As the Australia–Japan security relationship continues to strengthen, there’s concern among the South Korean security community that that may come at the expense of their country’s own interests.

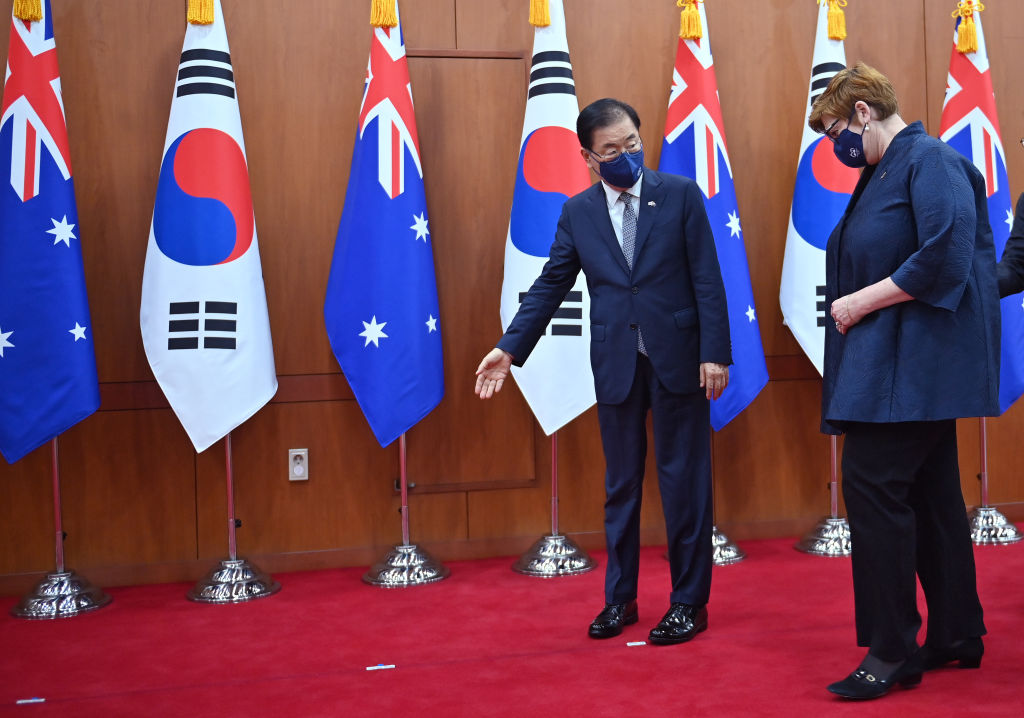

Security cooperation between South Korea and Australia has become closer over the past decade, reflected in the holding of joint maritime military exercise Haedori–Wallaby since 2012 and the biennial 2+2 meeting of foreign and defence ministers since 2013. Australia has also occasionally participated in the US–Korea amphibious exercise SsangYong, the anti-biological warfare exercise Able Response, and the Ulchi Freedom Guardian exercise.

The speed with which security cooperation has been developing between South Korea and Australia, however, doesn’t match the development of cooperation between Australia and Japan. The security relationship between Australia and Japan has been enhanced to the point that they’re often called ‘quasi allies’. Consequently, there’s a view in Seoul that Canberra is more supportive of Japan’s security posture than of Korea’s.

Concerns peaked after Australian prime minister Tony Abbott remarked in October 2013 that Japan was ‘Australia’s best friend in Asia’. Then, the conservative government in Seoul had assessed that the North Korean regime would soon collapse. South Korea hoped to rule out any possibility that Japan would interfere if a contingency should arise on the peninsula. South Korean concerns about any such intervention were founded on the United Nations Korea Command—Rear being located in Japan.

This gives the UN HQ legal grounds to dispatch UN troops from Japan to Korea in the event of a Korean contingency. Another (mis)perception in South Korea that has hindered security cooperation between Seoul and Canberra has been Australian support for the efforts of the US and Japan to construct a missile-defence system in the region.

In 2017, tensions heightened between Pyongyang and Washington when North Korea threatened to test-fire an intercontinental ballistic missile towards the US mainland. Australia’s prime minister Malcolm Turnbull announced that Australia would invoke its alliance treaty to defend the US if that eventuated.

Australia’s position wasn’t appreciated by the South Korean government, which saw these remarks as escalatory and unnecessarily provocative eye-for-an-eye exchanges. It feared that they’d damage South Korea’s efforts to mitigate tension between North Korea and the US.

In 2020, Japan and Australia agreed to sign a reciprocal access agreement, a bilateral arrangement that would enable Australia to dispatch a large number of military personnel to Japan for exercises on Japanese soil.

By 2021, Japan had enhanced its role as a key node of the US-led security network in East Asia and beyond. It achieved this by enhancing its security cooperation with Great Britain and France, and in May conducted a military exercise in Japan with France, the US and Australia.

Given the already very close security relationship between Japan and Australia, some in the South Korean security elite are concerned that their enhanced, and expanding, security cooperation as part of the US-led network might result in Japan emerging as a regional hub of that alliance network.

While South Korea has expanded its security cooperation in the region and has joined various multilateral military exercises in the Pacific and Indian Oceans with different groups of states, it has two major concerns.

South Korea doesn’t feel comfortable with Japan taking a central role in exercises in the East Sea or Northeast Asia and remains concerned about its diminished security status and the possibility of being ‘demoted’ in relation to Japan in the northern axis of the US-led security network.

South Korea also remains concerned that participation in such exercises would risk unnecessarily provoking China, complicating cooperation between Seoul and Beijing on North Korea.

If Australia were perceived by South Korea as becoming too deeply engaged in security cooperation with Japan, it would again raise suspicion that Australia is more supportive of Japan than of South Korea.

To maintain its position within the US-led security network, South Korea needs to be more active in joining military exercises organised by the US. One way to enhance the Korea–Australia bilateral relationship would be for Korea to join the Australia-led exercises in the Pacific along with the US, rather than the Japan-led exercises in Northeast Asia.

In this context, it’s worth noting South Korea’s participation in the Talisman Sabre military exercise involving Australia and the US in 2021. While, strategically, Korea has been hesitant to join military exercises that might be seen as targeting China, it has good reasons to participate in them from an operational perspective, especially to enhance interoperability.

As it seeks to enhance its security cooperation with Australia, whether bilaterally or more broadly, South Korea must walk a fine line.