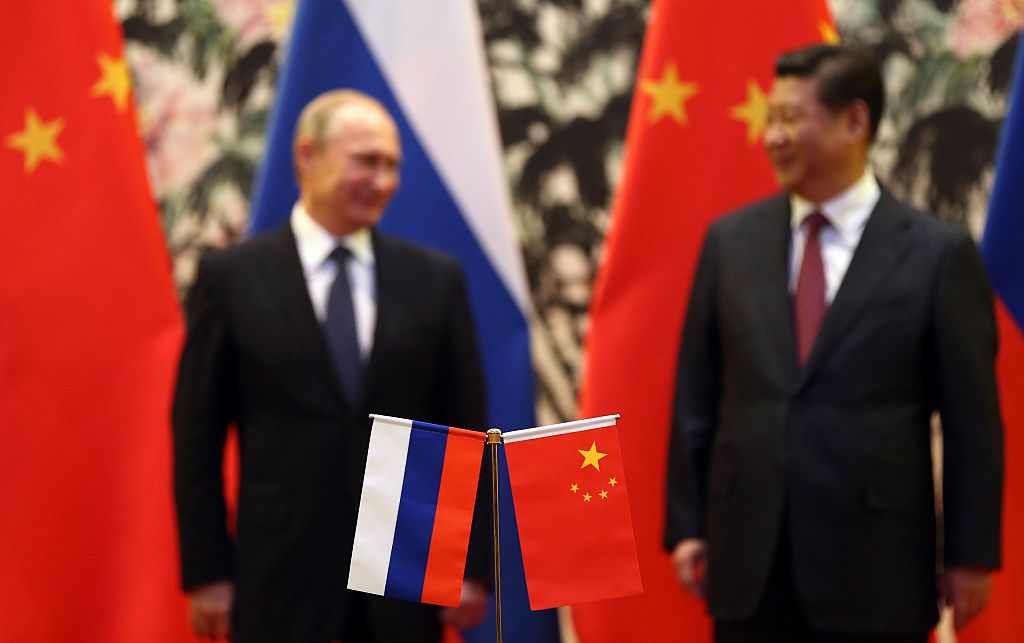

As the situation deteriorates, analysts in Washington and Brussels will parse China’s statements for clues as to what role it might play in the conflict, especially in light of the ‘no limits’ relationship announced by leaders Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin at the beginning of February.

Their 5,000-word statement expanded on the theme that Russia and China now share a fundamental worldview that is against the expansion of both NATO and liberal democracy. And yesterday, China’s foreign minister, Wang Yi, affirmed that the Russia–China partnership will endure and grow, ‘however precarious and challenging the international situation may be’.

Does this mean China will enable the Russian war effort? Will it try to use its relationship to persuade the Kremlin to de-escalate? Or will Xi attempt to distance China from the crisis as it gets uglier, waiting to see who retains the advantage? The nuanced opaqueness of China’s statements and actions since the invasion leaves open all three possibilities, at least in theory.

And that is precisely Beijing’s intention, said Chinese international relations professors Yang Cheng and Shi Yinhong in an interview with China’s Central News Agency. They said that on Ukraine, China was pursuing a delicate balance between its growing strategic and economic relationship with Russia on one hand and maintaining key economic relationships on the other. This understanding of China’s position as one of ‘pro-Russia neutrality’ is shared by many Western analysts.

Yang and Shi argue that China has conveyed its message to Russia in the nuances and that Putin will understand that China doesn’t necessarily approve of his actions but won’t intervene to stop him. Yang goes on to say that China believes its balancing act will get it through this crisis without damaging its relations with major Western markets.

Last week, US security officials shared intelligence with the New York Times indicating that the Chinese government was aware of Putin’s invasion plans, asked Russia not to proceed until after the Beijing Winter Olympics and said China wouldn’t interfere. It’s unclear at what level that dialogue took place.

But given the warm personal relationship between Xi and Putin, it’s highly unlikely that this was unknown to Xi, even if much of the Chinese government was caught unawares by the invasion. Again according to US intelligence, Chinese officials repeatedly rebuffed attempts by the Biden administration to share intelligence on Russia’s invasion plans, before briefing Russian counterparts on what they believed to be a piece of US information warfare.

It looks likely that Russia’s plans for Ukraine were very closely held in both Moscow and Beijing. According to reports from Russian journalists with Kremlin sources, many government officials there thought Putin merely intended to formally annex the territories it effectively took in 2014. It’s possible US intelligence knew more than the vast majority of senior officials in either country.

