Being Australia’s foreign minister and then defence minister over six years gave Stephen Smith an opportunity to see changes coming in the region, and to assess the risks and opportunities they’d bring.

Now high commissioner to the UK after co-authoring the 2023 defence strategic review, Smith was foreign minister from 2007 to 2010 and defence minister from 2010 to 2013.

In a video interview as part of ASPI’s ‘Lessons in leadership’ series, he tells former ASPI executive director Peter Jennings he’s proud of being the first minister to put into an official document the notion of the Indo-Pacific and reaching out to India, Indonesia and other countries to set the scene for it.

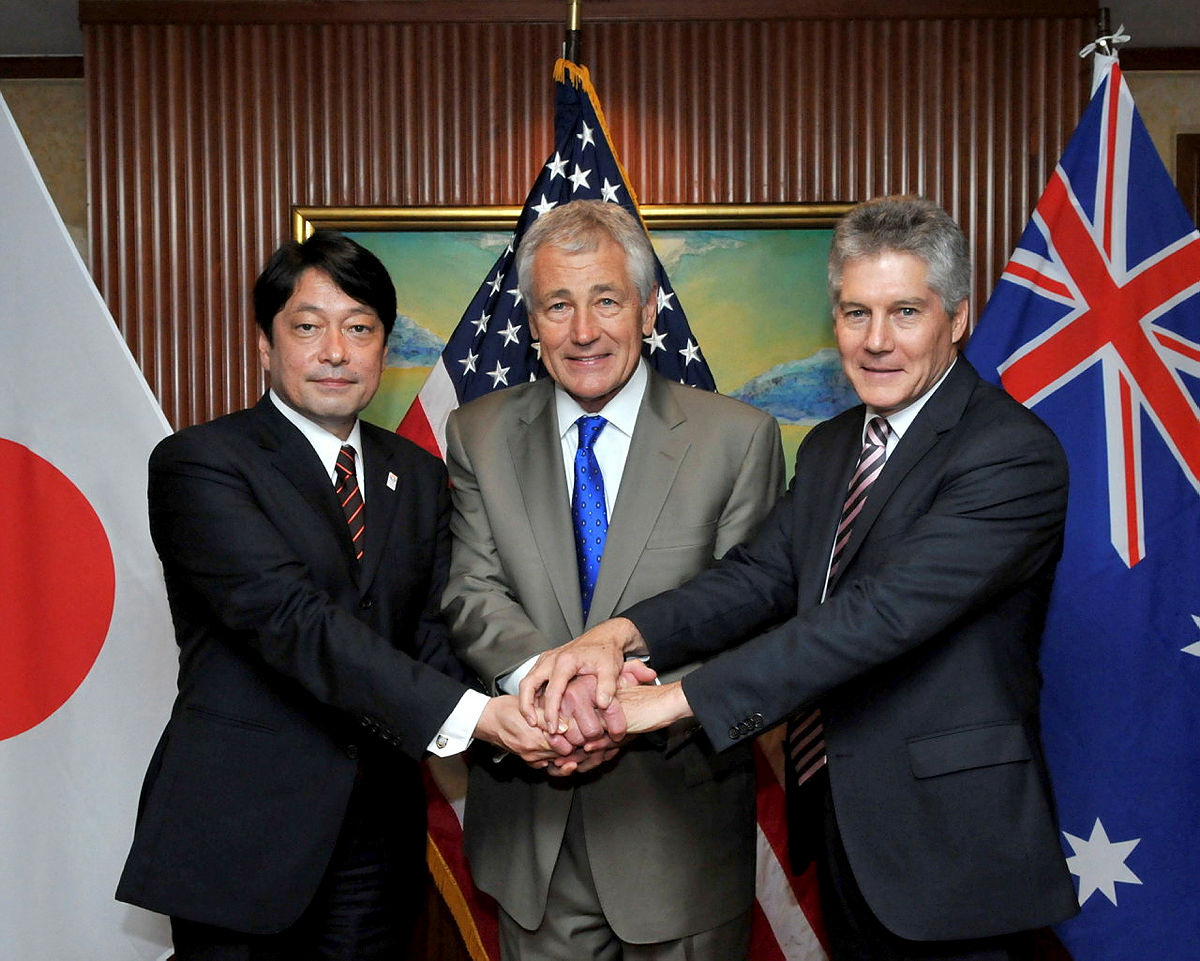

Smith attended six AUSMIN meetings, as foreign and defence minister. During his time at those high-level US-Australia consultations there were significant practical developments in the alliance that included, ultimately, the annual rotational presence of 2500 US marines in Darwin and the increased use of Australian bases by the US Air Force.

Smith says his strategic thinking evolved during his time as foreign minister and crystalised as defence minister. ‘We were living in a changing world, that the world was not just going to be about China and the US, and the extent to which that relationship was managed or not managed.’

Big geopolitical and geo-economic things were occurring with the rise of India and Indonesia as global influences. ‘In the blink of an eye, India would be the second or third largest economy, Indonesia, the fourth largest economy, so things were happening on our patch.’

Other ASEAN tigers, such as Vietnam, were on the move. ‘So, I came to the notion that we had to start looking at what we came to describe as the Indo-Pacific, and that culminated with the defence white paper in 2013, where for the first time, the notion of the Indo-Pacific was introduced into Australian strategic affairs.’ That continued with the Coalition’s 2017 foreign policy white paper and successive defence white papers.

‘At the time, we tried to argue, not just to the US, but to India, Japan, other countries, that this was a notion we should adopt.’ That was a struggle at the time, says Smith but now it seems everyone has taken on the concept—ASEAN, India, Japan the EU, France, Germany, and the UK.

‘We cracked that strategic notion which forced us to say, okay, when we look at our part of the world, it can’t just be the South Pacific. It also has to be what’s occurring in our northern and western approaches.’

The focus was on both prosperity and security.

The Australia-China relationship was very different a decade ago and the impression left by Xi Jinping when he came to Australia in 2014 was of China as a responsible stakeholder. ‘I think it’s all too easy to look back at those days with what we know now,’ Smith says.

The relationship changed dramatically as China became much more assertive and aggressive about the South China Sea and Hong Kong, and in its treatment of its Uyghur minority.

Australia’s biggest project now had to be diversification of its trade and economy and, on the security front, interweaving alliance relationships with nations such as India, Indonesia and Vietnam.

‘I brought the Vietnamese defence minister to Australia for the first time to try and grow our relationship with Vietnam,’ says Smith. Australia had a history with that country of 100 million people. ‘They perversely regard us well and they’re going to be an ASEAN tiger, so we need to grow both economically and strategically with them as well.’

The Americans were doing a global force posture review, so Smith asked Defence ‘where’s ours?’ The results fed into the 2013 white paper. The Australians had a very strong view that they had to keep the US engaged in this part of the world to ensure that the prosperity and security since World War II continued. The US was considering pivoting some if its resources from the Atlantic and Europe to support its hub-and-spoke alliance relationships in the Pacific.

Then followed long and detailed conversations to encourage the US to enhance its operational measures in this region to reflect the notion of the Indo-Pacific on the rise. Eventually, that resulted in the marines rotations in Darwin, greater US utilisation of RAAF ‘bare bases’ in the north and a plan for a US and UK nuclear-powered submarine presence in Western Australia’s HMAS Stirling naval base.

Smith and Dennis Richardson, who was Defence Department secretary after being secretary of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, worked on this for a long time with Hillary Clinton, Leon Panetta and Kurt Campbell. They had to persuade the Americans that this had to be done on Australian terms.

‘I had any number of conversations where I was saying, “we don’t have US bases in Australia, we have joint facilities, and if we’re going to do this, it’s got to be done on a rotational basis, which is fit for purpose”,’ says Smith.

‘That took a bit of effort with the Americans, but to his credit, when it was all over, Kurt Campbell came to me and said: “that went very well. You were right, we were wrong”.’