If Xi didn’t know, his ignorance would be embarrassing given China’s presumed closeness with Russia. But perhaps both he and Putin expected it to play out as it did with Russia’s occupation of Crimea and Donbas in 2014—low levels of resistance allowing a swift decapitation of Ukraine’s political apparatus, followed by more irksome but not disastrous sanctions and hand-wringing from the West which Russia would be prepared to ride out.

In other words, Xi might have thought that Western political systems, weakened in part by the hybrid warfare that Russia has been levelling against the West for over a decade, would be unable to respond effectively. Russia’s war would be another drain on the confidence of Western states and alliances, another defeat for democracy.

But Putin has triggered a very different scenario for which both countries seem much less prepared. Determined resistance in Ukraine and the swiftness with which NATO and global civil society have come together to isolate Russia economically and politically present new dilemmas for Beijing that will push its foreign policy beyond neat diplomatic formulas.

Is Xi now happy with the pace of geopolitical destabilisation that Russia—the junior partner on almost every metric save nuclear weapons—has now set? Does he really understand the scope of Putin’s ambitions and the significance of the line Russia just crossed by invading a European country with conventional military force backed with nuclear threats? How many geopolitical assumptions will need to be rethought? And what value does Russia have now as a strategic partner?

In the short term, Beijing will need to decide how, as Moscow’s closest strategic partner, it will handle Russia’s political and economic isolation, as international outrage and disgust at Putin’s invasion and continuing escalation of the war reaches fever pitch.

The UN Human Rights Council walkout In the middle of a speech by Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov, the overwhelming General Assembly vote against Russia and the World Bank and International Monetary Fund’s US$5.2 billion support package for Ukraine shows that Moscow has decisively lost the information war.

EU economic giants like Germany, so critical for the success of China’s Belt and Road Initiative, have already signalled that they want more from China than Russia-inflected neutrality. Just before the war began, German Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock warned that if China tolerates a Russian invasion of Ukraine, Berlin ‘cannot have normal relations’ with Beijing. And given the increased relevance of Baltic states to EU security, China’s attempts to bankrupt Lithuania over its relationship with Taiwan will appear in an even poorer light now.

There’s every indication that atrocities and nuclear tensions will escalate as Russia attempts to eliminate Ukraine’s civilian resistance and force a victory before sanctions affect the war effort. China’s failure to condemn Russia and its repeated calls for ‘diplomacy’ without any action make its attempts to project neutrality on the conflict extremely unconvincing—especially when it’s running a pro-Putin campaign so enthusiastically inside its borders.

Worryingly for China, the courage of Ukrainians fighting for their sovereignty provides a huge boost to pro-democracy forces everywhere. All over the globe, civil society—always a blind spot for authoritarians—has mobilised in support of Ukraine, as evidenced by the massive street protests and flood of support to refugees.

Entities as diverse as MI6, Europe’s classical music concert halls and the iconic 101 skyscraper in Taipei have displayed Ukraine’s flag, and a kind of spontaneous global citizens’ defence movement against the Putin regime is emerging. This includes hacker groups like Anonymous and members of what Bellingcat founder Eliot Higgins calls the global open-source intelligence community fighting back against Russian disinformation in real time, as well as ex-military personnel from across the world volunteering to fight.

In contrast, Russia’s trajectory towards an impoverished, unstable and isolated future dents the faux-populist pulling power of autocracies whose main attraction is the projection of national strength and stability in uncertain times. And an important diplomatic and strategic asset for Russia and China, Putin’s mystique as a geostrategic grandmaster, an avatar for aspiring dictators and autocrats, and a key strategic asset for Russia, may be fading because of his brutal Ukraine miscalculation.

Moscow’s propagandists will continue to reach out to admirers of authoritarianism in the EU and US. And Russia and China will try to counter reality by continuing to promote a narrative of Russia as a victim of Western aggression, particularly when sanctions hit Russian citizens, something that many in the international community feel justifiably uncomfortable about. But victimhood is a hard sell as Russian atrocities in Ukraine multiply.

All of this makes Russia diplomatic dead weight for China to the extent that it is trying reshape the global order in its own image. A key part of China’s strategy in international institutions has been to try to capitalise on perceptions of political instability in the US, especially when Donald Trump was president, and the resulting alliance fractures to position Russia and China as the stronger and more durable great powers. But influencing the international order is much harder when your main ally has become a complete pariah not only in diplomatic institutions, but in the sporting and cultural realms as well. In pursuing its own geopolitical ambitions, China can ill afford to be pulled into Russia’s reputational black hole.