Smith recalls having to increase ADF capability with a reduced budget after the Global Financial Crisis when he was both the defence minister who oversaw the 2013 defence white paper and a member of Cabinet’s Expenditure Review Committee.

He was aware that Defence would be targeted for funding cuts and concluded that if he and Defence leaders were left alone to manage that situation they’d be able to protect the things that needed protecting.

‘The last thing I wanted was Treasury and Finance trampling all over Defence in a reducing budget environment.’ On the advice of Smith’s predecessor, John Faulkner, they ‘ring fenced’ operations in Afghanistan and prioritised the most urgently needed capabilities including doubling the RAAF’s fleet of massive C-17 transport aircraft and acquiring Super Hornets and Growler electronic attack aircraft.

The Navy got its air warfare destroyers and landing ships, which were ordered by the previous government, and replacement supply ships, and frigate upgrades continued. There was a dramatic improvement in sustainment of the Collins class submarines that saw an increase in availability from no boats or one boat to four of the six. That was world class for a submarine fleet.

Smith made three trips to Sweden to lock up the intellectual property for the Swedish-designed submarines with a view to ultimately replacing them with an evolved version, a ‘son or daughter of Collins’. ‘It was of some surprise to me that that option was effectively excluded from the subsequent government’s consideration of future submarines,’ he says.

He and Richardson set the scene for what is now the Australian Signals Directorate to be a statutory authority in its own right under the Defence portfolio. ‘I was very pleased with the way in which we made our commitment in Afghanistan, made our contribution, and then essentially got out with dignity.’ That allowed Australia to grow its relationship with NATO and the European Union.

Smith says being minister of foreign affairs and defence, and a member of the National Security Committee of Cabinet changed his life. ‘I didn’t envisage that when I entered parliament. I didn’t envisage it when I entered the ministry. But, as you can see from the backdrop, it’s something that I carry with me for the rest of my academic career and life generally.’

‘There are not many colleagues who you can go to. You can go to your predecessors, you can go to the foreign minister, but there’s not a wide circle of confidants you can have, as you can have in a domestic portfolio.’

Smith says the same is true in a sense of foreign affairs. ‘But foreign affairs is overall an easier portfolio in terms of the things that you have to deal with. Sure, you have the occasional consular crisis and people are in trouble overseas, but they’re in a sense intermittent. The overriding thing about Defence is it’s ever present, and it’s always different and difficult.’

He recalls Labor appointing former coalition defence minister Brendan Nelson ambassador to NATO. ‘That was very important,’ says Smith. ‘He was very good, his defence experience helped us a lot in terms of what we were doing in NATO.’

Smith says senior Defence officials understood the difficulties an incoming minister would confront. In the covering letter to him with the incoming government brief they said: ‘Minister, there will be surprises. minister, we will let you down. Minister, there will be times when it’s very difficult’.

There were terrible capability failures for whom no one ever seemed to be accountable. But it was not as though someone was trying to ‘stuff them up’. Everyone had the best of intentions. ‘It’s just the different silos, the different perspectives, and putting a big unwieldy beast into a manageable compartment. They tend to be the issues.’

Asked what advice he’d give a new defence minister, Smith says: ‘You should speak to all of your predecessors because they’ll all have a conversation with you, and you should just learn from them some of the challenges that you’re going to have—and there are some early lessons to be learned. ‘You’ve got to be assiduous. You have to be fastidious. It’ll take over your life for the period of time, but you also have to be clear sighted. Don’t let the volume of detail get in the way of the strategic outcome that’s required here? What are the things that we need to do?’

If a new minister arrives with five things written on the palm of their hand and gets three of them done, they’ve done well, says Smith.

‘Best advice I can give is that you’ve got to go into it with your eyes open. There is a comradery, which, if you’re a member of the former defence minister’s club, can be very helpful to future ministers.’

‘You need to understand, there’ll be surprises, you will be let down, but you’ve just got to work through those issues and get to the strategic outcomes that protect and defend our national interests.’

ASPI’s ‘Lessons in leadership’ series is produced with the support of Lockheed Martin Australia.